The National Labor Union (NLU) is the first national labor federation in the United States. Founded in 1866 and dissolved in 1873, it paved the way for other organizations, such as the Knights of Labor and the AFL. It was led by William H. Sylvis and Andrew Cameron.

The American Negro Labor Congress was established in 1925 by the Communist Party as a vehicle for advancing the rights of African Americans, propagandizing for communism within the black community and recruiting African American members for the party.

The Bureau of Colored Troops was created by the United States War Department on May 22, 1863, under General Order No. 143, during the Civil War, to handle "all matters relating to the organization of colored troops." Major Charles W. Foster was chief of the Bureau, which reported to Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. The designation United States Colored Troops replaced the varied state titles that had been given to the African-American soldiers.

The Communist Party USA, ideologically committed to foster a socialist revolution in the United States, played a significant role in defending the civil rights of African Americans during its most influential years of the 1930s and 1940s. In that period, the African-American population was still concentrated in the South, where it was largely disenfranchised, excluded from the political system, and oppressed under Jim Crow laws.

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

The Militia Act of 1862 was an Act of the 37th United States Congress, during the American Civil War, that authorized a militia draft within a state when the state could not meet its quota with volunteers. The Act, for the first time, also allowed African-Americans to serve in the militias as soldiers and war laborers. Previous to it, since the Militia Acts of 1792, only white male citizens were permitted to participate in the militias.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress was an American organization established in 1937 at a conference in Richmond, Virginia. It was established as a left-wing civil rights organization, arising from the National Negro Congress (NNC) and the leftist student movement of the 1930s. The SNYC aimed to empower black people in the Southern region to fight for their rights and envisioned interracial working-class coalitions as the way to dismantle the southern caste system. The NNC itself had been created in 1936 to address the economic and discriminatory challenges faced by African Americans, especially in New Deal programs.

Labor federation competition in the United States is a history of the labor movement, considering U.S. labor organizations and federations that have been regional, national, or international in scope, and that have united organizations of disparate groups of workers. Union philosophy and ideology changed from one period to another, conflicting at times. Government actions have controlled, or legislated against particular industrial actions or labor entities, resulting in the diminishing of one labor federation entity or the advance of another.

The National Negro Labor Council (1950–1955) was an advocacy group dedicated to serving the needs and civil rights of black workers. Many union leaders of the CIO and AFL considered it a Communist front. In 1951 it was officially branded a communist front organization by U.S. attorney general Herbert Brownwell.

Benjamin DeWayne Amis, known as B. D. Amis, was an African-American labor organizer and civil rights leader. Particularly influential in the fight for African Americans and workers during the period of official segregation in the South and informal discrimination throughout the country, Amis is most remembered for his militant Communist activism on behalf of the notable legal cases of the falsely-accused Scottsboro Boys, the African-American organizer Angelo Herndon, as well as the white labor leader Tom Mooney.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the Black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

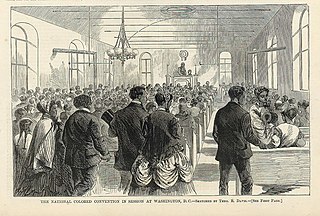

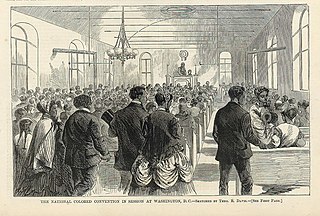

The Colored Conventions Movement, or Black Conventions Movement, was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War. The delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and formerly enslaved African Americans, including religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, editors, and abolitionists. The conventions provided "an organizational structure through which black men could maintain a distinct black leadership and pursue black abolitionist goals." Colored conventions occurred in thirty-one states across the United States and in Ontario, Canada. The movement involved more than five thousand delegates and tens of thousands of attendees.

Isaac Myers was a pioneering African American trade unionist, a co-operative organizer and a caulker from Baltimore, Maryland.

The Negro Sanhedrin was a national "All-Race Conference" held in the American city of Chicago, Illinois, from February 11 to 15, 1924. The gathering was attended by 250 delegates representing 61 trade unions, civic groups, and fraternal organizations in a short-lived attempt to forge a national program protecting the legal rights of African-American tenant farmers and wage workers and extending the scope of civil rights.

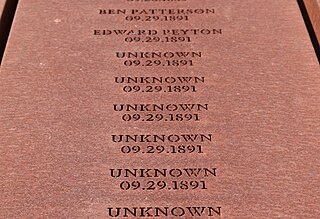

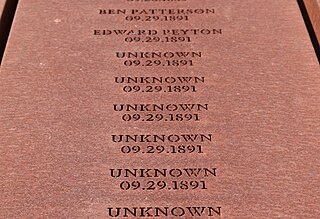

The cotton pickers' strike of 1891 was a labor action of African-American sharecroppers in Lee County, Arkansas in September, 1891. The strike led to open conflict between strikers and plantation owners, racially-motivated violence, and both a sheriff's posse and a lynching party. One plantation manager, two non-striking workers, and some twelve strikers were killed during the incident. Nine of those strikers were hung in a mass lynching on the evening of September 29.

Helen Appo Cook was a wealthy, prominent African-American community activist in Washington, D.C., and a leader in the women's club movement. Cook was a founder and president of the Colored Women's League, which consolidated with another organization in 1896 to become the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), an organization still active in the 21st century. Cook supported voting rights and was a member of the Niagara Movement, which opposed racial segregation and African American disenfranchisement. In 1898, Cook publicly rebuked Susan B. Anthony, president of the National Woman's Suffrage Association, and requested she support universal suffrage following Anthony's speech at a U.S. Congress House Committee on Judiciary hearing.

James H. Alston was an American state legislator in Alabama. He served in the legislature in 1868 and from 1869 to 1879.

Henry O. Mayfield was an American miner and social activist. Mayfield was one of the Black miners who played an active role in forming the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) between 1935 and 1955; he also had a leadership role in the SNYC. He served the United States as a soldier in World War II; afterwards, he and other veterans worked to support voting rights. He worked with other Black leaders in the Congress of Industrial Organizations to advocate for the rights of laborers, especially in the southern United States. Mayfield was watched by the FBI and was arrested for his work in the Communist Party and advocacy for civil rights. Mayfield served as chairman of the board for Freedomways Associates, the publishing company for the cultural magazine Freedomways, up until his death.

The American League of Colored Laborers was a short-lived labor union established in New York City in 1850. It is notable for being the first union created for African Americans in the United States. Social reformer Frederick Douglass assisted in organizing the group, which held its first meeting at the Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on June 13, 1850. Its initial officers included Samuel Ringgold Ward as president, Douglass and Lewis Woodson as vice presidents, and Henry Bibb as secretary, and during the first meeting, an executive committee was organized that was composed of several notable social reformers and abolitionists. In addition to union activities, the league was also envisioned to serve as a benefit society for black tradespeople and entrepreneurs, and to this effect, its leaders planned to establish a mutual savings bank and hold an industrial fair. Despite these plans, the union faltered shortly after its creation, and it would take until 1869 that the first successful national labor union for African Americans, the Colored National Labor Union, was formed.