The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the national frame and constraints of government. The Constitution's first three articles embody the doctrine of the separation of powers, whereby the federal government is divided into three branches: the legislative, consisting of the bicameral Congress ; the executive, consisting of the president and subordinate officers ; and the judicial, consisting of the Supreme Court and other federal courts. Article IV, Article V, and Article VI embody concepts of federalism, describing the rights and responsibilities of state governments, the states in relationship to the federal government, and the shared process of constitutional amendment. Article VII establishes the procedure subsequently used by the 13 states to ratify it. The Constitution of the United States is the oldest and longest-standing written and codified national constitution in force in the world.

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Three empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising under federal law, as well as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the right to keep and bear arms. It was ratified on December 15, 1791, along with nine other articles of the Bill of Rights. In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the Supreme Court affirmed for the first time that the right belongs to individuals, for self-defense in the home, while also including, as dicta, that the right is not unlimited and does not preclude the existence of certain long-standing prohibitions such as those forbidding "the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill" or restrictions on "the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons". In McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010) the Supreme Court ruled that state and local governments are limited to the same extent as the federal government from infringing upon this right. New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022) assured the right to carry weapons in public spaces with reasonable exceptions.

The Commentaries on the Laws of England are an influential 18th-century treatise on the common law of England by Sir William Blackstone, originally published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford between 1765 and 1769. The work is divided into four volumes, on the rights of persons, the rights of things, of private wrongs and of public wrongs.

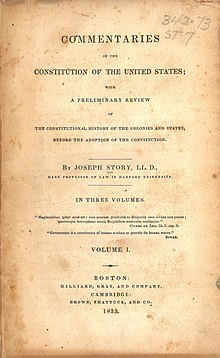

Joseph Story was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee and United States v. The Amistad, and especially for his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, first published in 1833. Dominating the field in the 19th century, this work is a cornerstone of early American jurisprudence. It is the second comprehensive treatise on the provisions of the U.S. Constitution and remains a critical source of historical information about the forming of the American republic and the early struggles to define its law.

The Titles of Nobility Amendment is a proposed and still-pending amendment to the United States Constitution. The 11th Congress passed it on May 1, 1810, and submitted to the state legislatures for ratification. It would strip United States citizenship from any citizen who accepted a title of nobility from an "emperor, king, prince or foreign power". On two occasions between 1812 and 1816, it was within two states of the number needed to become part of the Constitution. Congress did not set a time limit for its ratification, so the amendment is still pending before the states.

The Three-fifths Compromise was an agreement reached during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention over the inclusion of slaves in a state's total population. This count would determine: the number of seats in the House of Representatives; the number of electoral votes each state would be allocated; and how much money the states would pay in taxes. Slave holding states wanted their entire population to be counted to determine the number of Representatives those states could elect and send to Congress. Free states wanted to exclude the counting of slave populations in slave states, since those slaves had no voting rights. A compromise was struck to resolve this impasse. The compromise counted three-fifths of each state's slave population toward that state's total population for the purpose of apportioning the House of Representatives, effectively giving the Southern states more power in the House relative to the Northern states. It also gave slaveholders similarly enlarged powers in Southern legislatures; this was an issue in the secession of West Virginia from Virginia in 1863. Free blacks and indentured servants were not subject to the compromise, and each was counted as one full person for representation.

