During the early years of World War II, Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated from their homes on the West Coast because military leaders and public opinion combined to fan unproven fears of sabotage. As the war progressed, many of the young Nisei, Japanese immigrants' children who were born with American citizenship, volunteered or were drafted to serve in the United States military. Japanese Americans served in all the branches of the United States Armed Forces, including the United States Merchant Marine. An estimated 33,000 Japanese Americans served in the U.S. military during World War II, of which 20,000 joined the Army. Approximately 800 were killed in action.

A code talker was a person employed by the military during wartime to use a little-known language as a means of secret communication. The term is most often used for United States service members during the World Wars who used their knowledge of Native American languages as a basis to transmit coded messages. In particular, there were approximately 400 to 500 Native Americans in the United States Marine Corps whose primary job was to transmit secret tactical messages. Code talkers transmitted messages over military telephone or radio communications nets using formally or informally developed codes built upon their Indigenous languages. The code talkers improved the speed of encryption and decryption of communications in front line operations during World War II and are credited with a number of decisive victories. Their code was never broken.

The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POW) from the municipalities of Bagac and Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula to Camp O'Donnell via San Fernando.

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942, and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States as the WAC on 1 July 1943. Its first director was Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby. The WAC was disbanded in 1978, and all units were integrated with male units.

The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) was a civilian women pilots' organization, whose members were United States federal civil service employees. Members of WASP became trained pilots who tested aircraft, ferried aircraft, and trained other pilots. Their purpose was to free male pilots for combat roles during World War II. Despite various members of the armed forces being involved in the creation of the program, the WASP and its members had no military standing.

The 761st Tank Battalion was an independent tank battalion of the United States Army during World War II. Its ranks primarily consisted of African American soldiers, who by War Department policy were not permitted to serve in the same units as White troops; the United States Armed Forces did not officially desegregate until after World War II. The 761st were known as the Black Panthers after their distinctive unit insignia, which featured a black panther's head, and the unit's motto was "Come out fighting". During the war, the unit received a Presidential Unit Citation for its actions. In addition, a large number of individual members also received medals, including one Medal of Honor, eleven Silver Stars and approximately 300 Purple Hearts.

War brides are women who married military personnel from other countries in times of war or during military occupations, a practice that occurred in great frequency during World War I and World War II. Allied servicemen married many women in other countries where they were stationed at the end of the war, including the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, Greece, Luxembourg, the Philippines, China, and the Soviet Union. Similar marriages also occurred in Korea and Vietnam with the later wars in those countries involving U.S. troops and other anti-communist soldiers.

During World War II, the Allies committed legally proven war crimes and violations of the laws of war against either civilians or military personnel of the Axis powers. At the end of World War II, many trials of Axis war criminals took place, most famously the Nuremberg Trials and Tokyo Trials. In Europe, these tribunals were set up under the authority of the London Charter, which only considered allegations of war crimes committed by people who acted in the interests of the Axis powers. Some war crimes involving Allied personnel were investigated by the Allied powers and led in some instances to courts-martial. Some incidents alleged by historians to have been crimes under the law of war in operation at the time were, for a variety of reasons, not investigated by the Allied powers during the war, or were investigated but not prosecuted.

The military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. African Americans have participated in every war fought by or within the United States, including the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the Civil War, the Spanish–American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War.

Ethnic minorities in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II comprised about 13% of all military service members. All US citizens were equally subject to the draft, and all service members were subject to the same rate of pay. The 16 million men and women in the services included 1 million African Americans, along with 33,000+ Japanese-Americans, 20,000+ Chinese Americans, 24,674 American Indians, and some 16,000 Filipino-Americans. According to House concurrent resolution 253, 400,000 to 500,000 Hispanic Americans served. They were released from military service in 1945-46 on equal terms, and were eligible for the G.I. Bill and other veterans' benefits on a basis of equality. Many veterans, having learned organizational skills, and become more alert to the nationwide situation of their group, became active in civil rights activities after the war.

