Boy Scouts of America et al. v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court, decided on June 28, 2000, that held that the constitutional right to freedom of association allowed the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) to exclude a homosexual person from membership in spite of a state law requiring equal treatment of homosexuals in public accommodations. More generally, the court ruled that a private organization such as the BSA may exclude a person from membership when "the presence of that person affects in a significant way the group's ability to advocate public or private viewpoints". In a five to four decision, the Supreme Court ruled that opposition to homosexuality is part of BSA's "expressive message" and that allowing homosexuals as adult leaders would interfere with that message.

Christian Legal Society (CLS) is a non-profit organization of Christian lawyers, judges, law professors, and law students. Its members profess to follow the "commandment of Jesus" to "seek justice with the love of God."

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline membership based on certain criteria. It can be described as the right of a person coming together with other individuals to collectively express, promote, pursue and/or defend common interests. Freedom of association is both an individual right and a collective right, guaranteed by all modern and democratic legal systems, including the United States Bill of Rights, article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights, section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and international law, including articles 20 and 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 22 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work by the International Labour Organization also ensures these rights.

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that sanctions of criminal punishment for those who commit sodomy are unconstitutional. The Court reaffirmed the concept of a "right to privacy" that earlier cases, such as Roe v. Wade, had found the U.S. Constitution provides, even though it is not explicitly enumerated. The Court based its ruling on the notions of personal autonomy to define one's own relationships and of American traditions of non-interference with private sexual decisions between consenting adults.

Anti-discrimination law or non-discrimination law refers to legislation designed to prevent discrimination against particular groups of people; these groups are often referred to as protected groups or protected classes. Anti-discrimination laws vary by jurisdiction with regard to the types of discrimination that are prohibited, and also the groups that are protected by that legislation. Commonly, these types of legislation are designed to prevent discrimination in employment, housing, education, and other areas of social life, such as public accommodations. Anti-discrimination law may include protections for groups based on sex, age, race, ethnicity, nationality, disability, mental illness or ability, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity/expression, sex characteristics, religion, creed, or individual political opinions.

Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States struck down both a state statute denying funding for education of undocumented immigrant children in the United States and a municipal school district's attempt to charge an annual $1,000 tuition fee for each student to compensate for lost state funding. The Court found that any state restriction imposed on the rights afforded to children based on their immigration status must be examined under a rational basis standard to determine whether it furthers a substantial government interest.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in the United States have increased significantly over time, and are socially liberal relative to most other nations. However, LGBT people in the U.S. may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Until 1962, all 50 states criminalized same-sex sexual activity, but by 2003 all remaining laws against same-sex sexual activity had been invalidated. Beginning with Massachusetts in 2004, LGBT Americans had won the right to marry in all 50 states by 2015. Additionally, in many states and municipalities, LGBT Americans are explicitly protected from discrimination in employment, housing, and access to public accommodations. However, in 2022, more than 300 bills have been introduced or passed in 36 states to restrict the rights of LGBT people.

Diane Pamela Wood is an American attorney and jurist who serves as a United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School.

Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995), was an opinion by the Supreme Court of the United States regarding whether a state university might, consistent with the First Amendment, withhold from student religious publications funding provided to similar secular student publications. The University of Virginia provided funding to every student organization that met funding-eligibility criteria, which Wide Awake, the student religious publication, fulfilled. The university's defense claimed that denying student activity funding of the religious magazine was necessary to avoid the University's violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The Koala is a satirical comedy college paper. In its current form, it exists as two unaffiliated publications, with one primarily distributed quarterly on the campus of University of California San Diego, and monthly on the campus of San Diego State University. The publication at UCSD was one of a handful of campus newspapers partly or entirely funded by the Associated Students of UCSD, until a decision by AS UCSD to defund all 13 student media outlets. The paper still exists as a registered student organization. SDSU's branch of The Koala at one point operated within SDSU Associated Students as a Recognized Student Organization (RSO) until that status was revoked in 2007. The original branch of The Koala was founded at UCSD in 1982, but the details of its origins are uncertain. The composition of the paper consists of artwork, articles, personals, and lists similar to David Letterman's Top Ten List. The Koala's standing protocol when giving interviews to commercial media of any sort is that no statement can be given until they are furnished with beer from the interviewing entity. Exceptions are made for student media as a matter of courtesy.Therefore, it does give an insight into the live of a Koala, but does butify the situation as well.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Botswana may face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBT citizens. Both female and male same-sex sexual acts have been legal in Botswana since 11 June 2019 after a unanimous ruling by the High Court of Botswana. Despite an appeal by the government, the ruling was upheld by the Botswana Court of Appeal on 29 November 2021.

