Related Research Articles

The 1936 United States presidential election was the 38th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1936. In the midst of the Great Depression, incumbent Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Republican Governor Alf Landon of Kansas. Roosevelt won the highest share of the popular vote and the electoral vote (98.49%) since the largely uncontested 1820 election. The sweeping victory consolidated the New Deal Coalition in control of the Fifth Party System.

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making the purpose of the convention to select a new presidential nominee for the Democratic Party. The keynote speaker was Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii. Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine were nominated for president and vice president, respectively. The most contentious issues of the convention were the continuing American military involvement in the Vietnam War and voting reform, particularly expanding the right to vote for draft-age soldiers who were unable to vote as the voting age was 21. The convention also marked a turning point where previously idle groups such as youth and minorities became more involved in politics and voting.

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was an American politician and diplomat who was the United States Ambassador to the United Nations from 1961 until his death in 1965. He previously served as the 31st governor of Illinois from 1949 to 1953 and was the Democratic nominee for president of the United States in 1952 and 1956, losing both elections to Dwight D. Eisenhower in a landslide. Stevenson was the grandson of Adlai Stevenson I, the 23rd vice president of the United States.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served as vice president from 1961 to 1963. A Democrat from Texas, Johnson also served as a U.S. representative and senator.

David Dean Rusk was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the Franklin Roosevelt administration. He had been a high government official in the 1940s and early 1950s, as well as the head of a leading foundation. He is cited as one of the two officers responsible for dividing the two Koreas at the 38th parallel.

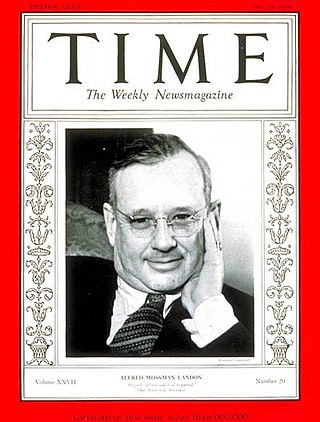

Alfred Mossman Landon was an American oilman and politician who served as the 26th governor of Kansas from 1933 to 1937. A member of the Republican Party, he was the party's nominee in the 1936 presidential election, and was defeated in a landslide by incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. was an American diplomat and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate and served as United States Ambassador to the United Nations in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1960, he was the Republican nominee for Vice President on a ticket with Richard Nixon, who had served two terms as Eisenhower's vice president. The Republican ticket narrowly lost to Democrats John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson; Lodge later served as a diplomat in the administrations of Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Gerald Ford and was a presidential contender in 1964.

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California, on July 11–15, 1960. It nominated Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts for president and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas for vice president.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, often referred to by his initials JFK and by the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the youngest person to assume the presidency by election and the youngest president at the end of his tenure. Kennedy served at the height of the Cold War, and the majority of his foreign policy concerned relations with the Soviet Union and Cuba. A Democrat, Kennedy represented Massachusetts in both houses of the U.S. Congress prior to his presidency.

The Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign began on March 16, 1968, when Robert Francis Kennedy, a United States Senator from New York, mounted an unlikely challenge to incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson. Following an upset in the New Hampshire primary, Johnson announced on March 31 that he would not seek re-election. Kennedy still faced two rival candidates for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination: the leading challenger United States Senator Eugene McCarthy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey had entered the race after Johnson's withdrawal, but Kennedy and McCarthy remained the main challengers to the policies of the Johnson administration. During the spring of 1968, Kennedy led a leading campaign in presidential primary elections throughout the United States. Kennedy's campaign was especially active in Indiana, Nebraska, Oregon, South Dakota, California, and Washington, D.C. Kennedy's campaign ended on June 6, 1968 when he died following his assassination after declaring victory in the June 4, 1968 California Primary. He was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, following his victory speech in the California primary and died on June 6, 1968 at Good Samaratin Hospital in Los Angeles. Had Kennedy been elected President in November of 1968, he would have been the first brother of a U.S. President to win the presidency himself.

