Related Research Articles

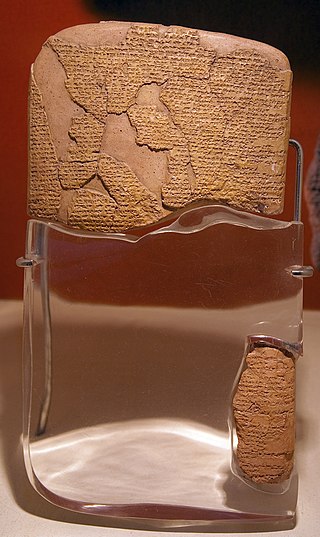

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written contract between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal persons.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. As of May 2023, 168 countries and the European Union are parties.

Resource depletion is the consumption of a resource faster than it can be replenished. Natural resources are commonly divided between renewable resources and non-renewable resources. The use of either of these forms of resources beyond their rate of replacement is considered to be resource depletion. The value of a resource is a direct result of its availability in nature and the cost of extracting the resource. The more a resource is depleted the more the value of the resource increases. There are several types of resource depletion, the most known being: Aquifer depletion, deforestation, mining for fossil fuels and minerals, pollution or contamination of resources, slash-and-burn agricultural practices, soil erosion, and overconsumption, excessive or unnecessary use of resources.

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) is an international agreement that regulates treaties among sovereign states.

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed regional seas and estuaries, rivers, lakes, groundwater systems (aquifers), and wetlands.

Water resources law is the field of law dealing with the ownership, control, and use of water as a resource. It is most closely related to property law, and is distinct from laws governing water quality.

The International Law Commission (ILC) is a body of experts responsible for helping develop and codify international law. It is composed of 34 individuals recognized for their expertise and qualifications in international law, who are elected by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) every five years.

The human right to water and sanitation (HRWS) is a principle stating that clean drinking water and sanitation are a universal human right because of their high importance in sustaining every person's life. It was recognized as a human right by the United Nations General Assembly on 28 July 2010. The HRWS has been recognized in international law through human rights treaties, declarations and other standards. Some commentators have based an argument for the existence of a universal human right to water on grounds independent of the 2010 General Assembly resolution, such as Article 11.1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); among those commentators, those who accept the existence of international ius cogens and consider it to include the Covenant's provisions hold that such a right is a universally binding principle of international law. Other treaties that explicitly recognize the HRWS include the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

The laws of state responsibility are the principles governing when and how a state is held responsible for a breach of an international obligation. Rather than set forth any particular obligations, the rules of state responsibility determine, in general, when an obligation has been breached and the legal consequences of that violation. In this way they are "secondary" rules that address basic issues of responsibility and remedies available for breach of "primary" or substantive rules of international law, such as with respect to the use of armed force. Because of this generality, the rules can be studied independently of the primary rules of obligation. They establish (1) the conditions of actions to qualify as internationally wrongful, (2) the circumstances under which actions of officials, private individuals and other entities may be attributed to the state, (3) general defences to liability and (4) the consequences of liability.

Global commons is a term typically used to describe international, supranational, and global resource domains in which common-pool resources are found. Global commons include the earth's shared natural resources, such as the high oceans, the atmosphere and outer space and the Antarctic in particular. Cyberspace may also meet the definition of a global commons.

War can heavily damage the environment, and warring countries often place operational requirements ahead of environmental concerns for the duration of the war. Some international law is designed to limit this environmental harm.

A reservation in international law is a caveat to a state's acceptance of a treaty. A reservation is defined by the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) as:

a unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a State, when signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or to modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State.

Water politics in the Jordan River basin refers to political issues of water within the Jordan River drainage basin, including competing claims and water usage, and issues of riparian rights of surface water along transnational rivers, as well as the availability and usage of ground water. Water resources in the region are scarce, and these issues directly affect the four political subdivisions located within and bordering the basin, which were created since the collapse, during World War I, of the former single controlling entity, the Ottoman Empire. Because of the scarcity of water and a unique political context, issues of both supply and usage outside the physical limits of the basin have been included historically.

The Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers is an international guideline regulating how rivers and their connected groundwaters that cross national boundaries may be used, adopted by the International Law Association (ILA) in Helsinki, Finland in August 1966. In spite of its adoption by the ILA, there is no mechanism in place that enforces the rules. Notwithstanding the guideline's lack of formal status, its work on rules governing international rivers was pioneering. It led to the creation of the United Nations' Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. In 2004, it was superseded by the Berlin Rules on Water Resources.

The Berlin Rules on Water Resources is a document adopted by the International Law Association (ILA) to summarize international law customarily applied in modern times to freshwater resources, whether within a nation or crossing international boundaries. Adopted on August 21, 2004, in Berlin, the document supersedes the ILA's earlier "The Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers", which was limited in its scope to international drainage basins and aquifers connected to them.

Water resource policy, sometimes called water resource management or water management, encompasses the policy-making processes and legislation that affect the collection, preparation, use, disposal, and protection of water resources. The long-term viability of water supply systems poses a significant challenge as a result of water resource depletion, climate change, and population expansion.

The Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, also known as the Water Convention, is an international environmental agreement and one of five UNECE's negotiated environmental treaties. The purpose of this convention is to improve national attempts and measures for protection and management of transboundary surface waters and groundwaters. On the international level, Parties are obliged to cooperate and create joint bodies. The Convention includes provisions on: monitoring, research, development, consultations, warning and alarm systems, mutual assistance and access as well as exchange of information.

International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) and its contract shows alignment with the UN Convention on international watercourses and has proven effective in its goals for the Rhine and the Rhine Basin. It was necessary for a treaty to come through the countries in the Rhine basin as it provides water based on industrial and agricultural needs and provides drinking water to over 20 million people.

UN General Assembly Resolution 60/147, the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law, is a United Nations Resolution about the rights of victims of international crimes. It was adopted by the General Assembly on 16 December 2005 in its 60th session. According to the preamble, the purpose of the Resolution is to assist victims and their representatives to remedial relief and to guide and encourage States in the implementation of public policies on reparations.

The Harmon Doctrine, or the doctrine of absolute territorial sovereignty, holds that a country has absolute sovereignty over the territory and resources within its borders.

References

- ↑ Current Status of Convention, United Nations

- ↑ "Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses: Entry into Force", 19 May 2014. treaties.un.org

- ↑ Raj, Krishna; Salman, Salman M.A. (1999). "International Groundwater Law and the World Bank Policy for Projects on Transboundary Groundwater". In Salman, Salman M. A. (ed.). Groundwater: Legal and Policy Perspectives : Proceedings of a World Bank Seminar. World Bank Publications. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8213-4613-6.

- ↑ Brahic, Catherine (8 November 2008). "Can legislation stop the wells running dry?". New Scientist (2681). doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(08)62793-1 . Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ McCaffrey, Stephen M. (1999). "International Groundwater Law: Evolution and Context". In Salman, Salman M. A. (ed.). Groundwater: Legal and Policy Perspectives : Proceedings of a World Bank Seminar. World Bank Publications. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8213-4613-6.

- 1 2 Dellapenna, Joseph W. "The Berlin rules on water resources: the new paradigm for international water law". Universidade do Algarve.[ dead link ]

- ↑ McCaffrey, Stephen. "Chapter 2: The UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. p. 17. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ "Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses" (PDF). United Nations. 1997. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- 1 2 McCaffrey, "Chapter 2: The UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses", 20-21.

- ↑ McCaffrey, "Chapter 2: The UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses", 21.