Zugzwang is a situation found in chess and other turn-based games wherein one player is put at a disadvantage because of their obligation to make a move; a player is said to be "in zugzwang" when any legal move will worsen their position.

The Game of the Century is a chess game that was won by the 13-year-old future world champion Bobby Fischer against Donald Byrne in the Rosenwald Memorial Tournament at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City on October 17, 1956. In Chess Review, Hans Kmoch dubbed it "The Game of the Century" and wrote: "The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies."

The Plachutta is a device found in chess problems wherein a piece is sacrificially positioned in blockade to deny coverage of multiple distant squares required by the opposition. For example, two of an opponent's bishops, queen, or rooks are defending locations through an intersection square, and an enemy unit moved into that square blocks disrupts coverage in such a way that, even if captured, the previous defensive situation cannot be restored.

In the game of chess, an endgame study, or just study, is a composed position—that is, one that has been made up rather than played in an actual game—presented as a sort of puzzle, in which the aim of the solver is to find the essentially unique way for one side to win or draw, as stipulated, against any moves the other side plays. If the study does not end in the end of the game, then the game's eventual outcome should be obvious, and White can have a selection of many different moves. There is no limit to the number of moves which are allowed to achieve the win; this distinguishes studies from the genre of direct mate problems. Such problems also differ qualitatively from the very common genre of tactical puzzles based around the middlegame, often based on an actual game, where a decisive tactic must be found.

In chess, a smothered mate is a checkmate delivered by a knight in which the mated king is unable to move because it is completely surrounded by its own pieces, which a knight can jump over.

Caïssa is a fictional (anachronistic) Thracian dryad portrayed as the goddess of chess. She was first mentioned during the Renaissance by Italian poet Hieronymus Vida.

The two knights endgame is a chess endgame with a king and two knights versus a king. In contrast to a king and two bishops, or a bishop and a knight, a king and two knights cannot force checkmate against a lone king. Although there are checkmate positions, a king and two knights cannot force them against proper, relatively easy defense.

Anderssen's Opening is a chess opening defined by the opening move:

In chess, promotion is the replacement of a pawn with a new piece when the pawn is moved to its last rank. The player replaces the pawn immediately with a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. The new piece does not have to be a previously captured piece. Promotion is mandatory when moving to the last rank; the pawn cannot remain as a pawn.

The Tarrasch rule is a general principle that applies in the majority of chess middlegames and endgames. Siegbert Tarrasch (1862–1934) stated the "rule" that rooks should be placed behind passed pawns – either the player's or the opponent's. The idea behind the guideline is that (1) if a player's rook is behind their own passed pawn, the rook protects it as it advances, and (2) if it is behind an opponent's passed pawn, the pawn cannot advance unless it is protected along its way.

The rook and pawn versus rook endgame is a fundamentally important, widely studied chess endgame. Precise play is usually required in these positions. With optimal play, some complicated wins require sixty moves to either checkmate, capture the defending rook, or successfully promote the pawn. In some cases, thirty-five moves are required to advance the pawn once.

In chess, a blunder is a critically bad mistake that severely worsens the player's position by allowing a loss of material, checkmate, or anything similar. It is usually caused by some tactical oversight, whether due to time trouble, overconfidence, or carelessness. Although blunders are most common in beginner games, all human players make them, even at the world championship level. Creating opportunities for the opponent to blunder is an important skill in over-the-board chess.

In chess, a desperado is a piece that is either en prise or trapped, but captures an enemy piece before it is itself captured in order to compensate the loss a little, or is used as a sacrifice that will result in stalemate if it is captured. The former case can arise in a situation where both sides have hanging pieces, in which case these pieces are used to win material prior to being captured. A desperado in the latter case is usually a rook or a queen; such a piece is sometimes also called crazy or mad.

A joke chess problem is a puzzle in chess that uses humor as an element. Although most chess problems, like other creative forms, are appreciated for serious artistic themes, joke chess problems are enjoyed for some twist. In some cases the composer plays a trick to prevent a solver from succeeding with typical analysis. In other cases, the humor derives from an unusual final position. Unlike in ordinary chess puzzles, joke problems can involve a solution which violates the inner logic or rules of the game.

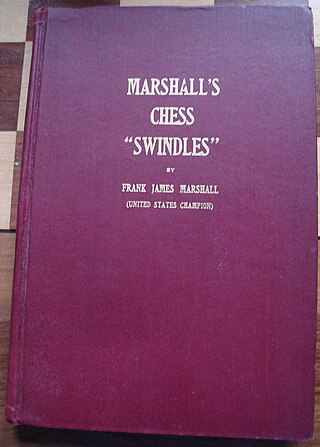

In chess, a swindle is a ruse by which a player in a losing position tricks their opponent and thereby achieves a win or draw instead of the expected loss. It may also refer more generally to obtaining a win or draw from a clearly losing position. I. A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld distinguish among "traps", "pitfalls", and "swindles". In their terminology, a "trap" refers to a situation where players go wrong through their own efforts. In a "pitfall", the beneficiary of the pitfall plays an active role, creating a situation where a plausible move by the opponent will turn out badly. A "swindle" is a pitfall adopted by a player who has a clearly lost game. Horowitz and Reinfeld observe that swindles, "though ignored in virtually all chess books", "play an enormously important role in over-the-board chess, and decide the fate of countless games".

Chess became a source of inspiration in the arts in literature soon after the spread of the game to the Arab World and Europe in the Middle Ages. The earliest works of art centered on the game are miniatures in medieval manuscripts, as well as poems, which were often created with the purpose of describing the rules. After chess gained popularity in the 15th and 16th centuries, many works of art related to the game were created. One of the best-known, Marco Girolamo Vida's poem Scacchia ludus, written in 1527, made such an impression on the readers that it singlehandedly inspired other authors to create poems about chess.

The opposite-colored bishops endgame is a chess endgame in which each side has a single bishop and those bishops operate on opposite-colored squares. Without other pieces besides pawns and the kings, these endings are widely known for their tendency to result in a draw. These are the most difficult endings in which to convert a small material advantage to a win. With additional pieces, the stronger side has more chances to win, but still not as many as when bishops are on the same color.

The game of chess is commonly divided into three phases: the opening, middlegame, and endgame. There is a large body of theory regarding how the game should be played in each of these phases, especially the opening and endgame. Those who write about chess theory, who are often also eminent players, are referred to as "chess theorists" or "chess theoreticians".

The queen and pawn versus queen endgame is a chess endgame in which both sides have a queen and one side has a pawn, which one tries to promote. It is very complicated and difficult to play. Cross-checks are often used as a device to win the game by forcing the exchange of queens. It is almost always a draw if the defending king is in front of the pawn.

The queen versus rook endgame is a chess endgame where one player has just a king and queen, and the other player has just a king and rook. As no pawns are on the board, it is a pawnless chess endgame. The side with the queen wins with best play, except for a few rare positions where the queen is immediately lost, or because a draw by stalemate or perpetual check can be forced. However, the win is difficult to achieve in practice, especially against precise defense.