Related Research Articles

Cnidaria is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

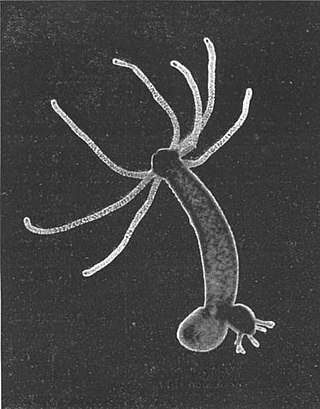

Hydra is a genus of small freshwater organisms of the phylum Cnidaria and class Hydrozoa. They are native to the temperate and tropical regions. The genus was named by Linnaeus in 1758 after the Hydra, which was the many-headed beast defeated by Heracles, as when the animal had a part severed, it would regenerate much like the hydra’s heads. Biologists are especially interested in Hydra because of their regenerative ability; they do not appear to die of old age, or to age at all.

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column, derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate subphylum Vertebrata. Familiar examples of invertebrates include arthropods, mollusks, annelids, echinoderms and cnidarians.

Placozoa is a phylum of the simple animals that are marine and free-living (non-parasitic). Placozoans are simply blob-like animals without any body part or organ, and are merely aggregates of cells. Moving in water by ciliary motion, eating food by engulfment, reproducing by fission or budding, they are described as "the simplest animals on Earth." Structural and molecular analyses have supported them as among the most basal animals, thus, constituting the most primitive metazoan phylum.

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera, are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through them, consisting of jelly-like mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of cells.

A cnidocyte is an explosive cell containing one large secretory organelle called a cnidocyst that can deliver a sting to other organisms. The presence of this cell defines the phylum Cnidaria. Cnidae are used to capture prey and as a defense against predators. A cnidocyte fires a structure that contains a toxin within the cnidocyst; this is responsible for the stings delivered by a cnidarian.

Ctenophora comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming, and they are the largest animals to swim with the help of cilia.

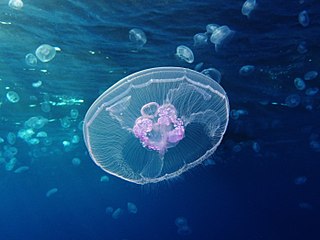

Aurelia aurita is a species of the genus Aurelia. All species in the genus are very similar, and it is difficult to identify Aurelia medusae without genetic sampling; most of what follows applies equally to all species of the genus.

A nerve net consists of interconnected neurons lacking a brain or any form of cephalization. While organisms with bilateral body symmetry are normally associated with a condensation of neurons or, in more advanced forms, a central nervous system, organisms with radial symmetry are associated with nerve nets, and are found in members of the Ctenophora, Cnidaria, and Echinodermata phyla, all of which are found in marine environments. In the Xenacoelomorpha, a phylum of bilaterally symmetrical animals, members of the subphylum Xenoturbellida also possess a nerve net. Nerve nets can provide animals with the ability to sense objects through the use of the sensory neurons within the nerve net.

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work mainly like muscular hydrostats. Most forms of tentacles are used for grasping and feeding. Many are sensory organs, variously receptive to touch, vision, or to the smell or taste of particular foods or threats. Examples of such tentacles are the eyestalks of various kinds of snails. Some kinds of tentacles have both sensory and manipulatory functions.

Ascidiacea, commonly known as the ascidians or sea squirts, is a paraphyletic class in the subphylum Tunicata of sac-like marine invertebrate filter feeders. Ascidians are characterized by a tough outer "tunic" made of a polysaccharide.

Coelenterata is a term encompassing the animal phyla Cnidaria and Ctenophora. The name comes from Ancient Greek κοῖλος (koîlos) 'hollow', and ἔντερον (énteron) 'intestine', referring to the hollow body cavity common to these two phyla. They have very simple tissue organization, with only two layers of cells, and radial symmetry. Some examples are corals, which are typically colonial, and hydrae, jellyfish, and sea anemones, which are solitary. Coelenterata lack a specialized circulatory system relying instead on diffusion across the tissue layers.

Colloblasts are unique, multicellular structures found in ctenophores. They are widespread in the tentacles of these animals and are used to capture prey. Colloblasts consist of a collocyte containing a coiled spiral filament, internal granules and other organelles.

Mesoglea refers to the extracellular matrix found in cnidarians like coral or jellyfish that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. It is related to but distinct from mesohyl, which generally refers to extracellular material found in sponges.

Mesenchyme is a type of loosely organized animal embryonic connective tissue of undifferentiated cells that give rise to most tissues, such as skin, blood or bone. The interactions between mesenchyme and epithelium help to form nearly every organ in the developing embryo.

Bioadhesives are natural polymeric materials that act as adhesives. The term is sometimes used more loosely to describe a glue formed synthetically from biological monomers such as sugars, or to mean a synthetic material designed to adhere to biological tissue.

