Migraine is a genetically influenced complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may include vomiting, cognitive dysfunction, allodynia, and dizziness. Exacerbation of headache symptoms during physical activity is another distinguishing feature. Up to one-third of migraine sufferers experience aura, a premonitory period of sensory disturbance widely accepted to be caused by cortical spreading depression at the onset of a migraine attack. Although primarily considered to be a headache disorder, migraine is highly heterogenous in its clinical presentation and is better thought of as a spectrum disease rather than a distinct clinical entity. Disease burden can range from episodic discrete attacks, consisting of as little as several lifetime attacks, to chronic disease.

Headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Cluster headache is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent severe headaches on one side of the head, typically around the eye(s). There is often accompanying eye watering, nasal congestion, or swelling around the eye on the affected side. These symptoms typically last 15 minutes to 3 hours. Attacks often occur in clusters which typically last for weeks or months and occasionally more than a year.

A medication overuse headache (MOH), also known as a rebound headache, usually occurs when painkillers are taken frequently to relieve headaches. These cases are often referred to as painkiller headaches. Rebound headaches frequently occur daily, can be very painful and are a common cause of chronic daily headache. They typically occur in patients with an underlying headache disorder such as migraine or tension-type headache that "transforms" over time from an episodic condition to chronic daily headache due to excessive intake of acute headache relief medications. MOH is a serious, disabling and well-characterized disorder, which represents a worldwide problem and is now considered the third-most prevalent type of headache. The proportion of patients in the population with Chronic Daily Headache (CDH) who overuse acute medications ranges from 18% to 33%. The prevalence of medication overuse headache (MOH) varies depending on the population studied and diagnostic criteria used. However, it is estimated that MOH affects approximately 1-2% of the general population, but its relative frequency is much higher in secondary and tertiary care.

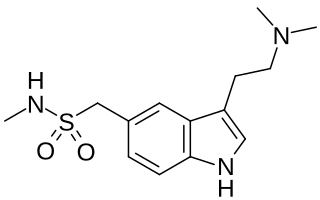

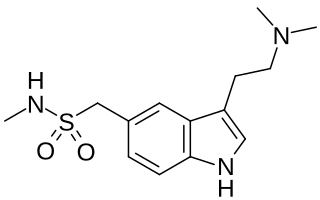

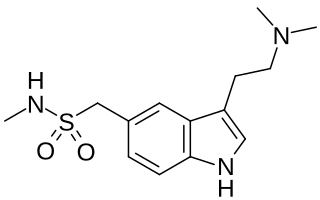

Sumatriptan, sold under the brand name Imitrex among others, is a medication used to treat migraine headaches and cluster headaches. It is taken orally, intranasally, or by subcutaneous injection. Therapeutic effects generally occur within three hours.

A headache is often present in patients with epilepsy. If the headache occurs in the vicinity of a seizure, it is defined as peri-ictal headache, which can occur either before (pre-ictal) or after (post-ictal) the seizure, to which the term ictal refers. An ictal headache itself may or may not be an epileptic manifestation. In the first case it is defined as ictal epileptic headache or simply epileptic headache. It is a real painful seizure, that can remain isolated or be followed by other manifestations of the seizure. On the other hand, the ictal non-epileptic headache is a headache that occurs during a seizure but it is not due to an epileptic mechanism. When the headache does not occur in the vicinity of a seizure it is defined as inter-ictal headache. In this case it is a disorder autonomous from epilepsy, that is a comorbidity.

Triptans are a family of tryptamine-based drugs used as abortive medication in the treatment of migraines and cluster headaches. This drug class was first commercially introduced in the 1990s. While effective at treating individual headaches, they do not provide preventive treatment and are not considered a cure. They are not effective for the treatment of tension–type headache, except in persons who also experience migraines. Triptans do not relieve other kinds of pain.

