In Christianity, ablution is a prescribed washing of part or all of the body or possessions, such as clothing or ceremonial objects, with the intent of purification or dedication. In Christianity, both baptism and footwashing are forms of ablution. Prior to praying the canonical hours at seven fixed prayer times, Oriental Orthodox Christians wash their hands and face. In liturgical churches, ablution can refer to purifying fingers or vessels related to the Eucharist. In the New Testament, washing also occurs in reference to rites of Judaism part of the action of a healing by Jesus, the preparation of a body for burial, the washing of nets by fishermen, a person's personal washing of the face to appear in public, the cleansing of an injured person's wounds, Pontius Pilate's washing of his hands as a symbolic claim of innocence and foot washing, which is a rite within the Christian Churches. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Pontius Pilate declared himself innocent of the blood of Jesus by washing his hands. This act of Pilate may not, however, have been borrowed from the custom of the Jews. The same practice was common among the Greeks and Romans.

The epiclesis refers to the invocation of one or several gods. In ancient Greek religion, the epiclesis was the epithet used as the surname given to a deity in religious contexts. The term was borrowed into the Christian tradition, where it designates the part of the Anaphora by which the priest invokes the Holy Spirit upon the Eucharistic bread and wine in some Christian churches. In most Eastern Christian traditions, the Epiclesis comes after the Anamnesis ; in the Western Rite it usually precedes. In the historic practice of the Western Christian Churches, the consecration is effected at the Words of Institution though during the rise of the Liturgical Movement, many denominations introduced an explicit epiclesis in their liturgies.

Ritual purification is a ritual prescribed by a religion through which a person is considered to be freed of uncleanliness, especially prior to the worship of a deity, and ritual purity is a state of ritual cleanliness. Ritual purification may also apply to objects and places. Ritual uncleanliness is not identical with ordinary physical impurity, such as dirt stains; nevertheless, body fluids are generally considered ritually unclean.

Holy water is water that has been blessed by a member of the clergy or a religious figure, or derived from a well or spring considered holy. The use for cleansing prior to a baptism and spiritual cleansing is common in several religions, from Christianity to Sikhism. The use of holy water as a sacramental for protection against evil is common among Lutherans, Anglicans, Roman Catholics, and Eastern Christians.

The Presentation of Jesus is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem. It is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas, or the "Feast of the Presentation of Jesus". The episode is described in chapter 2 of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament. Within the account, "Luke's narration of the Presentation in the Temple combines the purification rite with the Jewish ceremony of the redemption of the firstborn ."

Consecration is the transfer of a person or a thing to the sacred sphere for a special purpose or service. The word consecration literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different groups. The origin of the word comes from the Latin stem consecrat, which means dedicated, devoted, and sacred. A synonym for consecration is sanctification; its antonym is desecration.

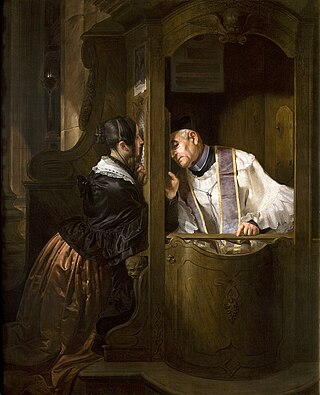

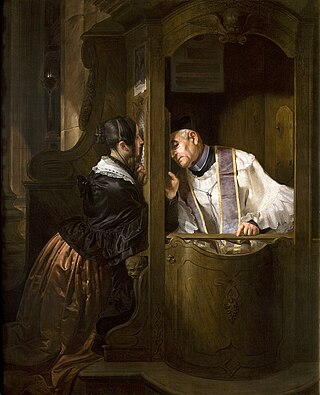

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the practice of absolution vary between Christian denominations.

"Alma Redemptoris Mater" is a Marian hymn, written in Latin hexameter, and one of four seasonal liturgical Marian antiphons sung at the end of the office of Compline.