Cydippida is an order of comb jellies. They are distinguished from other comb jellies by their spherical or oval bodies, and the fact their tentacles are branched, and can be retracted into pouches on either side of the pharynx. The order is not monophyletic, that is, more than one common ancestor is believed to exist.

Snail slime (mucopolysaccharide) is a kind of mucus produced by snails, which are gastropod mollusks. Land snails and slugs both produce mucus, as does every other kind of gastropod, from marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats. The reproductive system of gastropods also produces mucus internally from special glands.

Arthropods, including insects and spiders, make use of smooth adhesive pads as well as hairy pads for climbing and locomotion along non-horizontal surfaces. Both types of pads in insects make use of liquid secretions and are considered 'wet'. Dry adhesive mechanisms primarily rely on Van der Waals' forces and are also used by organisms other than insects. The fluid provides capillary and viscous adhesion and appears to be present in all insect adhesive pads. Little is known about the chemical properties of the adhesive fluids and the ultrastructure of the fluid-producing cells is currently not extensively studied. Additionally, both hairy and smooth types of adhesion have evolved separately numerous times in insects. Few comparative studies between the two types of adhesion mechanisms have been done and there is a lack of information regarding the forces that can be supported by these systems in insects. Additionally, tree frogs and some mammals such as the arboreal possum and bats also make use of smooth adhesive pads. The use of adhesive pads for locomotion across non-horizontal surfaces is a trait that evolved separately in different species, making it an example of convergent evolution. The power of adhesion allows these organisms to be able to climb on almost any substance.

Rhabditophora is a class of flatworms. It includes all parasitic flatworms and most free-living species that were previously grouped in the now obsolete class Turbellaria. Therefore, it contains the majority of the species in the phylum Platyhelminthes, excluding only the catenulids, to which they appear to be the sister group.

References

- 1 2 Buvat, Roger (1989). Ontogeny, cell differentiation, and structure of vascular plants. Berlin New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387192130.

- ↑ Cloney, Richard A.; Larval adhesive organs and metamorphosis in ascidians; Cell and Tissue Research, Volume 183, Number 4, 423-444, DOI: 10.1007/BF00225658; 1977

- ↑ Cloney, Richard A.; Larval adhesive organs and metamorphosis in ascidians II. The mechanism of eversion of the papillae of Distaplia occidentalis; Cell and Tissue Research, Volume 200, Number 3, 453-473, DOI: 10.1007/BF00234856; 1979

- ↑ Eeckhaut, I. et al. Functional morphology of the tentacles and tentilla of Coeloplana bannworthi (Ctenophora, Platyctenida), an ectosymbiont of Diadema setosum (Echinodermata, Echinoida); Zoomorphology Volume 117, Number 3, 165-174, DOI: 10.1007/s004350050041; 1997

- 1 2 Harmer, Sir Sidney Frederic; Shipley, Arthur Everett et alia: The Cambridge natural history Volume 1, Protozoa, Porifera, Coelenterata, Ctenophora, Echinodermata. Macmillan Company 1906

- ↑ J. Edward Bruni; Donald G. Montemurro (2009). Human Neuroanatomy: A Text, Brain Atlas, and Laboratory Dissection Guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-19-537142-0.

- ↑ Simpson, Tracy (1984). The cell biology of sponges. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387908939.

- 1 2 von Byern, Janek; Grunwald, Ingo (2010). Biological adhesive systems : from nature to technical and medical application. Wien u.a: Springer. ISBN 9783709101414.

- ↑ Whittington ID, Cribb BW. Adhesive secretions in the Platyhelminthes. Adv Parasitol. 2001;48:101-224

- 1 2 Lengerer B, Pjeta R, Wunderer J, Rodrigues M, Arbore R, Schärer L, Berezikov E, Hess MW, Pfaller K, Egger B, Obwegeser S, Salvenmoser W, Ladurner P. Biological adhesion of the flatworm Macrostomum lignano relies on a duo-gland system and is mediated by a cell type-specific intermediate filament protein. Front Zool. 2014 Feb 12;11(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-11-12.

- ↑ Martin, Gary G. The duo-gland adhesive system of the archiannelids Protodrilus and Saccocirrus and the turbellarian Monocelis. Zoomorphology 01/1978; 91(1):63-75. DOI:10.1007/BF00994154

- ↑ Jangoux, Michel. Echinoderm studies 5 (1996) Publisher: CRC Press 1996. ISBN 978-9054106395

- ↑ CHENG, THOMAS C.; YEE, HERBERT W. F.; RIFKIN, ERIK. Studies on the Internal Defense Mechanisms of Sponges. PACIFIC SCIENCE, Vol. XXII, July 1968

- ↑ Lankester, E. Ray. A treatise on zoology. Volume 2. London, A. and C. Black 1900

- ↑ LI Hui, ZHANG Xiao-Yun, WANG An-Tai. Exploration on primordial nervous substances in sponges. Current Zoology(formerly Acta Zoologica Sinica), Dec. 2005, 51(6):1091 - 1101