Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New World porcupines of the family Erethizontidae. Both families belong to the infraorder Hystricognathi within the profoundly diverse order Rodentia and display superficially similar coats of rigid or semi-rigid quills, which are modified hairs composed of keratin. Despite this, the two groups are distinct from one another and are not closely related to each other within the Hystricognathi. The largest species of porcupine is the third-largest living rodent in the world, after the capybara and beaver.

The New World porcupines, family Erethizontidae, are large arboreal rodents, distinguished by their spiny coverings from which they take their name. They inhabit forests and wooded regions across North America, and into northern South America. Although both the New World and Old World porcupine families belong to the Hystricognathi branch of the vast order Rodentia, they are quite different and are not closely related.

The Old World porcupines, or Hystricidae, are large terrestrial rodents, distinguished by the spiny covering from which they take their name. They range over the south of Europe and the Levant, most of Africa, India, and Southeast Asia as far east as Flores. Although both the Old World and New World porcupine families belong to the infraorder Hystricognathi of the vast order Rodentia, they are quite different and are not particularly closely related.

The serval is a wild cat native to Africa. It is widespread in sub-Saharan countries, except rainforest regions. Across its range, it occurs in protected areas, and hunting it is either prohibited or regulated in range countries.

The honey badger, also known as the ratel, is a mammal widely distributed in Africa, Southwest Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Because of its wide range and occurrence in a variety of habitats, it is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

The South African springhare is a medium-sized terrestrial and burrowing rodent. Despite the name, it is not a hare. It is one of two extant species in the genus Pedetes, and is native to southern Africa. Formerly, the genus was considered monotypic and the East African springhare was included in P. capensis.

The North American porcupine, also known as the Canadian porcupine, is a large quill-covered rodent in the New World porcupine family. It is the second largest rodent in North America, after the North American beaver. The porcupine is a caviomorph rodent whose ancestors crossed the Atlantic from Africa to Brazil 30 million years ago, and then migrated to North America during the Great American Interchange after the Isthmus of Panama rose 3 million years ago.

The Indian crested porcupine is a hystricomorph rodent species native to southern Asia and the Middle East. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. It belongs to the Old World porcupine family, Hystricidae.

The greater cane rat, also known as the grasscutter, is one of two species of cane rats, a small family of African hystricognath rodents. It lives by reed-beds and riverbanks in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The bristle-spined rat is an arboreal rodent from the Atlantic forest in eastern Brazil. Also known as the bristle-spined porcupine or thin-spined porcupine, it is the only member of the genus Chaetomys and the subfamily Chaetomyinae. It was officially described in 1818, but rarely sighted since, until December 1986, when two specimens - one a pregnant female - were found in the vicinity of Valencia in Bahia. Since then it has been recorded at several localities in eastern Brazil, from Sergipe to Espírito Santo, but it remains rare and threatened due to habitat loss, poaching and roadkills.

Hystrix is a genus of porcupines containing most of the Old World porcupines. Fossils belonging to the genus date back to the late Miocene of Africa.

The crested porcupine, also known as the African crested porcupine, is a species of rodent in the family Hystricidae native to Italy, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa.

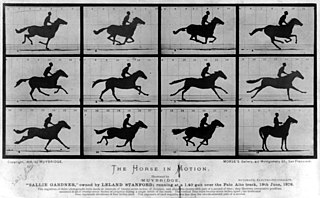

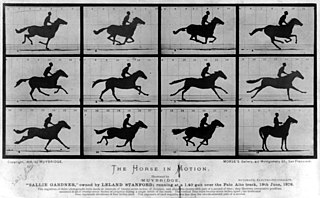

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance. "Cursorial" is often used to categorize a certain locomotor mode, which is helpful for biologists who examine behaviors of different animals and the way they move in their environment. Cursorial adaptations can be identified by morphological characteristics, physiological characteristics, maximum speed, and how often running is used in life. There is much debate over how to define a cursorial animal specifically. The most accepted definitions include that a cursorial organism could be considered adapted to long-distance running at high speeds or has the ability to accelerate quickly over short distances. Among vertebrates, animals under 1 kg of mass are rarely considered cursorial, and cursorial behaviors and morphology is thought to only occur at relatively large body masses in mammals. There are a few mammals that have been termed "micro-cursors" that are less than 1 kg in mass and have the ability to run faster than other small animals of similar sizes.

The giant forest hog, the only member of its genus (Hylochoerus), is native to wooded habitats in Africa and is generally considered the largest wild member of the pig family, Suidae; however, a few subspecies of the wild boar can reach an even larger size. Despite its large size and relatively wide distribution, it was first described only in 1904. The specific name honours Richard Meinertzhagen, who shot the type specimen in Kenya and had it shipped to the Natural History Museum in England.

The wildlife of Iraq includes its flora and fauna and their natural habitats. Iraq has multiple biomes from mountainous region in the north to the wet marshlands along the Euphrates river. The western part of the country is mainly desert and some semi-arid regions. As of 2001, seven of Iraq's mammal species and 12 of its bird species were endangered. The endangered species include the northern bald ibis and Persian fallow deer. The Syrian wild ass is extinct, and the Saudi Arabian dorcas gazelle was declared extinct in 2008.

In a zoological context, spines are hard, needle-like anatomical structures found in both vertebrate and invertebrate species. The spines of most spiny mammals are modified hairs, with a spongy center covered in a thick, hard layer of keratin and a sharp, sometimes barbed tip.

The Cape dune mole-rat is a species of solitary burrowing rodent in the family Bathyergidae. It is endemic to South Africa and named for the Cape of Good Hope.

The Malayan porcupine or Himalayan porcupine is a species of rodent in the family Hystricidae. Three subspecies are extant in South and Southeast Asia.