A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines a forest as, "Land spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ. It does not include land that is predominantly under agricultural or urban use." Using this definition, Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 found that forests covered 4.06 billion hectares, or approximately 31 percent of the world's land area in 2020.

Reforestation is the natural or intentional restocking of existing forests and woodlands (forestation) that have been depleted, usually through deforestation but also after clearcutting. Two important purposes of reforestation programs are for harvesting of wood or for climate change mitigation purposes.

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars. In forestry, the term logging is sometimes used narrowly to describe the logistics of moving wood from the stump to somewhere outside the forest, usually a sawmill or a lumber yard. In common usage, however, the term may cover a range of forestry or silviculture activities.

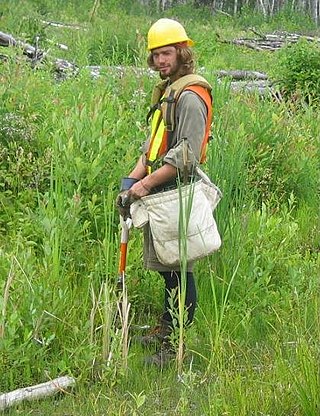

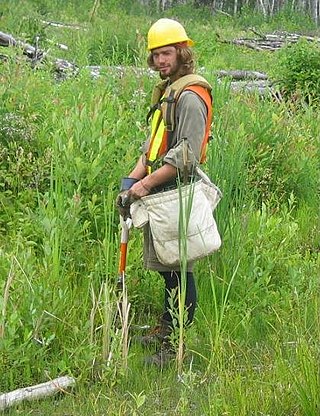

Tree planting is the process of transplanting tree seedlings, generally for forestry, land reclamation, or landscaping purposes. It differs from the transplantation of larger trees in arboriculture and from the lower-cost but slower and less reliable distribution of tree seeds. Trees contribute to their environment over long periods of time by providing oxygen, improving air quality, climate amelioration, conserving water, preserving soil, and supporting wildlife. During the process of photosynthesis, trees take in carbon dioxide and produce the oxygen we breathe.

Silviculture is the practice of controlling the growth, composition/structure, as well as quality of forests to meet values and needs, specifically timber production.

Clearcutting, clearfelling or clearcut logging is a forestry/logging practice in which most or all trees in an area are uniformly cut down. Along with shelterwood and seed tree harvests, it is used by foresters to create certain types of forest ecosystems and to promote select species that require an abundance of sunlight or grow in large, even-age stands. Logging companies and forest-worker unions in some countries support the practice for scientific, safety and economic reasons, while detractors consider it a form of deforestation that destroys natural habitats and contributes to climate change. Environmentalists, traditional owners, local residents and others have regularly campaigned against clearcutting, including through the use of blockades and nonviolent direct action.

Articles on forestry topics include:.

Selection cutting, also known as selection system, is the silvicultural practice of harvesting trees in a way that moves a forest stand towards an uneven-aged or all-aged condition, or 'structure'. Using stocking models derived from the study of old growth forests, selection cutting, also known as 'selection system', or 'selection silviculture', manages the establishment, continued growth and final harvest of multiple age classes of trees within a stand. A closely related approach to forest management is Continuous Cover Forestry (CCF), which makes use of selection systems to achieve a permanently irregular stand structure.

Farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) is a low-cost, sustainable land restoration technique used to combat poverty and hunger amongst poor subsistence farmers in developing countries by increasing food and timber production, and resilience to climate extremes. It involves the systematic regeneration and management of trees and shrubs from tree stumps, roots and seeds. FMNR was developed by the Australian agricultural economist Tony Rinaudo in the 1980s in West Africa. The background and development are described in Rinaudo's book The Forest Underground.

Variable retention is a relatively new silvicultural system that retains forest structural elements for at least one rotation in order to preserve environmental values associated with structurally complex forests.

