Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other social divisions such as in race, class, and sexual orientation. The ideology and movement emerged in the 1960s.

Womyn is one of several alternative political spellings of the English word women, used by some feminists. There are other spellings, including womban or womon (singular), and wombyn or wimmin (plural). Some writers who use such alternative spellings, avoiding the suffix "-man" or "-men", see them as an expression of female independence and a repudiation of traditions that define women by reference to a male norm. Recently, the term womxn has been used by intersectional feminists to indicate the same ideas while foregrounding or more explicitly including transgender women and women of color.

Afrocentrism is a worldview that centered on the history of people of African descent or a biased view that favors it over non-African civilizations. It is in some respects a response to Eurocentric attitudes about African people and their historical contributions. It seeks to counter what it sees as mistakes and ideas perpetuated by the racist philosophical underpinnings of Western academic disciplines as they developed during and since Europe's Early Renaissance as justifying rationales for the enslavement of other peoples, in order to enable more accurate accounts of not only African but all people's contributions to world history. Afrocentricity deals primarily with self-determination and African agency and is a pan-African point of view for the study of culture, philosophy, and history.

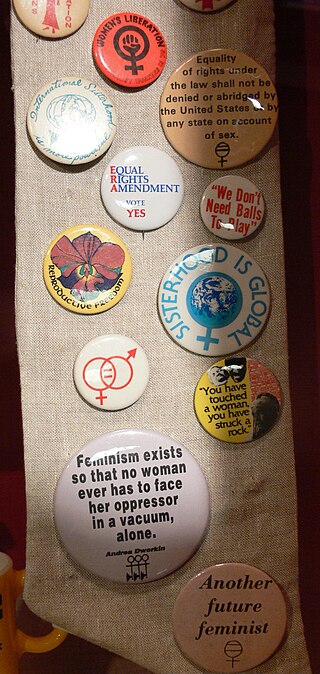

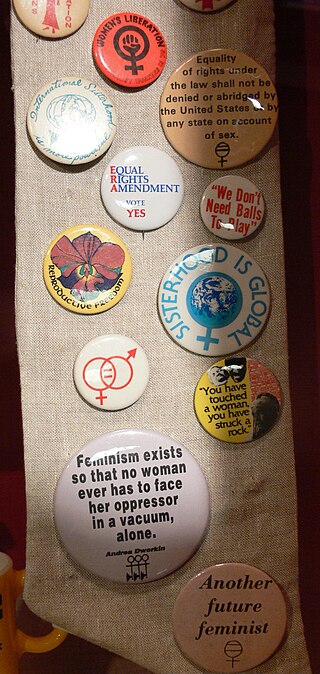

This is an index of articles related to the issue of feminism, women's liberation, the women's movement, and women's rights.

Postcolonial feminism is a form of feminism that developed as a response to feminism focusing solely on the experiences of women in Western cultures and former colonies. Postcolonial feminism seeks to account for the way that racism and the long-lasting political, economic, and cultural effects of colonialism affect non-white, non-Western women in the postcolonial world. Postcolonial feminism originated in the 1980s as a critique of feminist theorists in developed countries pointing out the universalizing tendencies of mainstream feminist ideas and argues that women living in non-Western countries are misrepresented.

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the logical result of feminism. Lesbian feminism was most influential in the 1970s and early 1980s, primarily in North America and Western Europe, but began in the late 1960s and arose out of dissatisfaction with the New Left, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, sexism within the gay liberation movement, and homophobia within popular women's movements at the time. Many of the supporters of Lesbianism were actually women involved in gay liberation who were tired of the sexism and centering of gay men within the community and lesbian women in the mainstream women's movement who were tired of the homophobia involved in it.

Womanism is a social theory based on the history and everyday experiences of black women. It seeks, according to womanist scholar Layli Maparyan (Phillips), to "restore the balance between people and the environment/nature and reconcil[e] human life with the spiritual dimension". Writer Alice Walker coined the term "womanist" in a short story, Coming Apart, in 1979. Since Walker's initial use, the term has evolved to envelop a spectrum of varied perspectives on the issues facing black women.

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences, interests, chores, and feminist politics in a variety of fields, such as anthropology and sociology, communication, media studies, psychoanalysis, political theory, home economics, literature, education, and philosophy.

Cultural feminism, the view that there is a "female nature" or "female essence", attempts to revalue and redefine attributes ascribed to femaleness. It is also used to describe theories that commend innate differences between women and men. Cultural feminism diverged from radical feminism, when some radical feminists rejected the previous feminist and patriarchal notion that feminine traits are undesirable and returned to an essentialist view of gender differences in which they regard female traits as superior.

