Yucatán, officially the Estado Libre y Soberano de Yucatán, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate municipalities, and its capital city is Mérida.

Observational learning is learning that occurs through observing the behavior of others. It is a form of social learning which takes various forms, based on various processes. In humans, this form of learning seems to not need reinforcement to occur, but instead, requires a social model such as a parent, sibling, friend, or teacher with surroundings. Particularly in childhood, a model is someone of authority or higher status in an environment. In animals, observational learning is often based on classical conditioning, in which an instinctive behavior is elicited by observing the behavior of another, but other processes may be involved as well.

Mérida is the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán, and the largest city in southeastern Mexico. The city is also the seat of the eponymous municipality. It is located in the northwest corner of the Yucatán Peninsula, about 35 km inland from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. In 2020, it had a population of 921,770 while its metropolitan area, which also includes the cities of Kanasín and Umán, had a population of 1,316,090.

The Mayan languages form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica, both in the south of Mexico and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Maya people, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight within its territory.

The Maya are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical region. Today they inhabit southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and westernmost El Salvador and Honduras.

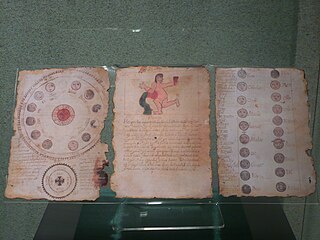

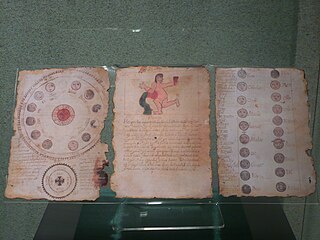

The Books of Chilam Balam are handwritten, chiefly 17th and 18th-centuries Maya miscellanies, named after the small Yucatec towns where they were originally kept, and preserving important traditional knowledge in which indigenous Maya and early Spanish traditions have coalesced. They compile knowledge on history, prophecy, religion, ritual, literature, the calendar, astronomy, and medicine. Written in the Yucatec Maya language and using the Latin alphabet, the manuscripts are attributed to a legendary author called Chilam Balam, a chilam being a priest who gives prophecies and balam a common surname meaning ʼjaguarʼ. Some of the texts actually contain prophecies about the coming of the Spaniards to Yucatán while mentioning a chilam Balam as their first author.

Collaborative learning is a situation in which two or more people learn or attempt to learn something together. Unlike individual learning, people engaged in collaborative learning capitalize on one another's resources and skills. More specifically, collaborative learning is based on the model that knowledge can be created within a population where members actively interact by sharing experiences and take on asymmetric roles. Put differently, collaborative learning refers to methodologies and environments in which learners engage in a common task where each individual depends on and is accountable to each other. These include both face-to-face conversations and computer discussions. Methods for examining collaborative learning processes include conversation analysis and statistical discourse analysis.

Yucatec Maya is a Mayan language spoken in the Yucatán Peninsula, including part of northern Belize. There is also a significant diasporic community of Yucatec Maya speakers in San Francisco, though most Maya Americans are speakers of other Mayan languages from Guatemala and Chiapas.

Mayan Sign Language is a sign language used in Mexico and Guatemala by Mayan communities with unusually high numbers of deaf inhabitants. In some instances, both hearing and deaf members of a village may use the sign language. It is unrelated to the national sign languages of Mexico and Guatemala, as well as to the local spoken Mayan languages and Spanish.

Youth participation is the active engagement of young people throughout their own communities. It is often used as a shorthand for youth participation in any many forms, including decision-making, sports, schools and any activity where young people are not historically engaged.

Barbara Rogoff is an American academic who is UCSC Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her research is in different learning between cultures and bridges psychology and anthropology.

Team learning is the collaborative effort to achieve a common goal within the group. The aim of team learning is to attain the objective through dialogue and discussion, conflicts and defensive routines, and practice within the group. In the same way, indigenous communities of the Americas exhibit a process of collaborative learning.

Informal learning is characterized "by a low degree of planning and organizing in terms of the learning context, learning support, learning time, and learning objectives". It differs from formal learning, non-formal learning, and self-regulated learning, because it has no set objective in terms of learning outcomes, but an intent to act from the learner's standpoint. Typical mechanisms of informal learning include trial and error or learning-by-doing, modeling, feedback, and reflection. For learners this includes heuristic language building, socialization, enculturation, and play. Informal learning is a pervasive ongoing phenomenon of learning via participation or learning via knowledge creation, in contrast with the traditional view of teacher-centered learning via knowledge acquisition. Estimates suggest that about 70-90 percent of adult learning takes place informally and outside educational institutions.

The Huay Chivo is a legendary Maya beast. It is a half-man, half-beast creature, with burning red eyes, and is specific to the Yucatán Peninsula. It is reputed to be an evil sorcerer who can transform himself into a supernatural animal, usually a goat, dog or deer, in order to prey upon livestock. In recent times, it has become associated with the chupacabras. The Huay Chivo is specific to the southeastern Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche and Quintana Roo. Alleged Huay Chivo activity is sporadically reported in the regional press. Local Maya near the town of Valladolid, in Yucatán, believe the Huay Chivo is an evil sorcerer that is capable of transforming into a goat to do mischief and eat livestock.

Ancient Maya women had an important role in society: beyond propagating the culture through bearing and raising children, Maya women participated in economic, governmental, and farming activities. The lives of women in ancient Mesoamerica are not well documented: "Of the three elite founding area tombs discovered to date within the Copan Acropolis, two contain the remains of women, and yet there is not a single reference to a woman in either known contemporary texts or later retrospective accounts of Early Classic events and personages at Copan," writes a scholar.

Learning through play is a term used in education and psychology to describe how a child can learn to make sense of the world around them. Through play children can develop social and cognitive skills, mature emotionally, and gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

Indigenous education specifically focuses on teaching Indigenous knowledge, models, methods, and content within formal or non-formal educational systems. The growing recognition and use of Indigenous education methods can be a response to the erosion and loss of Indigenous knowledge through the processes of colonialism, globalization, and modernity.

Child work in indigenous American cultures covers child work, defined as the physical and mental contributions by children towards achieving a personal or communal goal, in Indigenous American societies. As a form of prosocial behavior, children's work is often a vital contribution towards community productivity and typically involves non-exploitative motivations for children's engagement in work activities. Activities can range from domestic household chores to participation in family and community endeavors. Inge Bolin notes that children's work can blur the boundaries between learning, play, and work in a form of productive interaction between children and adults. Such activities do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Styles of children’s learning across various indigenous communities in the Americas have been practiced for centuries prior to European colonization and persist today. Despite extensive anthropological research, efforts made towards studying children’s learning and development in Indigenous communities of the Americas as its own discipline within Developmental Psychology, has remained rudimentary. However, studies that have been conducted reveal several larger thematic commonalities, which create a paradigm of children’s learning that is fundamentally consistent across differing cultural communities.

Child integration is the inclusion of children in a variety of mature daily activities of families and communities. This contrasts with, for example, age segregation; separating children into age-defined activities and institutions. Integrating children in the range of mature family and community activities gives equal value and responsibility to children as contributors and collaborators, and can be a way to help them learn. Children's integration provides a learning environment because children are able to observe and pitch in as they feel they can.