Related Research Articles

A tobacco pipe, often called simply a pipe, is a device specifically made to smoke tobacco. It comprises a chamber for the tobacco from which a thin hollow stem (shank) emerges, ending in a mouthpiece. Pipes can range from very simple machine-made briar models to highly prized hand-made artisanal implements made by renowned pipemakers, which are often very expensive collector's items. Pipe smoking is the oldest known traditional form of tobacco smoking.

Catlinite, also called pipestone, is a type of argillite, usually brownish-red in color, which occurs in a matrix of Sioux Quartzite. Because it is fine-grained and easily worked, it is prized by Native Americans, primarily those of the Plains nations, for use in making ceremonial pipes, known as chanunpas or čhaŋnúŋpas in the Lakota language. Pipestone quarries are located and preserved in Pipestone National Monument outside Pipestone, Minnesota, in Pipestone County, Minnesota, and at the Pipestone River in Ontario, Canada.

The Chesapeake Colonies were the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, later the Commonwealth of Virginia, and Province of Maryland, later Maryland, both colonies located in British America and centered on the Chesapeake Bay. Settlements of the Chesapeake region grew slowly due to diseases such as malaria. Most of these settlers were male immigrants from England who died soon after their arrival. Due to the majority of men, eligible women did not remain single for long. The native-born population eventually became immune to the Chesapeake diseases and these colonies were able to continue through all the hardships.

Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800, is a book written by historian Allan Kulikoff. Published in 1986, it is the first major study that synthesized the historiography of the colonial Chesapeake region of the United States. Tobacco and Slaves is a neo-Marxist study that explains the creation of a racial caste system in the tobacco-growing regions of Maryland and Virginia and the origins of southern slave society. Kulikoff uses statistics compiled from colonial court and church records, tobacco sales, and land surveys to conclude that economic, political, and social developments in the 18th-century Chesapeake established the foundations of economics, politics, and society in the 19th-century South.

A smoking pipe is used to taste the smoke of a burning substance; most common is a tobacco pipe. Pipes are commonly made from briar, heather, corn, meerschaum, clay, cherry, glass, porcelain, ebonite and acrylic.

Henry Town, Henry Towne, or Henries Towne was an early English colonial settlement near Cape Henry, the southern point and gateway to the Chesapeake Bay in the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, now in modern Virginia Beach, Virginia, on the East Coast of the United States. Archaeologist Floyd Painter of the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences originally excavated the site in 1955, but it was only conclusively determined to be Henry Town in 2007 by United States Army scientists reviewing the site's artifacts, and no primary source documents exist. It was located east of Norfolk, Virginia and north of Chesapeake and south of the Hampton Roads harbor at approximately 36°54′30″N76°7′20″W. The historical and archeological site is immediately north of U.S. Route 60 on what is now Lake Joyce, formerly an inlet connecting with Pleasure House Creek, a western branch of the Lynnhaven River, itself an estuary of the Chesapeake Bay and Hampton Roads.

The history of commercial tobacco production in the United States dates back to the 17th century when the first commercial crop was planted. The industry originated in the production of tobacco for British pipes and snuff. See Tobacco in the American colonies. In late 18th century there was an increase in demand for tobacco in the United States, where the demand for tobacco in the form of cigars and chewing tobacco increased. In the late 19th century production shifted to the manufactured cigarette.

During the British colonization of North America, the Thirteen Colonies provided England with an outlet for surplus population as well as a new market. The colonies exported naval stores, fur, lumber and tobacco to Britain, and food for the British sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The culture of the Southern and Chesapeake Colonies was different from that of the Northern and Middle Colonies and from that of their common origin in the Kingdom of Great Britain.

The history of smoking dates back to as early as 5000 BC in the Americas in shamanistic rituals. With the arrival of the Europeans in the 16th century, the consumption, cultivation, and trading of tobacco quickly spread. The modernization of farming equipment and manufacturing increased the availability of cigarettes following the reconstruction era in the United States. Mass production quickly expanded the scope of consumption, which grew until the scientific controversies of the 1960s, and condemnation in the 1980s.

Tobacco cultivation and exports formed an essential component of the American colonial economy. It was distinct from rice, wheat, cotton and other cash crops in terms of agricultural demands, trade, slave labor, and plantation culture. Many influential American revolutionaries, including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, owned tobacco plantations, and were hurt by debt to British tobacco merchants shortly before the American Revolution. For the later period see History of commercial tobacco in the United States.

The Mississippian stone statuary are artifacts of polished stone in the shape of human figurines made by members of the Mississippian culture and found in archaeological sites in the American Midwest and Southeast. Two distinct styles exist; the first is a style of carved flint clay found over a wide geographical area but believed to be from the American Bottom area and manufactured at the Cahokia site specifically; the second is a variety of carved and polished locally available stone primarily found in the Tennessee-Cumberland region and northern Georgia. Early European explorers reported seeing stone and wooden statues in native temples, but the first documented modern discovery was made in 1790 in Kentucky, and given as a gift to Thomas Jefferson.

A ceremonial pipe is a particular type of smoking pipe, used by a number of cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in their sacred ceremonies. Traditionally they are used to offer prayers in a religious ceremony, to make a ceremonial commitment, or to seal a covenant or treaty. The pipe ceremony may be a component of a larger ceremony, or held as a sacred ceremony in and of itself. Indigenous peoples of the Americas who use ceremonial pipes have names for them in each culture's Indigenous language. Not all cultures have pipe traditions, and there is no single word for all ceremonial pipes across the hundreds of diverse Native American languages.

