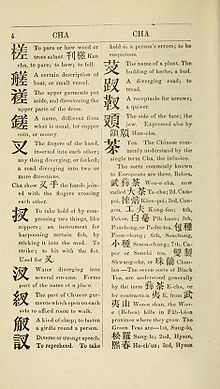

The Kangxi Dictionary is a Chinese dictionary published in 1716 during the High Qing, considered from the time of its publishing until the early 20th century to be the most authoritative reference for written Chinese characters. Wanting an improvement upon earlier dictionaries, as well as to show his concern for Confucian culture and to foster standardization of the Chinese writing system, its compilation was ordered by the Kangxi Emperor in 1710, from whom the compendium gets its name. The dictionary was the largest of its kind, containing 47,043 character entries. Around 40% of them were graphical variants, while others were dead, archaic, or found only once in the Classical Chinese corpus. In today's vernacular written Chinese, fewer than a quarter of the dictionary's characters are commonly used.

The Dai Kan-Wa Jiten is a Japanese dictionary of kanji compiled by Tetsuji Morohashi. Remarkable for its comprehensiveness and size, Morohashi's dictionary contains over 50,000 character entries and 530,000 compound words. Haruo Shirane (2003:15) said: "This is the definitive dictionary of the Chinese characters and one of the great dictionaries of the world."

Japanese dictionaries have a history that began over 1300 years ago when Japanese Buddhist priests, who wanted to understand Chinese sutras, adapted Chinese character dictionaries. Present-day Japanese lexicographers are exploring computerized editing and electronic dictionaries. According to Nakao Keisuke (中尾啓介):

It has often been said that dictionary publishing in Japan is active and prosperous, that Japanese people are well provided for with reference tools, and that lexicography here, in practice as well as in research, has produced a number of valuable reference books together with voluminous academic studies. (1998:35)

Han-Han Dae Sajeon is the generic term for Korean hanja-to-hangul dictionaries. There are several such dictionaries from different publishers. The most comprehensive one, published by Dankook University Publishing, contains 53,667 Chinese characters and 420,269 compound words. This dictionary was a project of the Dankook University Institute of Oriental Studies, which started in June 1977 and was completed 28 October 2008, and cost 31 billion KRW, or US$25 million. The dictionary comprises 16 volumes totalling over 20,000 pages.

The Xinhua Zidian, or Xinhua Dictionary, is a Chinese language dictionary published by the Commercial Press. It is the best-selling Chinese dictionary and the world's most popular reference work. In 2016, Guinness World Records officially confirmed that the dictionary, published by The Commercial Press, is the "Most popular dictionary" and the "Best-selling book ". It is considered a symbol of Chinese culture.

The Zhonghua Da Zidian is an unabridged Chinese dictionary of characters, originally published in 1915 by the Zhonghua Book Company in Shanghai. The chief editors were Xu Yuan'gao, Lufei Kui, and Ouyang Pucun (歐陽溥存/欧阳溥存). It was based upon the 1716 Kangxi Dictionary, and is internally organized using the 214 Kangxi radicals. The 1915 publication contains more than 48,000 entries for individual characters, including many invented in the two centuries since the Kangxi Dictionary, making it the largest character dictionary of its time.

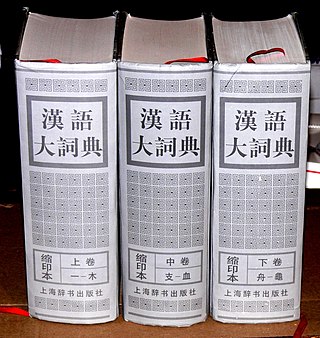

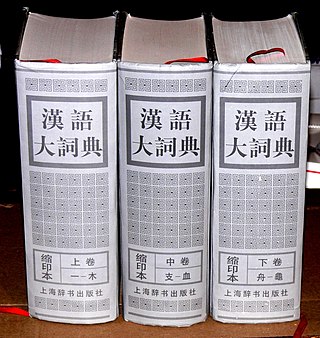

The Hanyu Da Cidian, also known as the Grand Chinese Dictionary, is the most inclusive available Chinese dictionary. Lexicographically comparable to the Oxford English Dictionary, it has diachronic coverage of the Chinese language, and traces usage over three millennia from Chinese classic texts to modern slang. The chief editor Luo Zhufeng (1911–1996), along with a team of over 300 scholars and lexicographers, started the enormous task of compilation in 1979. Publication of the thirteen volumes began with first volume in 1986 and ended with the appendix and index volume in 1994. In 1994, the dictionary also won the National Book Award of China.

The Hanyu Da Zidian, also known as the Grand Chinese Dictionary, is a reference dictionary on Chinese characters.

Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, also known as A Dictionary of Current Chinese or Contemporary Chinese Dictionary is an important one-volume dictionary of Standard Mandarin Chinese published by the Commercial Press, now into its 7th (2016) edition. It was originally edited by Lü Shuxiang and Ding Shengshu as a reference work on modern Standard Mandarin Chinese. Compilation started in 1958 and trial editions were issued in 1960 and 1965, with a number of copies printed in 1973 for internal circulation and comments, but due to the Cultural Revolution the final draft was not completed until the end of 1977, and the first formal edition was not published until December 1978. It was the first People's Republic of China dictionary to be arranged according to Hanyu Pinyin, the phonetic standard for Standard Mandarin Chinese, with explanatory notes in simplified Chinese. The subsequent second through seventh editions were respectively published in 1983, 1996, 2002, 2005, 2012 and 2016.

