The yellow crazy ant, also known as the long-legged ant or Maldive ant, is a species of ant, thought to be native to West Africa or Asia. They have been accidentally introduced to numerous places in the world's tropics.

The Jefferson salamander is a mole salamander native to the northeastern United States, southern and central Ontario, and southwestern Quebec. It was named after Jefferson College in Pennsylvania.

The Mexican burrowing toad is the single living representative of the family Rhinophrynidae. It is a unique species in its taxonomy and morphology, with special adaptations to assist them in digging burrows where they spend most of their time. These adaptations include a small pointed snout and face, keratinized structures and a lack of webbing on front limbs, and specialized tongue morphology to assist in feeding on ants and termites underground. The body is nearly equal in width and length. It is a dark brown to black color with a red-orange stripe on its back along with splotches of color on its body. The generic name Rhinophrynus means 'nose-toad', from rhino- (ῥῑνο-), the combining form of the Ancient Greek rhis and phrunē.

Abbott's booby is an endangered seabird of the sulid family, which includes gannets and boobies. It is a large booby and is placed within its own monotypic genus. It was first identified from a specimen collected by William Louis Abbott, who discovered it on Assumption Island in 1892.

Gecarcoidea lalandii is a large species of terrestrial crab. It is dark purple in colour, with long legs and short pincers. It is nocturnal, so spends most of the day hiding in burrows. Compared to the related G. natalis, G. lalandii is relatively widespread, being found in the Indo-Pacific from the Andaman Islands and eastwards. Adults mainly occur in forest, but can sometimes be found in more open habitats. When carrying eggs, females migrate to the coast, where they release the eggs in the tidal zone. Small adults sometimes fall prey to the crab Geograpsus crinipes.

Animal migration is the relatively long-distance movement of individual animals, usually on a seasonal basis. It is the most common form of migration in ecology. It is found in all major animal groups, including birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, insects, and crustaceans. The cause of migration may be local climate, local availability of food, the season of the year or for mating.

The Christmas boobook, also known more specifically as the Christmas Island hawk-owl, is a species of owl in the family Strigidae.

The Christmas white-eye is a species of bird in the family Zosteropidae. It is endemic to Christmas Island. Its natural habitats are tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests and subtropical or tropical moist shrubland. It is threatened by habitat destruction.

The Christmas Island shrew, also known as the Christmas Island musk-shrew is an extremely rare or possibly extinct shrew from Christmas Island. It was variously placed as subspecies of the Asian gray shrew or the Southeast Asian shrew, but morphological differences and the large distance between the species indicate that it is an entirely distinct species.

Christmas Island National Park is a national park occupying most of Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean southwest of Indonesia. The park is home to many species of animal and plant life, including the eponymous red crab, whose annual migration sees around 100 million crabs move to the sea to spawn. Christmas Island is the only nesting place for the endangered Abbott's booby and critically endangered Christmas Island frigatebird, and the wide range of other endemic species makes the island of significant interest to the scientific community.

The Christmas goshawk or Christmas Island goshawk is a bird of prey in the goshawk and sparrowhawk family Accipitridae. It is a threatened endemic of Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the eastern Indian Ocean.

The coconut crab is a terrestrial species of giant hermit crab, and is also known as the robber crab or palm thief. It is the largest terrestrial arthropod known, with a weight of up to 4.1 kg (9 lb). The distance from the tip of one leg to the tip of another can be as wide as 1 m. It is found on islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, as far east as the Gambier Islands, Pitcairn Islands and Caroline Island and as far south as Zanzibar. While its range broadly shadows the distribution of the coconut palm, the coconut crab has been extirpated from most areas with a significant human population such as mainland Australia and Madagascar.

Gecarcinus ruricola is a species of terrestrial crab. It is the most terrestrial of the Caribbean land crabs, and is found from western Cuba across the Antilles as far east as Barbados. Common names for G. ruricola include the purple land crab, black land crab, red land crab, and zombie crab.

