El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador's capital and largest city is San Salvador. The country's population in 2023 was estimated to be 6.5 million.

The history of El Salvador begins with several distinct groups of Mesoamerican people, especially the Pipil, the Lenca and the Maya. In the early 16th century, the Spanish Empire conquered the territory, incorporating it into the Viceroyalty of New Spain ruled from Mexico City. In 1821, El Salvador achieved independence from Spain as part of the First Mexican Empire, only to further secede as part of the Federal Republic of Central America two years later. Upon the republic's independence in 1841, El Salvador became a sovereign state until forming a short-lived union with Honduras and Nicaragua called the Greater Republic of Central America, which lasted from 1895 to 1898.

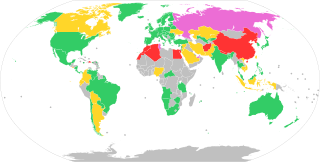

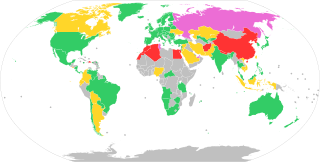

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is an index that ranks countries "by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys." The CPI generally defines corruption as an "abuse of entrusted power for private gain". The index is published annually by the non-governmental organisation Transparency International since 1995.

Carlos Mauricio Funes Cartagena is a Salvadoran politician and former journalist who served as the 41st President of El Salvador from 2009 to 2014. Funes won the 2009 presidential election as the candidate of the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) party and took office on 1 June 2009. Since 2014, Funes and his immediate family have been living in exile in Nicaragua due to allegations of criminality during his tenure. In July 2023, he was placed under sanctions by the U.S. State Department due to his conviction in absentia for negotiations related to the gang truces he made while in office, illicit enrichment, and tax evasion.

Observers maintain that corruption in Paraguay remains a major impediment to the emergence of stronger democratic institutions and sustainable economic development in Paraguay.

Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez is a Salvadoran politician and businessman who is the 43rd president of El Salvador, serving since 1 June 2019. He is the first Salvadoran president since 1984 who was not elected as a candidate of one of the country's two major political parties: the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), of which Bukele was formerly a member.

Nuevas Ideas is a Salvadoran political party. The party was founded on 25 October 2017 by Nayib Bukele, the then-mayor of San Salvador, and was registered by the Supreme Electoral Court on 21 August 2018. The party's current president is Xavier Zablah Bukele, a cousin of Bukele who has served since March 2020.

The 2020 Salvadoran political crisis, commonly referred to in El Salvador as the numeronym 9F or El Bukelazo, was an incident in El Salvador on 9 February 2020. During the political crisis, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele sent 40 soldiers of the Salvadoran Army into the Legislative Assembly building in an effort to coerce politicians to approve a loan request of 109 million dollars from the United States for Bukele's security plan for the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic in El Salvador was a part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus was confirmed to have reached El Salvador on 18 March 2020. As of 19 September 2021, El Salvador reported 102,024 cases, 3,114 deaths, and 84,981 recoveries. As of that date El Salvador had arrested a total of 2,424 people for violating quarantine orders, and 1,268,090 people had been tested for the virus. On 31 March 2020, the first COVID-19 death in El Salvador was confirmed.

Events in the year 2020 in El Salvador.

David Victoriano Munguía Payés is a former Salvadoran Army general who served as Minister of National Defense of El Salvador from 2009 to 2011 and again from 2013 to 2019.

José Alejandro Zelaya Villalobo is a Salvadoran politician. He served as Minister of Finance in the cabinet of President Nayib Bukele from 2020 to 2023.

Ernesto Alfredo Castro Aldana is a Salvadoran politician and businessman who currently serves as the president of the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador. Castro previously served as a secretary and private advisor to Nayib Bukele from 2012 to 2020 when he was elected as a deputy of the Legislative Assembly from San Salvador in the 2021 legislative election.

El Salvador became the first country in the world to use bitcoin as legal tender, after having been adopted as such by the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador in 2021. It has been promoted by Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, who claimed that it would improve the economy by making banking easier for Salvadorans, and that it would encourage foreign investment. The adoption has been criticized both internationally and within El Salvador, due to the volatility of Bitcoin, its environmental impact, and lack of transparency regarding the government's fiscal policy.

The Salvadoran gang crackdown, referred to in El Salvador as the régimen de excepción and the guerra contra las pandillas, began in March 2022 in response to a crime spike between 25 and 27 March 2022, when 87 people were killed in El Salvador. The Salvadoran government blamed the spike in murders on criminal gangs in the country, resulting in the country's legislature approving a state of emergency that suspended the rights of association and legal counsel, and increased the time spent in detention without charge, among other measures that expanded the powers of law enforcement in the country.

Opinion polling has been conducted in El Salvador since September 2019, three months after President Nayib Bukele took office on 1 June 2019, to gauge public opinion of Bukele and his government. Despite negative reception from outside of El Salvador, domestically, Bukele is considered to be one of the most popular presidents in Salvadoran history as his approval ratings generally hover around 90 percent.

The Terrorism Confinement Center is a maximum security prison located in Tecoluca, San Vicente, El Salvador. The prison was built from July 2022 to January 2023 amidst a large-scale gang crackdown; it was opened in January 2023 by President Nayib Bukele and received its first 2,000 prisoners in February 2023.

Osiris Luna Meza is a Salvadoran politician who currently serves as the General Director of Penal Centers and the Vice Minister of Justice and Public Security. He previously served as a deputy of the Legislative Assembly from the department of San Salvador from 2018 to 2019.

The Territorial Control Plan is an ongoing Salvadoran security and anti-gang program. The program consists of six phases and a potential seventh phase if phases one through six are unsuccessful. In 2019, the Salvadoran government estimated that the Territorial Control Plan would cost US$575.2 million in total.

Jorge Alejandro Muyshondt Álvarez was a Salvadoran politician who served as a national security advisor to Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele from 2019 to 2023. Muyshondt previously served as Bukele's security advisor from 2017 to 2019 while Bukele was mayor of San Salvador.