The Cihai is a large-scale dictionary and encyclopedia of Standard Mandarin Chinese. The Zhonghua Book Company published the first Cihai edition in 1938, and the Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House revised editions in 1979, 1989, 1999, and 2009. A standard bibliography of Chinese reference works calls the Cihai an "outstanding dictionary".

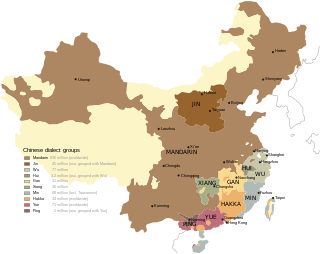

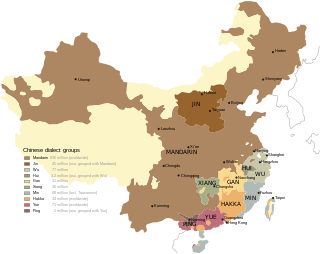

The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects is a compendium of dictionaries for 42 local varieties of Chinese following a common format. The individual dictionaries cover dialects spread across the dialect groups identified in the Language Atlas of China:

Yu Min was an influential Chinese linguist, a 1940 graduate of the Fu Jen Catholic University, Chinese Department, a former professor of Yenching University, and professor of Beijing Normal University. His primary research areas were Chinese historical linguistics, Sino-Tibetan comparison, the study of Sanskrit in Chinese transcription. His collected writings were published posthumously in 1999.

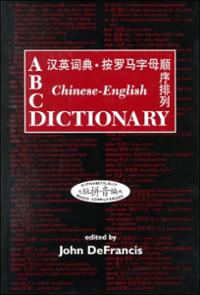

The ABC Chinese–English Dictionary or ABC Dictionary (1996), compiled under the chief editorship of John DeFrancis, is the first Chinese dictionary to collate entries in single-sort alphabetical order of pinyin romanization, and a landmark in the history of Chinese lexicography. It was also the first publication in the University of Hawaiʻi Press's "ABC" series of Chinese dictionaries. They republished the ABC Chinese–English Dictionary in a pocket edition (1999) and desktop reference edition (2000), as well as the expanded ABC Chinese–English Comprehensive Dictionary (2003), and dual ABC English–Chinese, Chinese–English Dictionary (2010). Furthermore, the ABC Dictionary databases have been developed into computer applications such as Wenlin Software for learning Chinese (1997).

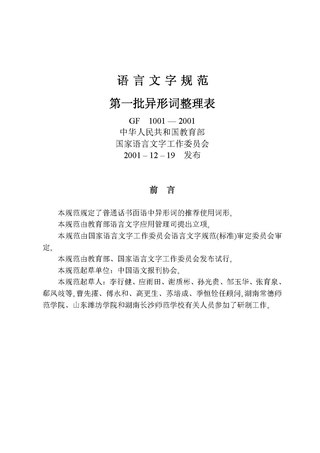

The First Series of Standardized Forms of Words with Non-standardized Variant Forms published on December 19, 2001 and officially implemented on March 31, 2002, is a Standard Chinese style guide published in China. It contains 338 Standard Chinese words that have variant written forms. In the First Series, one of the variant written forms for each word was selected as the recommended standard form.

Xiandai Hanyu Guifan Cidian is a dictionary of Standard Chinese created as part of a proposal in the Eighth Five-year Plan of China. It is similar to Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, but with notable divergences. The third edition has entries for 12,000 characters and 72,000 words, with over 80,000 example usages.

Strokes are the most basic writing units of Chinese characters. Stroke-based sorting, also called stroke-based ordering or stroke-based order, is one of the five sorting methods frequently used in modern Chinese dictionaries, the others being radical-based sorting, pinyin-based sorting, bopomofo and the four-corner method. In addition to functioning as an independent sorting method, stroke-based sorting is often employed to support the other methods. For example, in Xinhua Dictionary (新华字典), Xiandai Hanyu Cidian (现代汉语词典) and Oxford Chinese Dictionary, stroke-based sorting is used to sort homophones in Pinyin sorting, while in radical-based sorting it helps to sort the radical list, the characters under a common radical, as well as the list of characters difficult to lookup by radicals.

The GB stroke-based order, full name GB13000.1 Character Set Chinese Character Order , is a standard released by the National Language Commission of China in 1999. It is the current national standard for stroke-based sorting, and has been applied to the arrangement of the List of Commonly-used Standard Chinese Characters (通用规范汉字表), and the new versions of Xinhua Zidian and Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, etc.

Chinese character order, or Chinese character indexing, Chinese character collation and Chinese character sorting, is the way in which a Chinese character set is sorted into a sequence for the convenience of information retrieval. It may also refer to the sequence so produced. English dictionaries and indexes are normally arranged in alphabetical order for quick lookup. But Chinese is written in tens of thousands of different characters, not just dozens of letters in an alphabet, and that makes the sorting job much more challenging.

Grand Chinese Dictionary may refer to:

A Chinese character set is a group of Chinese characters. Since the size of a set is the number of elements in it, an introduction to Chinese character sets will also introduce the Chinese character numbers in them.