Related Research Articles

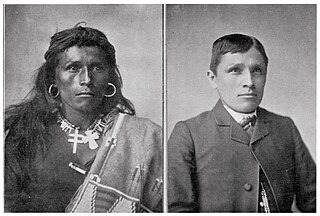

The Dawes Act of 1887 regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the President of the United States to subdivide Native American tribal communal landholdings into allotments for Native American heads of families and individuals. This would convert traditional systems of land tenure into a government-imposed system of private property by forcing Native Americans to "assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property" that did not previously exist in their cultures. The act allowed tribes the option to sell the lands that remained after allotment to the federal government. Before private property could be dispensed, the government had to determine which Indians were eligible for allotments, which propelled an official search for a federal definition of "Indian-ness".

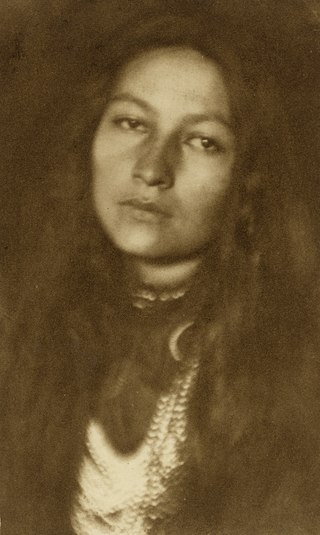

Zitkala-Ša, also Zitkála-Šá, was a Yankton Dakota writer, editor, translator, musician, educator, and political activist. She was also known by her Anglicized and married name, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin. She wrote several works chronicling her struggles with cultural identity, and the pull between the majority culture in which she was educated, and the Dakota culture into which she was born and raised. Her later books were among the first works to bring traditional Native American stories to a widespread white English-speaking readership.

Amelia Stone Quinton was an American social activist and advocate for Native American rights. In collaboration with Mary Bonney, she helped found the Women's National Indian Association in 1883.

The Women's National Indian Association (WNIA) was founded in 1879 by a group of American women, including educators and activists Mary Bonney and Amelia Stone Quinton. Bonney and Quinton united in the 1880s against the encroachment of white settlers on land set aside for Native Americans in Indian Territory. They drew up a petition that addressed the binding obligation of treaties between the United States and Native American nations. The petition was circulated for signature in sixteen states and was presented to President Rutherford B. Hayes at the White House and in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1880.

Alice Cunningham Fletcher was an American ethnologist, anthropologist, and social scientist who studied and documented Native American culture.

The Indian Rights Association (IRA) was a social activist group dedicated to the well-being and acculturation of Native Americans in the United States. Founded by non-Indians in Philadelphia in 1882, the group was highly influential in American Indian policy through the 1930s and remained an organization until 1994. The organization's initial objective was to "bring about the complete civilization of the Indians and their admission to citizenship."

The Society of American Indians (1911–1923) was the first national American Indian rights organization run by and for American Indians. The Society pioneered twentieth century Pan-Indianism, the movement promoting unity among American Indians regardless of tribal affiliation. The Society was a forum for a new generation of American Indian leaders known as Red Progressives, prominent professionals from the fields of medicine, nursing, law, government, education, anthropology and ministry. They shared the enthusiasm and faith of Progressive Era white reformers in the inevitability of progress through education and governmental action.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, was an Act of the United States Congress that imposed U.S. citizenship on the indigenous peoples of the United States. While the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution defines a citizen as any persons born in the United States and subject to its laws and jurisdiction, the amendment had previously been interpreted by the courts not to apply to Native peoples.

The Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions was a Roman Catholic institution created in 1874 by J. Roosevelt Bayley, Archbishop of Baltimore, for the protection and promotion of Catholic mission interests among Native Americans in the United States.

A series of efforts were made by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920. George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans. They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process". With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the acculturation process for minorities.

James McLaughlin was a Canadian-American United States Indian agent and inspector, best known for having ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull in December 1890, which resulted in the chief's death and contributed to the Wounded Knee Massacre. Before this event, he was known for his positive relations with several tribes. His memoir, published in 1910, was entitled, My Friend the Indian.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee is a 2007 American Western historical drama television film adapted from the 1970 book of the same name by Dee Brown. The film was written by Daniel Giat, directed by Yves Simoneau and produced by HBO Films.

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke. Historically, they were often referred to by European Americans as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.

Native American civil rights are the civil rights of Native Americans in the United States. Native Americans are citizens of their respective Native nations as well as of the United States, and those nations are characterized under United States law as "domestic dependent nations", a special relationship that creates a tension between rights retained via tribal sovereignty and rights that individual Natives have as U.S. citizens. This status creates tension today but was far more extreme before Native people were uniformly granted U.S. citizenship in 1924. Assorted laws and policies of the United States government, some tracing to the pre-Revolutionary colonial period, denied basic human rights—particularly in the areas of cultural expression and travel—to indigenous people.

The Meriam Report (1928) was commissioned by the Institute for Government Research and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The IGR appointed Lewis Meriam to be the technical director of the survey team to compile information and report on the conditions of American Indians across the country. Meriam submitted the 847-page report to the Secretary of the Interior, Hubert Work, on February 21, 1928.

The Board of Indian Commissioners was a committee that advised the federal government of the United States on Native American policy and inspected supplies delivered to Indian agencies to ensure the fulfillment of government treaty obligations.

The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by President Benjamin Harrison to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

Thomas Louis Sloan was a Native American lawyer and activist. Sloan worked alongside his partner, Hiram Chase, for much of his career. Sloan has a history of activism dating back to his teenage years. In 1911, he helped found the Society of American Indians. In addition, he established the first Indian-owned law office in Washington D.C. in 1912. Sloan was an activist for the citizenship of all Native Americans.

Dolly Akers was an Assiniboine woman who was the first Native American woman elected to the Montana Legislature with 100% of the Indian vote and the first woman elected to the Tribal Executive Board of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation.

The Friends of the Indian was a group that pushed for Indian assimilation during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After dealing with "the Indian problem" through treaties, removal, and reservations, the Federal Government of The United States moved toward a method that is now referred to as assimilation. The Friends of the Indian group, which was largely connected to and intertwined with the Office of Indian Affairs within the Federal Government presented themselves as speaking on behalf of Native Americans who they viewed as unable to speak for themselves. They claimed that the best course of action for Native Americans was to assimilate them into the larger American culture, rather than allowing them to maintain their existing native cultures. The Friends used many tactics to push for said assimilation. Some went and lived with tribes, or contributed to the new discipline of anthropology to establish themselves as experts and push for cultural change. Some wrote books and essays about the poor treatment of Indians they had seen in the past and how this treatment might be improved. Others lobbied for legislative change through the Federal Government. The Friends of the Indian played a large role in the assimilation of American Indians by pushing for the passing of the Dawes Act, the Indian Citizenship Act, the creation and use of Indian boarding schools, and the continuation of an expectation that Indians could not speak for themselves.

References

- ↑ "STRICKEN WITH HEART DISEASE; Indian Commissioner Painter Dies Suddenly in Washington". The New York Times . January 14, 1895. p. 2. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ↑ Mathes, Valerie Sherer (2020). Charles C. Painter: the life of an Indian reform advocate. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806166322.