Related Research Articles

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many veto points. In order to bypass constitutional obstacles and force through the political goals of the three men, they forged in secret an alliance where they promised to use their respective influence to support each other. The "triumvirate" was not a formal magistracy, nor did it achieve a lasting domination over state affairs.

In ancient Rome, the plebeians were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

Optimates and populares are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated academic discussion" as to whether Romans would have recognised an ideological content or political split in the label.

Lucius Cornelius Sisenna was a Roman soldier, historian, and annalist. He was praetor in 78 BC.

The Curiate Assembly was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome were organized into thirty units called "Curiae". The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original patrician (aristocratic) clans. The Curiae formed an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls, and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly. While plebeians (commoners) could participate in this assembly, only the patricians could vote.

Publius Vatinius was a Roman politician during the last decades of the Republic. He served as a Caesarian-allied plebeian tribune in the year 59 – he was the tribune that proposed the law giving Caesar his Gallic command – and later fought on that side of the civil war. Caesar made him consul in 47 BC; he later fought in Illyricum for the Caesarians and celebrated a triumph for his victories there in 42 BC.

The term accensi is applied to two different groups. Originally, the accensi were light infantry in the armies of the early Roman Republic. They were the poorest men in the legion, and could not afford much equipment. They did not wear armour or carry shields, and their usual position was part of the third battle line. They fought in a loose formation, supporting the heavier troops. They were eventually phased out by the time of Second Punic War. In the later Roman Republic the term was used for civil servants who assisted the elected magistrates, particularly in the courts, where they acted as ushers and clerks.

The Comitium was the original open-air public meeting space of Ancient Rome, and had major religious and prophetic significance. The name comes from the Latin word for "assembly". The Comitium location at the northwest corner of the Roman Forum was later lost in the city's growth and development, but was rediscovered and excavated by archaeologists at the turn of the twentieth century. Some of Rome's earliest monuments; including the speaking platform known as the Rostra, the Columna Maenia, the Graecostasis and the Tabula Valeria were part of or associated with the Comitium.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly—almost to the point of unrecognisability—over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms from 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

The Philippics are a series of 14 speeches composed by Cicero in 44 and 43 BC, condemning Mark Antony. Cicero likened these speeches to those of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon; both Demosthenes’s and Cicero's speeches became known as Philippics. Cicero's Second Philippic is styled after Demosthenes' De Corona.

The Tribal Assembly was an assembly consisting of all Roman citizens convened by tribes (tribus).

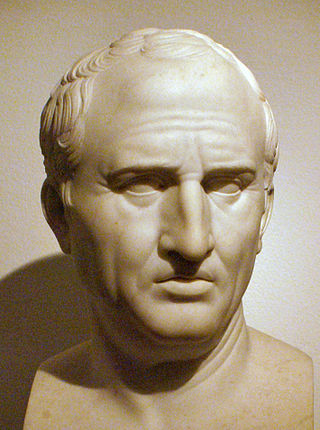

The writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero constitute one of the most renowned collections of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity. Cicero was a Roman politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, philosopher, and constitutionalist who lived during the years of 106–43 BC. He held the positions of Roman senator and Roman consul (chief-magistrate) and played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He was extant during the rule of prominent Roman politicians, such as those of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marc Antony. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

In Roman constitutional law, rogatio is the term for a legislative bill placed before an Assembly of the People in ancient Rome. The rogatio procedure underscores the fact that the Roman Senate could issue decrees, but was not a legislative or parliamentarian body. Only the People could pass legislation.

Catherine Elizabeth Wannan Steel, is a British classical scholar. She is Professor of Classics at the University of Glasgow. Steel is an expert on the Roman Republic, the writings of Cicero, and Roman oratory.

Annales is the name of a fragmentary Latin epic poem written by the Roman poet Ennius in the 2nd century BC. While only snippets of the work survive today, the poem's influence on Latin literature was significant. Although written in Latin, stylistically it borrows from the Greek poetic tradition, particularly the works of Homer, and is written in dactylic hexameter. The poem was significantly larger than others from the period, and eventually comprised 18 books.

The lex Cassia de senatu was a Roman law, introduced in 104 BC by the tribune L. Cassius Longinus. The law excluded from the senate individuals who had been deprived of imperium by popular vote or had been convicted of a crime in a popular assembly.

