Gainesville is the county seat of Alachua County, Florida, and the largest city in North Central Florida, with a population of 141,085 in 2020. It is the principal city of the Gainesville metropolitan area, which had a population of 339,247 in 2020.

The Independent Florida Alligator is the daily student newspaper of the University of Florida. The Alligator is one of the largest student-run newspapers in the United States, with a daily circulation of 35,000 and readership of more than 52,000. It is an affiliate of UWIRE, which distributes and promotes its content to their network.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people (LGBT) in the Philippines face legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT people, with legislations struggling to be passed on a national level, while some only existing on a local government level.

Cynthia Moore Chestnut is an American Democratic politician who served on the Gainesville, Florida City Commission from 1987 to 1989 and as a member of the Florida House of Representatives from 1990 to 2000, representing the 23rd District. After unsuccessfully running for the Florida Senate in 2000, Chestnut was elected to the Alachua County Commission in 2002, where she served until she lost re-election in 2010.

Save Our Children, Inc. was an American political coalition formed in 1977 in Miami, Florida, to overturn a recently legislated county ordinance that banned discrimination in areas of housing, employment, and public accommodation based on sexual orientation. The coalition was publicly headed by celebrity singer Anita Bryant, who claimed the ordinance discriminated against her right to teach her children biblical morality. It was a well-organized campaign that initiated a bitter political fight between gay activists and Christian fundamentalists. When the repeal of the ordinance went to a vote, it attracted the largest response of any special election in Dade County's history, passing by 70%. In response to this vote, a group of gay and lesbian community members formed Pride South Florida, now known as Pride Fort Lauderdale, an organization whose mission was to fight for the rights of the gay and lesbian community in South Florida.

Simply Equal is a grassroots coalition that formed to petition the city of Lawrence, Kansas, to add the words "sexual orientation" to its Human Relations Ordinance. In May 1995, Lawrence passed the "Simply Equal Amendment," thus becoming the first city in Kansas to prohibit discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Michigan may face some legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Michigan, as is same-sex marriage. Discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity is illegal since July 2022, was re-affirmed by the Michigan Supreme Court - under and by a 1976 statewide law, that explicitly bans discrimination "on the basis of sex". The Michigan Civil Rights Commission have also ensured that members of the LGBT community are not discriminated against and are protected in the eyes of the law since 2018.

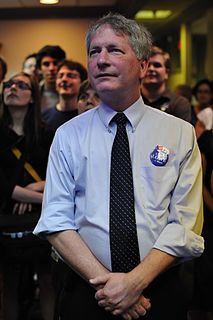

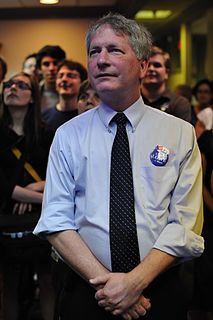

Stuart Craig Lowe is an American politician and former Mayor of Gainesville, Florida. After winning a runoff election on April 13, 2010, by a margin of 42 votes Lowe became mayor-elect of Gainesville. He was sworn in on May 20, 2010, becoming the first openly gay mayor of the city. He lost his bid for re-election on April 16, 2013 to former City Commissioner Ed Braddy after being arrested for a DUI during the campaign.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Florida may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity became legal in the state after the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Lawrence v. Texas on June 26, 2003, and same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since January 6, 2015. Discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations is outlawed following the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County. In addition, several cities and counties, comprising about 55% of Florida's population, have enacted anti-discrimination ordinances. These include Jacksonville, Miami, Tampa, Orlando, St. Petersburg, Tallahassee and West Palm Beach, among others. Conversion therapy is also banned in a number of cities in the state, mainly in Palm Beach County and the Miami metropolitan area.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Wisconsin have many of the same rights and responsibilities as heterosexuals; however, the transgender community may face some legal issues not experienced by cisgender residents, due in part to discrimination based on gender identity not being included in Wisconsin's anti-discrimination laws, nor is it covered in the state's hate crime law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Wisconsin since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Wolf v. Walker. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned statewide in Wisconsin, and sexual orientation is a protected class in the state's hate crime laws. It approved such protections in 1982, making it the first state in the United States to do so.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Indiana enjoy most of the same rights as other people. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Indiana since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Baskin v. Bogan.

Warren ‘Keith’ Perry is a Republican member of the Florida Senate, representing the 8th district, encompassing Alachua, Putnam, and part of Marion County in North Central Florida, since 2016. He also served in the Florida House of Representatives, representing the 22nd district from 2010 to 2012 and the 21st district from 2012 to 2016.

The Mayor of Gainesville is, for ceremonially purposes, receipt of service of legal processes and the purposes of military law, official head of the city of Gainesville, Florida and otherwise a member of, and chair of, the city commission, required to preside at all meetings thereof. The mayor is also allowed to vote on all matters that come before the city commission, but has no veto powers.

Eugene Local Measure 51 was a 1978 petition calling for a referendum in Eugene, Oregon, to repeal Ordinance no. 18080, which prohibited sexual orientation discrimination in the city. VOICE created and campaigned for the petition, and gathered enough signatures to force a referendum vote. Measure 51 passed with 22,898 votes for and 13,427 against. This bill's passage garnered national attention, with Miami anti-gay activist Anita Bryant's telegram congratulating VOICE on the victory. It is the earliest example of 35 ballot measures to limit gay rights in Oregon.

The Alachua County Labor Coalition (ACLC) is a nonprofit organization in Alachua County, Florida, that advocates for working people. The organization was formerly known as the Alachua County Labor Party and traces its roots to the national Labor Party's call in 1996 for a new political party as a reaction to the conservative, neoliberal New Democrat movement.

Amendment 2 was a ballot measure approved by Colorado voters on November 3, 1992, simultaneously with the United States presidential election. The amendment prevented municipalities from enacting anti-discrimination laws protecting gay, lesbian, or bisexual people.