Indometacin, also known as indomethacin, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) commonly used as a prescription medication to reduce fever, pain, stiffness, and swelling from inflammation. It works by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, endogenous signaling molecules known to cause these symptoms. It does this by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, an enzyme that catalyzes the production of prostaglandins.

Sexual headache is a type of headache that occurs in the skull and neck during sexual activity, including masturbation or orgasm. These headaches are usually benign, but occasionally are caused by intracranial hemorrhage and cerebral infarction, especially if the pain is sudden and severe. They may be caused by general exertion, sexual excitement, or contraction of the neck and facial muscles. Most cases can be successfully treated with medication.

Hemicrania continua (HC) is a persistent unilateral headache that responds to indomethacin. It is usually unremitting, but rare cases of remission have been documented. Hemicrania continua is considered a primary headache disorder, meaning that another condition does not cause it.

Main article: Management of migraine

Hypnic headaches are benign primary headaches that affect the elderly, with an average age of onset at 63 ± 11 years. They are moderate, throbbing, bilateral or unilateral headaches that wake the sufferer from sleep once or multiple times a night. They typically begin a few hours after sleep begins and can last from 15–180 min. There is normally no nausea, photophobia, phonophobia or autonomic symptoms associated with the headache. They commonly occur at the same time every night possibly linking the headaches with circadian rhythm, but polysomnography has recently revealed that the onset of hypnic headaches may be associated with REM sleep.

Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. Since Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent, benign (non-cancerous), aseptic meningitis, it is also referred to as benign recurrent lymphocytic meningitis. It was named for Pierre Mollaret, the French neurologist who first described it in 1944.

New daily persistent headache (NDPH) is a primary headache syndrome which can mimic chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache. The headache is daily and unremitting from very soon after onset, usually in a person who does not have a history of a primary headache disorder. The pain can be intermittent, but lasts more than 3 months. Headache onset is abrupt and people often remember the date, circumstance and, occasionally, the time of headache onset. One retrospective study stated that over 80% of patients could state the exact date their headache began.

Vestibular migraine (VM) is vertigo with migraine, either as a symptom of migraine or as a related neurological disorder.

Main article: Management of migraine

Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing is a rare headache disorder that belongs to the group of headaches called trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TACs). Symptoms include excruciating burning, stabbing, or electrical headaches mainly near the eye and typically these sensations are only on one side of the body. The headache attacks are typically accompanied by cranial autonomic signs that are unique to SUNCT. Each attack can last from five seconds to six minutes and may occur up to 200 times daily.

Abdominal migraine(AM) is a functional disorder that usually manifests in childhood and adolescence, without a clear pathologic mechanism or biochemical irregularity. Children frequently experience sporadic episodes of excruciating central abdominal pain accompanied by migrainous symptoms like nausea, vomiting, severe headaches, and general pallor. Abdominal migraine can be diagnosed based on clinical criteria and the exclusion of other disorders.

Occipital nerve stimulation (ONS), also called peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) of the occipital nerves, is used to treat chronic migraine patients who have failed to respond to pharmaceutical treatments.

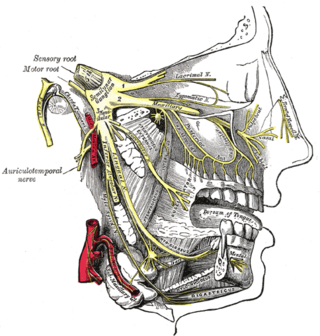

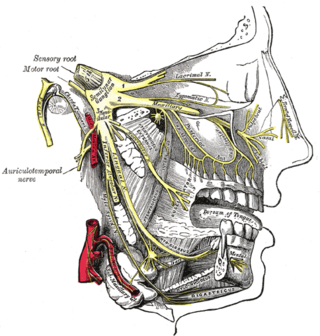

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TAC) refers to a group of primary headaches that occurs with pain on one side of the head in the trigeminal nerve area and symptoms in autonomic systems on the same side, such as eye watering and redness or drooping eyelids.