The ballot laws of the Roman Republic were four laws which introduced the secret ballot to all popular assemblies in the Republic. They were all introduced by tribunes, and consisted of the lex Gabinia tabellaria of 139 BC, applying to the election of magistrates; the lex Cassia tabellaria of 137 BC, applying to juries except in cases of treason; the lex Papiria of 131 BC, applying to the passing of laws; and the lex Caelia of 107 BC, which expanded the lex Cassia to include matters of treason. Prior to the ballot laws, voters announced their votes orally to a teller, essentially making every vote public. The ballot laws curtailed the influence of the aristocratic class and expanded the freedom of choice for voters. Elections became more competitive. In short, the secret ballot made bribery more difficult.

Lucius Vettius was a Roman equestrian informer who informed on the Second Catilinarian conspiracy in 63 BC and later, in 59 BC, denounced a supposed plot of many conservative-leaning senators to murder Pompey. He was jailed and then found dead.

References

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Rome". Klio. 77: 205–206, 211–212.

- ↑ Van der Blom, Henriette (2016). Oratory and Political Career in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9781107280281.

- ↑ Tan, James (April 2008). "Contiones in the Age of Cicero". Classical Antiquity. 27: 163–166. doi:10.1525/ca.2008.27.1.163 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Pina Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Ancient Rome". Klio. 77: 205–206.

- ↑ Van der Blom, Henriette (2016). Oratory and Political Career in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9781107280281.

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in the Roman Republic". Klio. 77: 207.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (2009). Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–248. ISBN 9780511482878.

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Rome". Klio. 77: 207–208.

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Rome". Klio. 77: 209–211.

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Ancient Rome". Klio. 77: 207.

- ↑ Mouritsen, Henrik (2017). Politics in the Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9781139410861.

- ↑ Jehne, Martin (2013). "Feeding the Plebs with Words". In Steel, Catherine; Van der Blom, Henriette (eds.). Community and Communication: Oratory and Politics in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780199641895.

- ↑ Tan, James (April 2008). "Contiones in the Age of Cicero". Classical Antiquity. 27: 172–180 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Mouritsen, Henrik (2017). Politics in the Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–79. ISBN 9781139410861.

- ↑ Tan, James (April 2008). "Contiones in the Age of Cicero". Classical Antiquity. 27: 170 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Manuwald, Gesine (Spring 2012). "The speeches to the People in Cicero's oratorical corpora". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 30– via JSTOR.

- ↑ Jehne, Martin (2013). "Feeding the Plebs with Words: The Significance of Senatorial Public Oratory in The Small World of Roman Politics". In Steel, Catherine; Van der Blom, Henriëtte (eds.). Community and Communication: Oratory and Politics in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–58. ISBN 9780199641895.

- 1 2 Manuwald, Gesine (2018). Agrarian speeches: introduction, text, translation and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198715405.

- ↑ Manuwald, Gesine (Spring 2012). "The Speeches to the People in Cicero's oratorical corpora". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 30: 162–163 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Manuwald, Gesine (Spring 2012). "The Speeches to the People in Cicero's oratorical corpora". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 30: 165 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Watts, N. H. (1923). "The speeches delivered by Cicero after his return from exile: introduction". Cicero Volume XI. Loeb Classical Library (158). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780674991743.

- ↑ Manuwald, Gesine (Spring 2012). "The Speeches to the People in Cicero's oratorical corpora". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 30: 170–171 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Manuwald, Gesine (Spring 2012). "The Speeches to the People in Cicero's oratorical corpora". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 30: 172.

- ↑ Tan, James (April 2008). "Contiones in the Age of Cicero". Classical Antiquity. 27: 164 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Mouritsen, Henrik (2013). "From Meeting to Text: The Contio in the Late Republic". In Steel, Catherine; Van der Blom, Henriette (eds.). Community and Communication: Oratory and Politics in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–71. ISBN 9780199641895.

- ↑ Jehne, Martin (2013). "Feeding the Plebs with Words". In Steel, Catherine; Van der Blom, Henriette (eds.). Community and Communication: Oratory and Politics in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780199641895.

- ↑ Jehne, Martin (2013). "Feeding the Plebs with Words". In Steel, Catherine; Van der Blom, Henriette (eds.). Community and Communication: Oratory and Politics in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780199641895.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). "Contional ideology: the political drama". Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780511482878.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). "Contional ideology: the political drama". Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780511482878.

- ↑ Van der Blom, Henriette (2016). Oratory and Political Career in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9781107280281.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). "Contional ideology: the political drama". Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 9780511482878.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). "The Voice of the People". Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–143. ISBN 9780511482878.

- ↑ Pina-Polo, Francisco (1995). "Procedures and Functions of Civil and Military contiones in Rome". Klio. 77: 213–215.