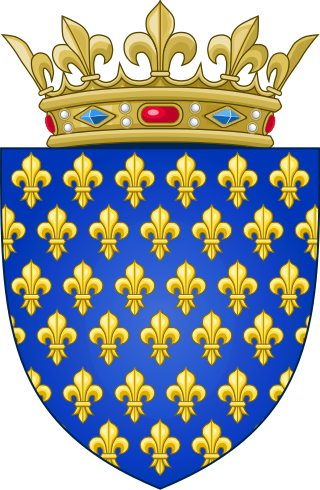

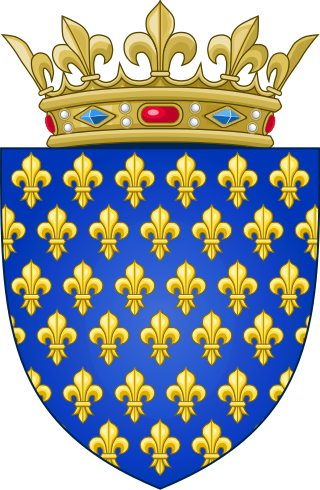

The Capetian dynasty, also known as the "House of France", is a dynasty of European origin, and a branch of the Robertians and the Karlings. It is among the largest and oldest royal houses in Europe and the world, and consists of Hugh Capet, the founder of the dynasty, and his male-line descendants, who ruled in France without interruption from 987 to 1792, and again from 1814 to 1848. The senior line ruled in France as the House of Capet from the election of Hugh Capet in 987 until the death of Charles IV in 1328. That line was succeeded by cadet branches, the Houses of Valois and then Bourbon, which ruled without interruption until the French Revolution abolished the monarchy in 1792. The Bourbons were restored in 1814 in the aftermath of Napoleon's defeat, but had to vacate the throne again in 1830 in favor of the last Capetian monarch of France, Louis Philippe I, who belonged to the House of Orléans. Cadet branches of the Capetian House of Bourbon are still reigning over Spain and Luxembourg.

The House of Bourbon is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. A branch descended from the French Bourbons came to rule Spain in the 18th century and is the current Spanish royal family. Further branches, descended from the Spanish Bourbons, held thrones in Naples, Sicily, and Parma. Today, Spain and Luxembourg have monarchs of the House of Bourbon. The royal Bourbons originated in 1272, when Robert, the youngest son of King Louis IX of France, married the heiress of the lordship of Bourbon. The house continued for three centuries as a cadet branch, serving as nobles under the direct Capetian and Valois kings.

The Capetian house of Valois was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the family founded cadet branches in Orléans, Anjou, Burgundy, and Alençon.

An appanage, or apanage, is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a monarch, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much of Europe.

Duke of Burgundy was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by the French crown in 1477, and later by members of the House of Habsburg, including Holy Roman emperors and kings of Spain, who claimed Burgundy proper and ruled the Burgundian Netherlands.

Duke of Bourbon is a title in the peerage of France. It was created in the first half of the 14th century for the eldest son of Robert of France, Count of Clermont, and Beatrice of Burgundy, heiress of the lordship of Bourbon. In 1416, with the death of John of Valois, the Dukes of Bourbon were simultaneously Dukes of Auvergne.

Charles of Valois, the fourth son of King Philip III of France and Isabella of Aragon, was a member of the House of Capet and founder of the House of Valois, whose rule over France would start in 1328.

The House of Capet ruled the Kingdom of France from 987 to 1328. It was the most senior line of the Capetian dynasty – itself a derivative dynasty from the Robertians.

A cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons (cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets have historically been passed from a father to his firstborn son in what is known as primogeniture; younger sons, the cadets, inherited less wealth and authority to pass on to future generations of descendants.

The House of Courtenay is a medieval noble house, with branches in France, England and the Holy Land. One branch of the Courtenays became a royal house of the Capetian dynasty, cousins of the Bourbons and the Valois, and achieved the title of Latin Emperor of Constantinople.

Catherine I, also Catherine of Courtenay, was the recognised Latin Empress of Constantinople from 1283 to 1307, although she lived in exile and only held authority over Crusader States in Greece. In 1301, she became the second wife of Charles of Valois, by whom she had one son and three daughters; the eldest of these, Catherine II of Valois, Princess of Achaea succeeded her as titular empress.

Peter I of Courtenay was the sixth son of Louis VI of France and his second wife, Adélaide de Maurienne. He was the father of the Latin Emperor Peter II of Courtenay.

The Capetian House of Anjou, or House of Anjou-Sicily, or House of Anjou-Naples was a royal house and cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. It is one of three separate royal houses referred to as Angevin, meaning "from Anjou" in France. Founded by Charles I of Anjou, the youngest son of Louis VIII of France, the Capetian king first ruled the Kingdom of Sicily during the 13th century. The War of the Sicilian Vespers later forced him out of the island of Sicily, which left him with the southern half of the Italian Peninsula, the Kingdom of Naples. The house and its various branches would go on to influence much of the history of Southern and Central Europe during the Middle Ages until it became extinct in 1435.

The House of Valois-Burgundy, or the Younger House of Burgundy, was a noble French family deriving from the royal House of Valois. It is distinct from the Capetian House of Burgundy, descendants of King Robert II of France, though both houses stem from the Capetian dynasty. They ruled the Duchy of Burgundy from 1363 to 1482 and later came to rule vast lands including Artois, Flanders, Luxembourg, Hainault, the county palatine of Burgundy (Franche-Comté), and other lands through marriage, forming what is now known as the Burgundian State.

A prince du sang or prince of the blood is a person legitimately descended in male line from a sovereign. The female equivalent is princess of the blood, being applied to the daughter of a prince of the blood. The most prominent examples include members of the French royal line, but the term prince of the blood has been used in other families more generally, for example among the British royal family and when referring to the Shinnōke in Japan.

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or domaine royal of France were the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France. While the term eventually came to refer to a territorial unit, the royal domain originally referred to the network of "castles, villages and estates, forests, towns, religious houses and bishoprics, and the rights of justice, tolls and taxes" effectively held by the king or under his domination. In terms of territory, before the reign of Henry IV, the domaine royal did not encompass the entirety of the territory of the kingdom of France and for much of the Middle Ages significant portions of the kingdom were the direct possessions of other feudal lords.

The House of Dampierre played an important role during the Middle Ages. Named after Dampierre, in the Champagne region, where members first became prominent, members of the family were later Count of Flanders, Count of Nevers, Counts and Dukes of Rethel, Count of Artois and Count of Franche-Comté.

Succession to the French throne covers the mechanism by which the French crown passed from the establishment of the Frankish Kingdom in 486 to the fall of the Second French Empire in 1870.

Peter of Courtenay (French: Pierre de Courtenay was a French knight and a member of the Capetian House of Courtenay, a cadet line of the royal House of Capet. From 1239 until his death, he was the ruling Lord of Conches and Mehun-sur-Yèvre.

Robert of Courtenay, born was lord of Champignelles and grandson of Louis VI of France. Robert de Courtenay was the seventh child of ten children of Peter I of Courtenay and his wife, Elizabeth de Courtenay. Robert took part in the conquest of Normandy in 1204. During the siege of Château Gaillard, he fought alongside his cousin Philip II of France. In 1228, he left for a crusade to the Holy Land, where he died eleven years later in Palestine.