The National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR) is a non-profit, public interest law firm in the United States that advocates for equitable public policies affecting the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, provides free legal assistance to LGBT clients and their legal advocates, and conducts community education on LGBT legal issues. It is headquartered in San Francisco with a policy team in Washington, DC. It is the only organization in the United States dedicated to lesbian legal issues, and the largest national lesbian organization in terms of members.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Ohio may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Ohio, and same-sex marriage has been legally recognized since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. Ohio statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBT people is illegal in 2020. In addition, a number of Ohio cities have passed anti-discrimination ordinances providing protections in housing and public accommodations. Conversion therapy is also banned in a number of cities. In December 2020, a federal judge invalidated a law banning sex changes on an individual's birth certificate within Ohio.

Hollingsworth v. Perry was a series of United States federal court cases that re-legalized same-sex marriage in the state of California. The case began in 2009 in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which found that banning same-sex marriage violates equal protection under the law. This decision overturned ballot initiative Proposition 8, which had banned same-sex marriage. After the State of California refused to defend Proposition 8, the official sponsors of Proposition 8 intervened and appealed to the Supreme Court. The case was litigated during the governorships of both Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jerry Brown, and was thus known as Perry v. Schwarzenegger and Perry v. Brown, respectively. As Hollingsworth v. Perry, it eventually reached the United States Supreme Court, which held that, in line with prior precedent, the official sponsors of a ballot initiative measure did not have Article III standing to appeal an adverse federal court ruling when the state refused to do so.

LGBT residents in the U.S. state of Georgia enjoy most of the same rights and liberties as non-LGBT Georgians. LGBT rights in the state have been a recent occurrence, with most improvements occurring from the 2010s onward. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1998, and same-sex marriage has been legal since 2015. In addition, the state's largest city Atlanta, has a vibrant LGBT community and holds the biggest Pride parade in the Southeast. The state's hate crime laws, effective since June 26, 2020, explicitly include sexual orientation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Texas face some legal and social challenges not faced by other people. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in the state in 2003 by the Lawrence v. Texas ruling. On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled bans on same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional in Obergefell v. Hodges. Texas has a hate crime statute that strengthens penalties for certain crimes motivated by a victim's sexual orientation, although it is rarely invoked. Gender identity is not included in the hate crime law. Even though federal law prohibits employment discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, there is no statewide law banning anti-LGBT discrimination. However, some localities in Texas have ordinances that provide a variety of legal protections and benefits to LGBT people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the United States state of Virginia enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT persons. LGBT rights in the state are a recent occurrence, with most improvements in LGBT rights occurring in the 2000s and 2010s. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Virginia since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Bostic v. Rainey. Effective since July 1, 2020, there is a statewide law protecting LGBT persons from discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and credit. The state's hate crime laws effective since July 1, 2020, now explicitly include both sexual orientation and gender identity.

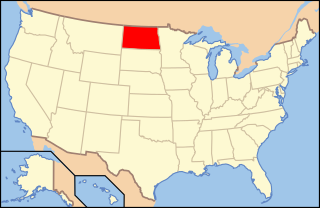

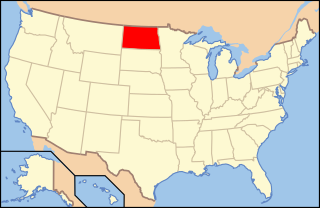

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of North Dakota may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in North Dakota, and same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples; same-sex marriage has been legal since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. State statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBT people is illegal under federal law.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. commonwealth of Kentucky have most of the same rights as non-LGBT persons have, but still face some legal challenges not experienced by other people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Kentucky. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. On February 12, 2014, a federal judge ruled that the state must recognize same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions, but the ruling was put on hold pending review by the Sixth Circuit. Same sex-marriage is now legal in the state under the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. The decision, which struck down Kentucky's statutory and constitutional bans on same-sex marriages, and all other same sex marriage bans elsewhere in the country, was handed down on June 26, 2015.