Johngarthia lagostoma is a species of terrestrial crab that lives on Ascension Island and three other islands in the South Atlantic. It grows to a carapace width of 110 mm (4.3 in) on Ascension Island, where it is the largest native land animal. It exists in two distinct colour morphs, one yellow and one purple, with few intermediates. The yellow morph dominates on Ascension Island, while the purple morph is more frequent on Rocas Atoll. The species differs from other Johngarthia species by the form of the third maxilliped.

A number of lineages of crabs are designed to live predominantly on land. Examples of terrestrial crabs are found in the families Gecarcinidae and Gecarcinucidae, as well as in selected genera from other families, such as Sesarma, although the term "land crab" is often used to mean solely the family Gecarcinidae.

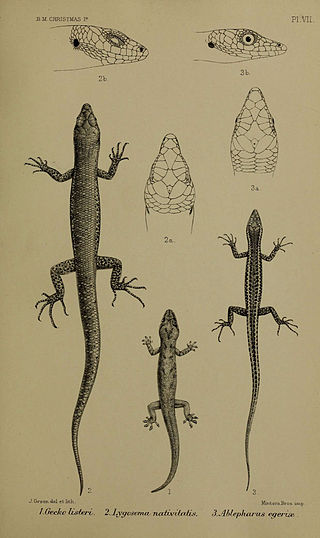

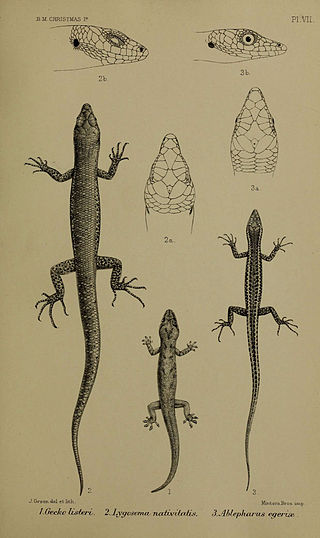

Cryptoblepharus egeriae, also known commonly as the blue-tailed shinning-skink, the Christmas Island blue-tailed shinning-skink, and the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae that was once endemic to Christmas Island. The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink was discovered in 1888. It was formerly the most abundant reptile on the island, and occurred in high numbers particularly near the human settlement. However, the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink began to decline sharply outwardly from the human settlement by the early 1990s, which coincided with the introduction of a predatory snake and also followed the introduction of the yellow crazy ant in the mid-1980s. By 2006, the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink was on the endangered animals list, and by 2010 the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink was extinct in the wild. From 2009 to 2010, Parks Australia and Taronga Zoo started a captive breeding program, which has prevented total extinction of the species.

Migration, in ecology, is the large-scale movement of members of a species to a different environment. Migration is a natural behavior and component of the life cycle of many species of mobile organisms, not limited to animals, though animal migration is the best known type. Migration is often cyclical, frequently occurring on a seasonal basis, and in some cases on a daily basis. Species migrate to take advantage of more favorable conditions with respect to food availability, safety from predation, mating opportunity, or other environmental factors.

The wildlife of Christmas Island is composed of the flora and fauna of this isolated island in the tropical Indian Ocean. Christmas Island is the summit plateau of an underwater volcano. It is mostly clad in tropical rainforest and has karst, cliffs, wetlands, coasts and sea. It is a small island with a land area of 135 km2 (52 sq mi), 63% of which has been declared a National park. Most of the rainforest remains intact and supports a large range of endemic species of animals and plants.

The Christmas and Cocos Islands tropical forests ecoregion covers forested areas of Christmas Island and North Keeling Island, two small seamount islands south of the Indonesian island of Java. The forests of these two islands share tree species of the Indo-Pacific and Melanesian types on nearby islands, the forests of Christmas Island and North Keeling Island are unique in how they reflect the effects of large populations of terrestrial red crabs. Because of the remoteness of the islands, there are many endemic species.

The annual migration of red crabs in Australia begins in October/November each year. Millions of red crabs Gecarcoidea natalis migrate from the Australian islands to the Indian Ocean during this one to two-week-long period. The purpose of migration is to go underwater and lay eggs and breeding has to be made possible. During this migration season, the routes of arrival and departure of crabs are closed with barriers so that they can be protected from any kind of damage.