Colonoware, which is alternately called Colono-Indian Ware, is a type of earthenware created by African Americans along the Atlantic Coast ranging north and south from Delaware to Florida and as far west as Tennessee and Kentucky beginning in the Colonial Era. It was first identified by the British archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume and shortly thereafter published in a book he wrote.

Potomac Creek, or 44ST2, is a late Native American village located on the Potomac River in Stafford County, Virginia. It is from the Woodland Period and dates from 1300 to 1550. There is another Potomac Creek site, 44ST1 or Indian Point, which was occupied by the Patawomeck during the historic period and is where Captain John Smith visited. This site no longer exists, as it eroded away into the river. Site 44ST2 has five ossuaries, one individual burial, and one multiple burial. Other names for the site are Potowemeke and Patawomeke. The defining features include distinctive ceramics, ossuary burials, and palisade villages.

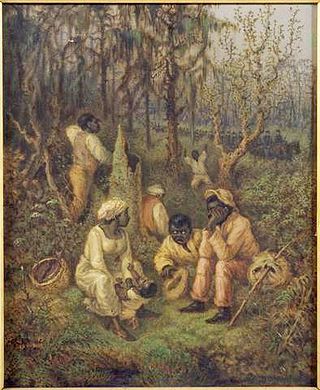

The Great Dismal Swamp maroons were people who inhabited the swamplands of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina after escaping enslavement. Although conditions were harsh, research suggests that thousands lived there between about 1700 and the 1860s. Harriet Beecher Stowe told the maroon people's story in her 1856 novel Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. The most significant research on the settlements began in 2002 with a project by Dan Sayers of American University.

The Amsterdam Pipe Museum is a museum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, dedicated to smoking pipes, tobacco, and related paraphernalia. It holds the national reference collection in these areas.

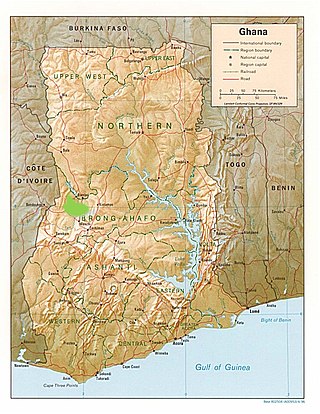

Banda District in Ghana plays an important role in the understanding of trade networks and the way they shaped the lives of people living in western Africa. Banda District is located in West Central Ghana, just south of the Black Volta River in a savanna woodland environment. This region has many connections to trans-Saharan trade, as well as Atlantic trade and British colonial and economic interests. The effects of these interactions can be seen archaeologically through the presence of exotic goods and export of local materials, production of pottery and metals, as well as changes in lifestyle and subsistence patterns. Pioneering archaeological research in this area was conducted by Ann Stahl.

White pipe clay is a white-firing clay of the sort that is used to make tobacco smoking pipes, which tended to be treated as disposable objects. This suited pipeclay, which is not very strong.

Eduard Bird was an English tobacco pipe maker who spent most of his life in Amsterdam. His life has been reconstructed by analysis of public registers, probate records, and notary and police records, by historians such as Don Duco and Margriet De Roever from the 1970s onwards. Pipes with the "EB" stamp have been found around the world.

Clay pipe dating is the act of dating clay tobacco pipes found at archaeological sites to specific time periods.

References

- ↑ Henry 1979.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 47.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999. p. 95.

- ↑ Emerson 1999.

- ↑ Ferguson 1992.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999. p. 97.

- ↑ Ferguson 1992. p. 50.

- ↑ Epperson 1999. p. 160.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999. p. 101.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 51.

- ↑ Curtin 1969. p. 122.

- ↑ Curtin 1969. p. 125.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 52.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 50.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 53.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 53.

- ↑ Stewart 1954. p. 04.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 54.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 54.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999. pp. 97-98.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. p. 56.

- ↑ Harrington 1951. p. n.p.

- ↑ Emerson 1999. pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Mouer et al 1999. pp. 91-92.

Academic books

- Curtin, Philip D. (1969). The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census . Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Ferguson, Leland (1992). Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650-1800. Washington D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Academic articles

- Emerson, Matthew C. (1999). "African Inspirations in a New World Art and Artifact: Decorated Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake". In Singleton, Theresa A. (ed.). "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia. pp. 47–81.

- Epperson, Terrence W. (1999). "The Chesapeake Plantation's Social and Spatial Order". In Singleton, Theresa A. (ed.). "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia. pp. 159–172.

- Henry, Susan (1979). "Terra-cotta Tobacco Pipes in 17th Century Maryland and Virginia: A Preliminary Study". Historical Archaeology. 13: 14–37. doi:10.1007/BF03373447. S2CID 160876860.

- Mouer, L. Daniel; Hodges, Mary Ellen N.; Potter, Stephen R.; Henry Renaud, Susan L.; Noel Hume, Ivor; Pogue, Dennis J.; McCartney, Martha W.; Davidson, Thomas E. (1999). "Colonoware Pottery, Chesapeake Pipes, and Uncritical Assumptions". In Singleton, Theresa A. (ed.). "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia.

- Stewart, T. Dale (1954). "A Method for Analyzing and Reproducing Pipe Decorations". Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Virginia. 09 (1).