On April 4, 1968, United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York delivered an improvised speech several hours after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Kennedy, who was campaigning to earn the Democratic Party's presidential nomination, made his remarks while in Indianapolis, Indiana, after speaking at two Indiana universities earlier in the day. Before boarding a plane to attend campaign rallies in Indianapolis, he learned that King had been shot in Memphis, Tennessee. Upon arrival, Kennedy was informed that King had died. His own brother, John Fitzgerald Kennedy had been assassinated on November 22, 1963. Robert F. Kennedy would be also assassinated two months after this speech, while campaigning for presidential nomination at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California.

Robert F. Kennedy's Day of Affirmation Address is a speech given to National Union of South African Students members at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, on June 6, 1966, on the University's "Day of Reaffirmation of Academic and Human Freedom". Kennedy was at the time the junior U.S. senator from New York. His overall trip brought much attention to Africa as a whole.

From March to July 1968, Democratic Party voters elected delegates to the 1968 Democratic National Convention for the purpose of selecting the party's nominee for President in the upcoming election. After an inconclusive and tumultuous campaign marred by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey was nominated at the 1968 Democratic National Convention held from August 26 to August 29, 1968, in Chicago, Illinois.

Robert Francis Kennedy, also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New York from January 1965 until his assassination in June 1968, when he was running for the Democratic presidential nomination. Like his brothers John F. Kennedy and Ted Kennedy, he was a prominent member of the Democratic Party and is an icon of modern American liberalism.

The inauguration of John F. Kennedy as the 35th president of the United States was held on Friday, January 20, 1961, at the East Portico of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. It was the 44th inauguration, marking the commencement of John F. Kennedy's and Lyndon B. Johnson's only term as president and vice president. Kennedy was assassinated 2 years, 306 days into this term, and Johnson succeeded to the presidency.

"On the Mindless Menace of Violence" is a speech given by United States Senator and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy. He delivered it in front of the City Club of Cleveland at the Sheraton-Cleveland Hotel on April 5, 1968, the day after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. With the speech, Kennedy sought to counter the King-related riots and disorder emerging in various cities, and address what he viewed as the growing problem of violence in American society.

Robert F. Kennedy's speech at Ball State University was given on April 4, 1968, in Muncie, Indiana.

The Alfred M. Landon Lecture Series is a series of speeches on current public affairs, which is organized and hosted by Kansas State University, in Manhattan, Kansas, United States. It is named after Kansas politician Alf Landon, former Governor of Kansas and Republican presidential candidate. The first lecture in the series was given by Landon on December 13, 1966.

Robert F. Kennedy's remarks at the University of Kansas were given on March 18, 1968. He spoke about student protests, the Vietnam War, and the gross national product. At the time, Kennedy's words on the latter subject went relatively unnoticed, but they have since become famous.

Let Us Continue was a speech that 36th President of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson delivered to a joint session of Congress on November 27, 1963, five days after the assassination of his predecessor John F. Kennedy. The almost 25-minute speech is considered one of the most important in his political career.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Newfield, Jack (1988). Robert Kennedy: A Memoir (reprint ed.). New York: Penguin Group. pp. 232–234. ISBN 0-452-26064-7.

- ↑ Thomas, Evan (2013). Robert Kennedy: His Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 363. ISBN 9781476734569.

- ↑ Savage, Sean J. (2004). JFK, LBJ, and the Democratic Party. SUNY series in the presidency (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 293. ISBN 9780791461693.

- ↑ Shesol, Jeff (1998). Mutual Contempt: Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy and the Feud That Defined a Decade (illustrated ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 424. ISBN 9780393318555.

- ↑ Palermo, Joseph A. (2002). In His Own Right: The Political Odyssey of Senator Robert F. Kennedy (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 191. ISBN 9780231120692.

- ↑ "Landon Lecture Series on Public Issues — Series Speakers". Kansas State University . Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ↑ Larry, Tye (May 9, 2017). Bobby Kennedy : the making of a liberal icon. New York. ISBN 9780812983500. OCLC 935987185.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)