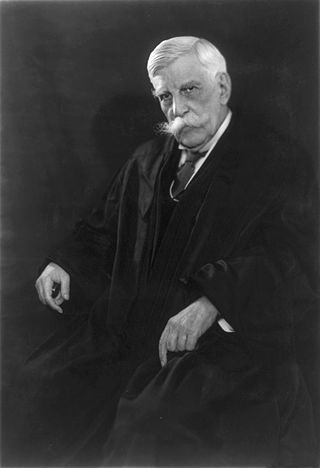

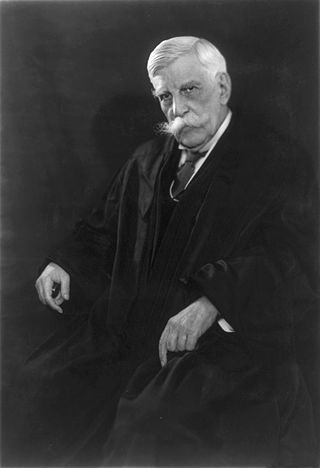

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1902 to 1932. Holmes is one of the most widely cited Supreme Court justices and among the most influential American judges in history, noted for his long service, pithy opinions—particularly those on civil liberties and American constitutional democracy—and deference to the decisions of elected legislatures. Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90, an unbeaten record for oldest justice on the Supreme Court. He previously served as a Brevet Colonel in the American Civil War, in which he was wounded three times, as an associate justice and chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and as Weld Professor of Law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School. His positions, distinctive personality, and writing style made him a popular figure, especially with American progressives.

Henry Baldwin was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from January 6, 1830, to April 21, 1844.

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." It mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law.

Nathan Dane was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the Continental Congress from 1785 through 1788. Dane helped formulate the Northwest Ordinance while in Congress, and introduced an amendment to the ordinance prohibiting slavery in the Northwest Territory.

In United States constitutional law, incorporation is the doctrine by which portions of the Bill of Rights have been made applicable to the states. When the Bill of Rights was ratified, the courts held that its protections extended only to the actions of the federal government and that the Bill of Rights did not place limitations on the authority of the state and local governments. However, the post–Civil War era, beginning in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment, which declared the abolition of slavery, gave rise to the incorporation of other amendments, applying more rights to the states and people over time. Gradually, various portions of the Bill of Rights have been held to be applicable to state and local governments by incorporation via the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868.

Christian amendment describes any of several attempts to amend a country's constitution in order to officially make it a Christian state.

The Privileges and Immunities Clause prevents a state from treating citizens of other states in a discriminatory manner. Additionally, a right of interstate travel is associated with the clause.

The Taxing and Spending Clause, Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution, grants the federal government of the United States its power of taxation. While authorizing Congress to levy taxes, this clause permits the levying of taxes for two purposes only: to pay the debts of the United States, and to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States. Taken together, these purposes have traditionally been held to imply and to constitute the federal government's taxing and spending power.

Thomas McIntyre Cooley was the 25th Justice and a Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, between 1864 and 1885. Born in Attica, New York, he was father to Charles Cooley, a distinguished American sociologist. He was a charter member and first chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission (1887).

The Marshall Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1801 to 1835, when John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Roger Taney took office. The Marshall Court played a major role in increasing the power of the judicial branch, as well as the power of the national government.

John Marshall was an American statesman, lawyer, and Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longest serving justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, and is widely regarded as one of the most influential justices ever to serve. Prior to joining the court, Marshall briefly served as both the U.S. secretary of state under President John Adams, and a representative, in the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia, thereby making him one of the few Americans to serve on all three branches of the United States federal government.

A general welfare clause is a section that appears in many constitutions and in some charters and statutes that allows that the governing body empowered by the document to enact laws to promote the general welfare of the people, which is sometimes worded as the public welfare. In some countries, it has been used as a basis for legislation promoting the health, safety, morals, and well-being of the people governed by it.

An unconstitutional constitutional amendment is a concept in judicial review based on the idea that even a properly passed and properly ratified constitutional amendment, specifically one that is not explicitly prohibited by a constitution's text, can nevertheless be unconstitutional on substantive grounds—such as due to this amendment conflicting with some constitutional or even extra-constitutional norm, value, and/or principle. As Israeli legal academic Yaniv Roznai's 2017 book Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: The Limits of Amendment Powers demonstrates, the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine has been adopted by various courts and legal scholars in various countries throughout history. While this doctrine has generally applied specifically to constitutional amendments, there have been moves and proposals to also apply this doctrine to original parts of a constitution.