Mun Charn Wong was an American businessman. Wong served in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II along with his friend, Wah Kau Kong, the first Chinese American fighter pilot. He played football on the Air Force team and was a noted quarterback. After the war, Wong became a successful life insurance executive for the Transamerica Corporation. In 1989, the company recognized him as a "Legend of Transamerica", the highest honor awarded by the company.

The Military Intelligence Service was a World War II U.S. military unit consisting of two branches, the Japanese American unit and the German-Austrian unit based at Camp Ritchie, best known as the "Ritchie Boys". The unit described here was primarily composed of Nisei who were trained as linguists. Graduates of the MIS language school (MISLS) were attached to other military units to provide translation, interpretation, and interrogation services.

The Wehrmacht were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer (army), the Kriegsmarine (navy) and the Luftwaffe. The designation "Wehrmacht" replaced the previously used term Reichswehr and was the manifestation of the Nazi regime's efforts to rearm Germany to a greater extent than the Treaty of Versailles permitted.

Asian Americans, who are Americans of Asian descent, have fought and served on behalf of the United States since the American Revolutionary War. During the American Civil War Asian Americans fought for both the Union and the Confederacy. Afterwards Asian Americans served primarily in the U.S. Navy until the Philippine–American War.

As Allied troops entered and occupied German territory during the later stages of World War II, mass rapes of women took place both in connection with combat operations and during the subsequent occupation of Germany by soldiers from all advancing Allied armies, although a majority of scholars agree that the records show that a majority of the rapes were committed by Soviet occupation troops. The wartime rapes were followed by decades of silence.

The Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression or Chinese People's Anti-Japanese War Memorial Hall is a museum and memorial hall in Beijing. It is the most comprehensive museum in China about the Second Sino-Japanese War.

A series of policies were formerly issued by the U.S. military which entailed the separation of white and non-white American soldiers, prohibitions on the recruitment of people of color and restrictions of ethnic minorities to supporting roles. Since the American Revolutionary War, each branch of the United States Armed Forces implemented differing policies surrounding racial segregation. Racial discrimination in the U.S. military was officially opposed by Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981 in 1948. The goal was equality of treatment and opportunity. Jon Taylor says, "The wording of the Executive Order was vague because it neither mentioned segregation or integration." Racial segregation was ended in the mid-1950s.

Elizabeth L. Gardner was an American pilot during World War II who served as a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). She was one of the first American female military pilots and the subject of a well-known photograph, sitting in the pilot's seat of a Martin B-26 Marauder.

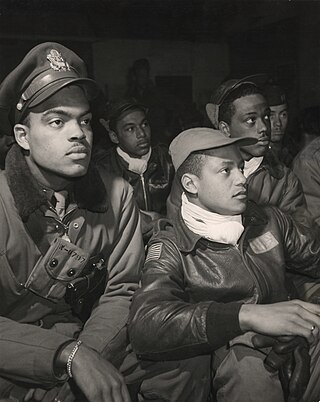

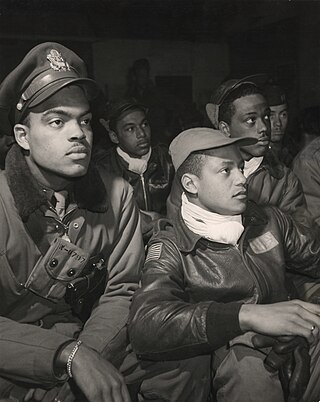

Sergeant First Class Thomas Franklin Vaughns is an American veteran who was a member of the famed group of World War II-era African-Americans known as the Tuskegee Airmen. He is a recipient of the National Defense Service Medal in 2019, for his service in the Korean War. He is also a member of the Arkansas Agriculture Hall of Fame.

E. Samantha Cheng is a Chinese-American journalist, author, and documentarian. She is best known for leading and advancing the "Chinese American WWII Veterans Recognition Project" which ultimately led to the passage of the "Chinese-American World War II Veteran Congressional Gold Medal Act" in 2018. She also cofounded the company Heritage Series, LLC, which creates educational material highlighting ethnic minorities in the United States.