Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. In about 0.5 percent of cases, it moves from the gut to affect the central nervous system, and there is muscle weakness resulting in a flaccid paralysis. This can occur over a few hours to a few days. The weakness most often involves the legs, but may less commonly involve the muscles of the head, neck, and diaphragm. Many people fully recover. In those with muscle weakness, about 2 to 5 percent of children and 15 to 30 percent of adults die. Up to 70 percent of those infected have no symptoms. Another 25 percent of people have minor symptoms such as fever and a sore throat, and up to 5 percent have headache, neck stiffness, and pains in the arms and legs. These people are usually back to normal within one or two weeks. Years after recovery, post-polio syndrome may occur, with a slow development of muscle weakness similar to that which the person had during the initial infection.

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all children be fully vaccinated against polio. The two vaccines have eliminated polio from most of the world, and reduced the number of cases reported each year from an estimated 350,000 in 1988 to 33 in 2018.

John Franklin Enders was an American biomedical scientist and Nobel Laureate. Enders has been called "The Father of Modern Vaccines."

March of Dimes is a United States nonprofit organization that works to improve the health of mothers and babies. The organization was founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938, as the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, to combat polio. The name "March of Dimes" was coined by Eddie Cantor. After funding Jonas Salk's polio vaccine, the organization expanded its focus to the prevention of birth defects and infant mortality. In 2005, as preterm birth emerged as the leading cause of death for children worldwide, research and prevention of premature birth became the organization's primary focus.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) AIDS hypothesis is a now-discredited hypothesis that the AIDS pandemic originated from live polio vaccines prepared in chimpanzee tissue cultures, accidentally contaminated with simian immunodeficiency virus and then administered to up to one million Africans between 1957 and 1960 in experimental mass vaccination campaigns.

Albert Bruce Sabin was a Polish-American medical researcher, best known for developing the oral polio vaccine, which has played a key role in nearly eradicating the disease. In 1969–72, he served as the President of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Hilary Koprowski was a Polish virologist and immunologist active in the United States who demonstrated the world's first effective live polio vaccine. He authored or co-authored over 875 scientific papers and co-edited several scientific journals.

Thomas Milton Rivers was an American bacteriologist and virologist. He has been described as the "father of modern virology."

Polio: An American Story by David M. Oshinsky, professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, documents the polio epidemic in the United States during the 1940s and 1950s and the race to develop a vaccine, which led to 2 different types of polio vaccine: inactivated poliovirus vaccine, developed by a team led by Jonas Salk, and oral poliovirus vaccine, developed by a team led by Albert Sabin. Published in 2005 by the Oxford University Press, it won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for History and the 2005 Herbert Hoover Book Award.

The history of polio (poliomyelitis) infections began during prehistory. Although major polio epidemics were unknown before the 20th century, the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Over millennia, polio survived quietly as an endemic pathogen until the 1900s when major epidemics began to occur in Europe. Soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the United States. By 1910, frequent epidemics became regular events throughout the developed world primarily in cities during the summer months. At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyze or kill over half a million people worldwide every year.

Isabel Merrick Morgan was an American virologist at Johns Hopkins University, who prepared an experimental vaccine that protected monkeys against polio in a research team with David Bodian and Howard A. Howe. Their research led to the identification of three distinct serotypes of poliovirus, all of which must be incorporated for a vaccine to provide complete immunity from poliomyelitis. Morgan was the first to successfully use a killed-virus for polio inoculation in monkeys. After she married in 1949, she left the field of polio research in part because she was uncomfortable with trials that tested polio vaccines on the nerve tissue of children. She then worked on epidemiological studies on air pollution. Later in life, she was a consultant for studies of cancer therapies at the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute.

Mikhail Petrovich Chumakov was a Soviet microbiologist and virologist most famous for conducting pivotal large-scale clinical trials that led to licensing of the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) developed by Albert B. Sabin.

Jonas Edward Salk was an American virologist and medical researcher who developed one of the first successful polio vaccines. He was born in New York City and attended the City College of New York and New York University School of Medicine.

Joseph Louis Melnick was an American epidemiologist who performed breakthrough research on the spread of polio. The New York Times called him "a founder of modern virology".

Preben Christian Alexander von Magnus was a Danish virologist who is known for his research on influenza, polio vaccination and monkeypox. He gave his name to the Von Magnus phenomenon.

Julius S. Youngner was an American Distinguished Service Professor in the School of Medicine and Department of Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at University of Pittsburgh responsible for advances necessary for development of a vaccine for poliomyelitis and the first intranasal equine influenza vaccine.

Harry M. Weaver was an American neuroscientist and researcher who made contributions to medical research in the fields of Multiple sclerosis, and was the Director of Research at the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis when the Polio vaccine was discovered and developed by Jonas Salk. Dr. Weaver also served as the Vice President for Research at the American Cancer Society, Vice President for Research and Development at the Schering Corporation, and as the Director of Research at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Herdis von Magnus was a Danish virologist and polio expert. After working with Jonas Salk, she and her husband directed the first polio vaccination program in Denmark. She also researched encephalitis.

Marina Konstantinovna Voroshilova was a Soviet virologist and corresponding member of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR (1969). She is best known for her work on the introduction of vaccines against poliomyelitis, the discovery of non-specific effects of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), and developing the concept of beneficial human viruses.

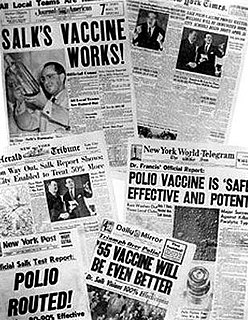

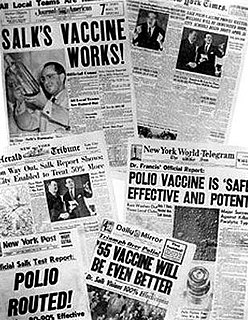

The announcement of the polio vaccine's safety and effectiveness was on April 12, 1955, by Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., of the University of Michigan, the monitor of the test results. Within minutes of his announcement to the audience of scientists and reporters, news of the event was carried coast to coast by wire services and radio and television newscasts. When the vaccine was announced as successful, therefore, it led to spontaneous celebrations across the United States. It was the world's first successful polio vaccine, declared “safe, effective, and potent.” It was possibly the most significant biomedical advance of the past century.