Shelterwood cutting is the progression of forest cuttings leading to the establishment of a new generation of seedlings of a particular species or group of species without planting. This silvicultural system is normally implemented in forests that are considered mature, often after several thinnings. The desired species are usually long-lived and their seedlings would naturally tend to start under partial shade. The shelterwood system gives enough light for the desired species to establish without giving enough light for the weeds that are adapted to full sun. Once the desired species is established, subsequent cuttings give the new seedlings more light and the growing space is fully passed to the new generation.

Rates and causes of deforestation vary from region to region around the world. In 2009, two-thirds of the world's forests were located in just 10 countries: Russia, Brazil, Canada, the United States, China, Australia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, India, and Peru.

Even-aged timber management is a group of forest management practices employed to achieve a nearly coeval cohort group of forest trees. The practice of even-aged management is often pursued to minimize costs to loggers. In some cases, the practices of even aged timber management are frequently implicated in biodiversity loss and other ecological damage. Even-aged timber management can also be beneficial to restoring natural native species succession.

The Ancient Forest Alliance is a grassroots environmental organization in British Columbia, Canada. It was founded in January 2010, and is dedicated to protecting British Columbia's old-growth forests in areas where they are scarce, and ensuring sustainable forestry jobs in that province.

Gap dynamics refers to the pattern of plant growth that occurs following the creation of a forest gap, a local area of natural disturbance that results in an opening in the canopy of a forest. Gap dynamics are a typical characteristic of both temperate and tropical forests and have a wide variety of causes and effects on forest life.

The deforestation in British Columbia has occurred at a heavy rate during periods of the past, but with new sustainable efforts and programs the rate of deforestation is decreasing in the province. In British Columbia, forests cover over 55 million hectares, which is 57.9% of British Columbia's 95 million hectares of land. The forests are mainly composed of coniferous trees, such as pines, spruces and firs.

The Canadian forestry industry is a major contributor to the Canadian economy. With 39% of Canada's land acreage covered by forests, the country contains 9% of the world's forested land. The forests are made up primarily of spruce, poplar and pine. The Canadian forestry industry is composed of three main sectors: solid wood manufacturing, pulp and paper and logging. Forests, as well as forestry are managed by The Department of Natural Resources Canada and the Canadian Forest Service, in cooperation with several organizations which represent government groups, officials, policy experts, and numerous other stakeholders. Extensive deforestation by European settlers during the 18th and 19th centuries has been halted by more modern policies. Today, less than 1% of Canada's forests are affected by logging each year. Canada is the 2nd largest exporter of wood products, and produces 12.3% of the global market share. Economic concerns related to forestry include greenhouse gas emissions, biotechnology, biological diversity, and infestation by pests such as the mountain pine beetle.

Deforestation is a primary contributor to climate change, and climate change affects forests. Land use changes, especially in the form of deforestation, are the second largest anthropogenic source of atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions, after fossil fuel combustion. Greenhouse gases are emitted during combustion of forest biomass and decomposition of remaining plant material and soil carbon. Global models and national greenhouse gas inventories give similar results for deforestation emissions. As of 2019, deforestation is responsible for about 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon emissions from tropical deforestation are accelerating. Growing forests are a carbon sink with additional potential to mitigate the effects of climate change. Some of the effects of climate change, such as more wildfires, insect outbreaks, invasive species, and storms are factors that increase deforestation.

Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere Region (MABR) is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve located on the east coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. It was designated in 2000 by UNESCO to protect a large second-growth coast Douglas fir ecosystem in the watersheds of the Little Qualicum and Englishman Rivers from being developed.

The Maybeso Experimental Forest is an experimental forest on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. It is located near Hollis, Alaska within the Tongass National Forest and is administered by the United States Forest Service. The area of the forest is approximately 1,101 acres (446 ha), with a peak elevation of 2,953 feet (900 m). The forest was established in 1956 to examine the effects of large-scale clearcut timber harvesting on forest regeneration and anadromous salmonid spawning areas. The Maybeso Experimental Forest is the site of the first large-scale clearcut logging operation in Southeast Alaska, and nearly all commercial forest was removed from the area between 1953 and 1960. Presently, the forest is an even-aged, second-growth Sitka spruce and Western hemlock forest.