Related Research Articles

The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States is a treaty signed at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933, during the Seventh International Conference of American States. The Convention codifies the declarative theory of statehood as accepted as part of customary international law. At the conference, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull declared the Good Neighbor Policy, which opposed U.S. armed intervention in inter-American affairs. The convention was signed by 19 states. The acceptance of three of the signatories was subject to minor reservations. Those states were Brazil, Peru and the United States.

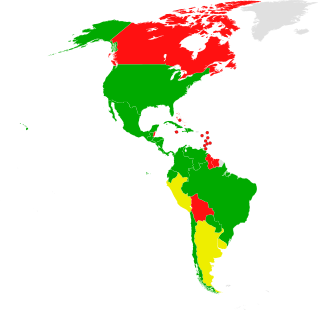

The Organization of American States, or the OAS or OEA, is an international organization that was founded on 30 April 1948 for the purposes of solidarity and co-operation among its member states within the Americas. Headquartered in the US capital, Washington, DC, the OAS has 35 members, which are independent states in the Americas. During the Cold War, the United States hoped the OAS would be a bulwark against the spread of communism. Since the 1990s, the organization has focused on election monitoring. The head of the OAS is the Secretary General; the incumbent is Uruguayan Luis Almagro.

The American Convention on Human Rights, also known as the Pact of San José, is an international human rights instrument. It was adopted by many countries in the Western Hemisphere in San José, Costa Rica, on 22 November 1969. It came into force after the eleventh instrument of ratification was deposited on 18 July 1978.

The Bancroft treaties, also called the Bancroft conventions, were a series of agreements made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries between the United States and other countries. They recognized the right of each party's nationals to become naturalized citizens of the other; and defined circumstances in which naturalized persons were legally presumed to have abandoned their new citizenship and resumed their old one.

Peruvian nationality law is regulated by the 1993 Constitution of Peru, the Nationality Law 26574 of 1996, and the Supreme Decree 010-2002-IN, which regulates the implementation of Law 26574. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Peru. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal membership in a nation, differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Peruvian nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Peru; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to at least one parent with Peruvian nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident, who has lived in Peru for a given period of time, through naturalization.

Sofía Álvarez Vignoli (1899-1986) was a Uruguayan jurist and briefly First Lady of Uruguay, who was active in the struggle to achieve Women's Suffrage.

Brazilian nationality law is based on both the principles of jus soli and of jus sanguinis. As a general rule, any person born in Brazil acquires Brazilian nationality at birth, irrespective of the status of parents. It may also be acquired by children born abroad of a Brazilian parent or by naturalization.

Doris Stevens was an American suffragist, woman's legal rights advocate and author. She was the first female member of the American Institute of International Law and first chair of the Inter-American Commission of Women.

Argentine nationality law regulates the manner in which one acquires, or is eligible to acquire, Argentine nationality. Nationality, as used in international law, describes the legal methods in which a person obtains a national identity and formal membership in a nation. Citizenship refers to the relationship between a nation and a national, after membership has been attained. Argentina recognizes a dual system accepting Jus soli and Jus sanguinis for acquisition of nationality by birth and allows foreign persons to naturalize.

Colombian nationality is typically obtained by birth in Colombia when one of the parents is either a Colombian national or a Colombian legal resident, by birth abroad when at least one parent was born in Colombia, or by naturalization, as defined by Article 96 of the Constitution of Colombia and the Law 43-1993 as modified by Legislative Act 1 of 2002. Colombian law differentiates between nationality and citizenship. Nationality is the attribute of the person in international law that describes their relationship to the State, whereas citizenship is given to those nationals that have certain rights and responsibilities to the State. Article 98 of the Colombian constitution establishes that Colombian citizens are those nationals that are 18 years of age or older. Colombian citizens are entitled to vote in elections and exercise the public actions provided in the constitution.

The Inter-American Commission of Women, abbreviated CIM, is an organization that falls within the Organization of American States. It was established in 1928 by the Sixth Pan-American Conference and is composed of one female representative from each Republic in the Union. In 1938, the CIM was made a permanent organization, with the goal of studying and addressing women's issues in the Americas.

Marta Vergara Varas was a Chilean author, editor, journalist and women's rights activist. Introduced to international feminism in 1930, she became instrumental in the development of the Inter-American Commission of Women (CIM) helping gather documentation on laws which effected women's nationality. She pushed Doris Stevens to broaden the scope of international feminism to include working women's issues in the quest for equality. A founding member of the Pro-Emancipation Movement of Chilean Women, she was editor of its monthly bulletin La Mujer Nueva. When she was ousted from the Communist Party she moved to Europe and worked as a journalist during the war. At war's end, she returned to Washington, D.C. and worked at the CIM continuing to press for women's suffrage and equality, before returning to Chile, where she resumed her writing career.

Guatemalan nationality law is regulated by the 1985 Constitution, as amended in 1995, and the 1966 Nationality Law, as amended in 1996. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Guatemala. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Guatemalan nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Guatemala; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to at least one parent with Guatemalan nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in Guatemala for a given period of time through naturalization.

Nicaraguan nationality law is regulated by the Constitution, the General Law for Migration and Foreigners, Law No. 761 and relevant treaties to which Nicaragua is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Nicaragua. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nicaraguan nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Nicaragua; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Nicaraguan nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization or for a foreigner who has provided exceptional service to the nation.

Bolivian nationality law is regulated by the 2009 Constitution. This statute determines who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Bolivia. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Bolivian nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Bolivia; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to at least one parent with Bolivian nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in Bolivia for a given period of time through naturalization.

Cuban nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Cuba, currently the 2019 Constitution, and to a limited degree upon Decree 358 of 1944. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Cuba. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Cuban nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Cuba; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Cuban nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Dominican Republic nationality law is regulated by the 2015 Constitution, Law 1683 of 1948, the 2014 Naturalization Law #169-14, and relevant treaties to which the Dominican Republic is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of the Dominican Republic. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality in the Dominican Republic is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in the Dominican Republic; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Dominican nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization or for a foreigner who has provided exceptional service to the nation.

Salvadoran nationality law is regulated by the Constitution; the Legislative Decree 2772, commonly known as the 1933 Law on Migration, and its revisions; and the 1986 Law on Foreigner Issues. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of El Salvador. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Salvadoran nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in El Salvador; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Salvadoran nationality. It can also be granted to a citizen of any Central American state, or a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Honduran nationality law is regulated by the Constitution, the Migration and Aliens Act, the 2014 Law on Protection of Honduran Migrants and their Families and relevant treaties to which Honduras is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Honduras. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Honduran nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Honduras; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Honduran nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Panamanian nationality law is regulated by the 1972 Constitution, as amended by legislative acts; the Civil Code; migration statues, such as Law Decree No. 3 of 2008; and relevant treaties to which Panama is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a citizen of Panama. The legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation differ from the relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Panamanian nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Panama; or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth abroad to a parent with Panamanian nationality. It can also be granted to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

References

- 1 2 3 "The World's First Treaty of Equality for Women - Montevideo, Uruguay, 1933". Organization of American States. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Commission of Women. 1933. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Convention on the Nationality of Women (Inter-American); December 26, 1933". Avalon Project . New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Law School. December 26, 1933. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- 1 2 Freeman, Rudolf & Chinkin 2012, p. 235.

- 1 2 Green 1956, p. 750.

- ↑ Phayre, Ignatius (1 May 1921). "A Woman Don Quixote in the Harems of Spain". The New York Times Book Review and Magazine . New York City, New York. Retrieved 28 February 2016– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Convention on the Nationality of Women". Organization of American States. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Commission of Women. 26 December 1933. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.