The Circus Maximus is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 621 m (2,037 ft) in length and 118 m (387 ft) in width and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The Campus Martius was a publicly owned area of ancient Rome about 2 square kilometres in extent. In the Middle Ages, it was the most populous area of Rome. The IV rione of Rome, Campo Marzio, which covers a smaller section of the original area, bears the same name.

The Forma Urbis Romae or Severan Marble Plan is a massive marble map of ancient Rome, created under the emperor Septimius Severus between 203 and 211 CE. Matteo Cadario gives specific years of 205–208, noting that the map was based on property records.

The Secular or Saecular Games was an ancient Roman religious celebration involving sacrifices, theatrical performances, and public games. It was held irregularly in Rome for three days and nights to mark the ends of various eras and to celebrate the beginning of the next. In particular, the Romans reckoned a saeculum as the longest possible length of human life, either 100 or 110 years in length; as such, it was used to mark various centennials, particularly anniversaries from the computed founding of Rome.

Trajan's Forum was the last of the Imperial fora to be constructed in ancient Rome. The architect Apollodorus of Damascus oversaw its construction.

In 7 BC, Augustus divided the city of Rome into 14 administrative regions. These replaced the four regiones—or "quarters"—traditionally attributed to Servius Tullius, sixth king of Rome. They were further divided into official neighborhoods.

Andrea Carandini is an Italian professor of archaeology specialising in ancient Rome. Among his many excavations is the villa of Settefinestre.

The Porticus Octaviae is an ancient structure in Rome. The colonnaded walks of the portico enclosed the Temples of Juno Regina (north) and Jupiter Stator (south), as well as a library. The structure was used as a fish market from the medieval period up to the end of the 19th century.

The Temple of Apollo Sosianus is a Roman temple dedicated to Apollo in the Campus Martius, next to the Theatre of Marcellus and the Porticus Octaviae, in Rome, Italy. Its present name derives from that of its final rebuilder, Gaius Sosius.

The Temple of Janus at the Forum Holitorium was a Roman temple dedicated to the god Janus, located between the Capitoline Hill and the Tiber River near the Circus Flaminius in the southern Campus Martius. The temple was built during the First Punic War, after the Temple of Janus in the Roman Forum.

The Temple of Bellona was an temple dedicated to the goddess of war Bellona in ancient Rome. It was located at the northern end of the Forum Olitorium, the Roman vegetable market, near the Carmental Gate. The Temple of Apollo Sosianus and the Theater of Marcellus were located nearby.

During the Middle Ages, Rome was divided into a number of administrative regions, usually numbering between twelve and fourteen, which changed over time.

The trigarium was an equestrian training ground in the northwest corner of the Campus Martius in ancient Rome. Its name was taken from the triga, a three-horse chariot.

The coRBINis good were games (ludi) held in ancient Rome in honor of the di inferi, the gods of the underworld. They were not part of a regularly scheduled religious festival on the calendar, but were held as expiatory rites religionis causa, occasioned by religious concerns.

The Temple of Claudius, also variously known as the Temple of the Divus Claudius, the Temple of the Divine Claudius, the Temple of the Deified Claudius, or in an abbreviated form as the Claudium, was an ancient structure that covered a large area of the Caelian Hill in Rome, Italy. It housed the Imperial cult of the Emperor Claudius, who was deified after his death in 54 AD.

The Temple of Hercules Musarum was a Roman temple dedicated to Hercules Musarum located near the Circus Flaminius in the southern Campus Martius in ancient Rome.

The Temple of Juno Regina was a temple dedicated to the Roman goddess Juno Regina located near the Circus Flaminius in the southern Campus Martius of ancient Rome. It was solemnly vowed by the consul Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in 187 BC during his final battle against the Liguri and was consecrated and opened on 23 December 179 BC, while he was serving as censor. It was linked by a portico to a temple of Fortuna, possibly the Temple of Fortuna Equestris, and later joined by a temple of Jupiter Stator. Both temples were surrounded by the Portico of Metellus. The portico and both temples were rebuilt by Augustus as the Porticus Octaviae sometime after 27 BC.

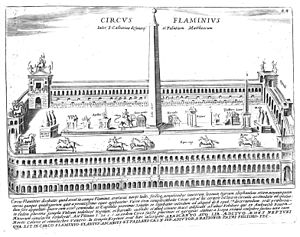

The Regio IX Circus Flaminius is the ninth regio of imperial Rome, under Augustus's administrative reform. Regio IX took its name from the racecourse located in the southern end of the Campus Martius, close to Tiber Island.

The Arch of Germanicus was an arch of Rome situated at the northern end of the Circus Flaminius.