Womanist theology is a methodological approach to theology which centers the experience and perspectives of Black women, particularly African-American women. The first generation of womanist theologians and ethicists began writing in the mid to late 1980s, and the field has since expanded significantly. The term has its roots in Alice Walker's writings on womanism. "Womanist theology" was first used in an article in 1987 by Delores S. Williams. Within Christian theological discourse, Womanist theology emerged as a corrective to early feminist theology written by white feminists that did not address the impact of race on women's lives, or take into account the realities faced by Black women within the United States. Similarly, womanist theologians highlighted the ways in which Black theology, written predominantly by male theologians, failed to consider the perspectives and insights of Black women. Scholars who espouse womanist theology are not monolithic nor do they adopt each aspect of Walker's definition. Yet, these scholars often find kinship in their anti-sexist, antiracist and anti-classist commitments to feminist and liberation theologies.

Afrocentricity is an academic theory and approach to scholarship that seeks to center the experiences and peoples of Africa and the African diaspora within their own historical, cultural, and sociological contexts. First developed as a systematized methodology by Molefi Kete Asante in 1980, he drew inspiration from a number of African and African diaspora intellectuals including Cheikh Anta Diop, George James, Harold Cruse, Ida B. Wells, Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, and W. E. B. Du Bois. The Temple Circle, also known as the Temple School of Thought, Temple Circle of Afrocentricity, or Temple School of Afrocentricity, was an early group of Africologists during the late 1980s and early 1990s that helped to further develop Afrocentricity, which is based on concepts of agency, centeredness, location, and orientation.

Black feminism, also known as Afro-feminism chiefly outside the United States, is a branch of feminism that centers around black women.

African feminism includes theories and movements which specifically address the experiences and needs of continental African women. From a western perspective, these theories and movements fall under the umbrella label of Feminism, but it is important to note that many branches of African "feminism" actually resist this categorization. African women have been engaged in gender struggle since long before the existence of the western-inspired label "African feminism," and this history is often neglected. Despite this caveat, this page will use the term feminism with regard to African theories and movements in order to fit into a relevant network of existing Wikipedia pages on global feminism. Because Africa is not a monolith, no single feminist theory or movement reflects the entire range of experiences African women have. African feminist theories are sometimes aligned, in dialogue, or in conflict with Black Feminism or African womanism. This page covers general principles of African feminism, several distinct theories, and a few examples of feminist movements and theories in various African countries.

"Africana womanism" is a term coined in the late 1980s by Clenora Hudson-Weems, intended as an ideology applicable to all women of African descent. It is grounded in African culture and Afrocentrism and focuses on the experiences, struggles, needs, and desires of Africana women of the African diaspora. It distinguishes itself from feminism, or Alice Walker's womanism. Africana womanism pays more attention to and focuses more on the realities and the injustices in society in regard to race.

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

Feminist political theory is an area of philosophy that focuses on understanding and critiquing the way political philosophy is usually construed and on articulating how political theory might be reconstructed in a way that advances feminist concerns. Feminist political theory combines aspects of both feminist theory and political theory in order to take a feminist approach to traditional questions within political philosophy.

Hip hop feminism is a sub-set of black feminism that centers on intersectional subject positions involving race and gender in a way that acknowledges the contradictions in being a black feminist, such as black women's enjoyment in hip hop music and culture, rather than simply focusing on the victimization of black women in hip hop culture due to interlocking systems of oppressions involving race, class, and gender.

In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of depicting women and the world in the visual arts and in literature from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. In the visual and aesthetic presentations of narrative cinema, the male gaze has three perspectives: (i) that of the man behind the camera, (ii) that of the male characters within the film's cinematic representations; and (iii) that of the spectator gazing at the image.

Feminist activism in hip hop is a feminist movement based by hip hop artists. The activism movement involves doing work in graffiti, break dancing, and hip hop music. Hip hop has a history of being a genre that sexually objectifies and disrespects women ranging from the usage of video vixens to explicit rap lyrics. Within the subcultures of graffiti and breakdancing, sexism is more evident through the lack of representation of women participants. In a genre notorious for its sexualization of women, feminist groups and individual artists who identify as feminists have sought to change the perception and commodification of women in hip hop. This is also rooted in cultural implications of misogyny in rap music.

Sarojini Nadar is a South African theologian and biblical scholar who is the Desmond Tutu Research Chair in Religion and Social Justice at the University of the Western Cape.