A grace is a short prayer or thankful phrase said before or after eating. The term most commonly refers to Christian traditions. Some traditions hold that grace and thanksgiving imparts a blessing which sanctifies the meal. In English, reciting such a prayer is sometimes referred to as "saying grace". The term comes from the Ecclesiastical Latin phrase gratiarum actio, "act of thanks." Theologically, the act of saying grace is derived from the Bible, in which Jesus and Saint Paul pray before meals. The practice reflects the belief that humans should thank God who is believed to be the origin of everything.

Antiochene Rite also known as Antiochian Rite refers to the family of liturgies originally used by the patriarch of Antioch.

The Euchologion is one of the chief liturgical books of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches, containing the portions of the services which are said by the bishop, priest, or deacon. The Euchologion roughly corresponds to a combination of the missal, ritual, and pontifical as they are used in Latin liturgical rites. There are several different volumes of the book in use.

Thanksgiving after Communion is a spiritual practice among Christians who believe in the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Communion bread, maintaining themselves in prayer for some time to thank God and especially listening in their hearts for guidance from their Divine guest. This practice was and is highly recommended by saints, theologians, and Doctors of the Church.

Good Friday Prayer can refer to any of the prayers prayed by Christians on Good Friday, the Friday before Easter, or to all such prayers collectively.

The entrance prayers are the prayers recited by the deacon and priest upon entering the temple before celebrating the Divine Liturgy in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite.

Absolution of the dead is a prayer for or a declaration of absolution of a dead person's sins that takes place at the person's religious funeral.

Among Eastern Orthodox and Eastern-Rite Catholic Christians, holy water is blessed in the church and given to the faithful to drink at home when needed and to bless their homes. In the weeks following the Feast of Epiphany, clergy visit the homes of parishioners and conduct a service of blessing by using the holy water that was blessed on the Feast of Theophany. For baptism, the water is sanctified with a special blessing.

Blessed salt has been used in various forms throughout the history of Christianity. Among early Christians, the savoring of blessed salt often took place along with baptism. In the fourth century, Augustine of Hippo named these practices "visible forms of invisible grace". However, its modern use as a sacramental remains mostly limited to its use with holy water within the Anglican Communion and Roman Catholic Church.

Impurity after childbirth is the concept in many cultures and religions that a new mother is in a state of uncleanliness for a period of time after childbirth, requiring ritual purification. Practices vary, but typically there are limits around what she can touch, who she can interact with, where she can go, and what tasks she can do. Some practices related to impurity after childbirth, such as seclusion, overlap with the more general practice of postpartum confinement.

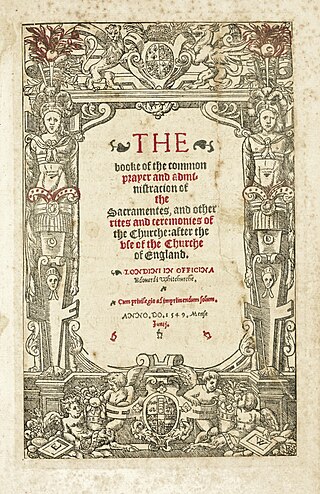

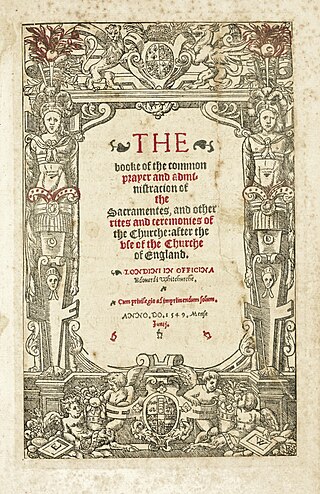

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer, variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by the significantly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

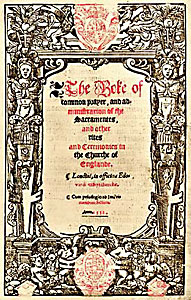

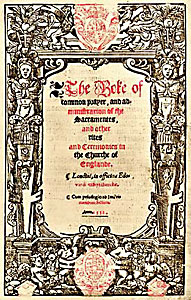

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was the second version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) and contained the official liturgy of the Church of England from November 1552 until July 1553. The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services. The 1552 prayer book was revised to be explicitly Reformed in its theology.