Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through the constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Reporters Without Borders is an international non-profit and non-governmental organization focused on safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its advocacy as founded on the belief that everyone requires access to the news and information, in line with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that recognises the right to receive and share information regardless of frontiers, along with other international rights charters. RSF has consultative status at the United Nations, UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and the International Organisation of the Francophonie.

Turkmenistan's human rights record has been heavily criticized by various countries and scholars worldwide. Standards in education and health declined markedly during the rule of President Saparmurat Niyazov.

The mass media in Georgia refers to mass media outlets based in the Republic of Georgia. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. The Constitution of Georgia guarantees freedom of speech. Georgia is the only country in its immediate neighborhood where the press is not deemed unfree. As a country in transition, the Georgian media system is under transformation.

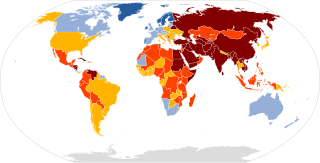

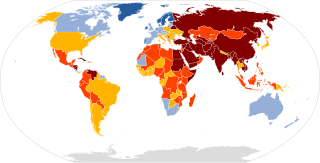

The World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) is an annual ranking of countries compiled and published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) since 2002 based upon the organization's own assessment of the countries' press freedom records in the previous year. It intends to reflect the degree of freedom that journalists, news organizations, and netizens have in each country, and the efforts made by authorities to respect this freedom. Reporters Without Borders is careful to note that the WPFI only deals with press freedom and does not measure the quality of journalism in the countries it assesses, nor does it look at human rights violations in general.

The working conditions of journalists in Algeria have evolved since the 1962 independence. After 1990, the Code of Press was suppressed, allowing for greater freedom of press. However, with the civil war in the 1990s, more than 70 journalists were assassinated by terrorists. Sixty journalists were killed between 1993 and 1998 in Algeria.

There are over ten different languages in the Israeli media, with Hebrew as the predominant one. Press in Arabic caters to the Arab citizens of Israel, with readers from areas including those governed by the Palestinian National Authority. During the eighties and nineties, the Israeli press underwent a process of significant change as the media gradually came to be controlled by a limited number of organizations, whereas the papers published by political parties began to disappear. Today, three large, privately owned conglomerates based in Tel Aviv dominate the mass media in Israel.

North Korea ranks among some of the most extreme censorship in the world, with the government able to take strict control over communications. North Korea sits at the bottom of Reporters Without Borders' 2023 Press Freedom Index, ranking 180 out of the 180 countries investigated.

Aleksandar Vučić is a Serbian politician serving as the president of Serbia since 2017. A member of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), he previously served as the president of the SNS from 2012 to 2023, first deputy prime minister from 2012 to 2014, and prime minister of Serbia from 2014 to 2017.

The mass media in Croatia refers to mass media outlets based in Croatia. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. The Constitution of Croatia guarantees freedom of speech and Croatia ranked 63rd in the 2016 Press Freedom Index report compiled by Reporters Without Borders, falling by 5 places compared to the 2015 Index.

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments, private institutions, and other controlling bodies.

Ukraine was in 96th place out of 180 countries listed in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, having returned to top 100 of this list for the first time since 2009, but dropped down one spot to 97th place in 2021, being characterized as being in a "difficult situation".

The mass media in Kosovo consists of different kinds of communicative media such as radio, television, newspapers, and internet web sites. Most of the media survive from advertising and subscriptions.

Most Azerbaijanis receive their information from mainstream television, which is unswervingly pro-government and under strict government control. According to a 2012 report of the NGO "Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety (IRFS)" Azerbaijani citizens are unable to access objective and reliable news on human rights issues relevant to Azerbaijan and the population is under-informed about matters of public interest.

Censorship in Armenia is generally non-existent, except in some limited incidents.

N1 is a 24-hour cable news channel launched on 30 October 2014. The channel has headquarters in Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade and Sarajevo and covers events happening in Central and Southeastern Europe. Available on cable TV throughout former Yugoslavia, N1 is CNN International's local broadcast partner and affiliate via an agreement with the London-based Warner Bros. Discovery EMEA. As it is focused on the audiences of the three countries in which it is headquartered, it has three separate editorial policies, separate reporters, TV studios as well as internet and mobile platforms. In cases where news overlaps, it is presented jointly.

Censorship in Serbia is prohibited by the Constitution. Freedom of expression and of information are protected by international and national law, even if the guarantees enshrined in the laws are not coherently implemented. Instances of censorship and self-censorship are still reported in the country.

Censorship in Ecuador refers to all actions which can be considered as suppression in speech in Ecuador. In the Freedom of the Press Report 2016 by Freedom House, the press in Ecuador is classified as "not free". The 2016 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders placed Ecuador in the "noticeable problems" category for press freedom, ranking the country 109 out of 180.

In late 2018, a series of largely peaceful protests over the rise of political violence and against the authoritarian rule of Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and his governing Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) began to take place in the Serbian capital of Belgrade, soon spreading to cities across the country, as well as in cities with the Serbian diaspora. The demonstrations have lasted more than a year and they become the most prolonged mass anti-government demonstrations in Serbia since the time of the Bulldozer Revolution and some of the longest-running in Europe.

Freedom of the press in Pakistan is legally protected by the law of Pakistan as stated in its constitutional amendments, while the sovereignty, national integrity, and moral principles are generally protected by the specified media law, Freedom of Information Ordinance 2002, and Code of Conduct Rules 2010. In Pakistan, the code of conduct and ordinance act comprises a set of rules for publishing, distributing, and circulating news stories and operating media organizations working independently or running in the country.