In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. The term is similar to the idea of a senate, synod or congress and is commonly used in countries that are current or former monarchies. Some contexts restrict the use of the word parliament to parliamentary systems, although it is also used to describe the legislature in some presidential systems, even where it is not in the official name.

Absolute monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitution may exist in some countries. These are often hereditary monarchies. On the other hand, in constitutional monarchies, in which the authority of the head of state is also bound or restricted by the constitution, a legislature, or unwritten customs, the king or queen is not the only one to decide, and their entourage also exercises power, mainly the prime minister.

On 20 June 1789, the members of the French Third Estate took the Tennis Court Oath in the tennis court which had been built in 1686 for the use of the Versailles palace. Their vow "not to separate and to reassemble wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established" became a pivotal event in the French Revolution.

In France under the Ancien Régime, the Estates General or States-General was a legislative and consultative assembly of the different classes of French subjects. It had a separate assembly for each of the three estates, which were called and dismissed by the king. It had no true power in its own right as, unlike the English Parliament, it was not required to approve royal taxation or legislation. It served as an advisory body to the king, primarily by presenting petitions from the various estates and consulting on fiscal policy.

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and evolved over time.

This is a glossary of the French Revolution. It generally does not explicate names of individual people or their political associations; those can be found in List of people associated with the French Revolution.

There is significant disagreement among historians of the French Revolution as to its causes. Usually, they acknowledge the presence of several interlinked factors, but vary in the weight they attribute to each one. These factors include cultural changes, normally associated with the Enlightenment; social change and financial and economic difficulties; and the political actions of the involved parties. For centuries, the French society was divided into three estates or orders.

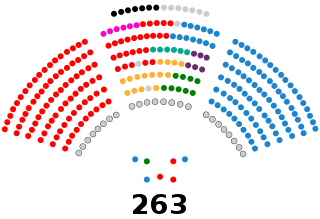

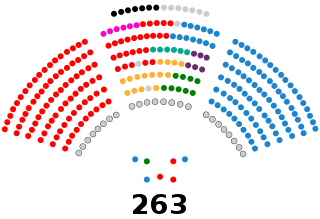

The Cortes Generales are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies, and the Senate.

The Estates General of 1789(French: États Généraux de 1789) was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom of France. Summoned by King Louis XVI, the Estates General of 1789 ended when the Third Estate formed the National Assembly and, against the wishes of the King, invited the other two estates to join. This signaled the outbreak of the French Revolution.

Absolute monarchy in France slowly emerged in the 16th century and became firmly established during the 17th century. Absolute monarchy is a variation of the governmental form of monarchy in which the monarch holds supreme authority and where that authority is not restricted by any written laws, legislature, or customs. In France, Louis XIV was the most famous exemplar of absolute monarchy, with his court central to French political and cultural life during his reign. It ended in May 1789, when widespread social distress led to the convocation of the Estates-General, which was converted into a National Assembly in June. The Assembly passed a series of radical measures, including the abolition of feudalism, state control of the Catholic Church and extending the right to vote.

The Nobles of the Sword were the noblemen of the oldest class of nobility in France dating from the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, and arguably still in existence by descent. It was originally the knightly class, owing military service in return for the possession of feudal landed estates. They played an important part during the French revolution since their attempts to retain their old power monopoly caused the new nobility’s interests to align with the newly arising French bourgeoisie class, creating a powerful force for change in French society in the late 18th century. For the year 1789, Gordon Wright gives a figure of 80,000 nobles.

An Assembly of Notables was a group of high-ranking nobles, ecclesiastics, and state functionaries convened by the King of France on extraordinary occasions to consult on matters of state. Assemblymen were prominent men, usually of the aristocracy, and included royal princes, peers, archbishops, high-ranking judges, and, in some cases, major town officials. The king would issue one or more reforming edicts after hearing their advice.

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then Castilian king, Ferdinand III, to the vacant Leonese throne. It continued to exist as a separate entity after the personal union in 1469 of the crowns of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs up to the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1715.

The Cortes of León or Decreta of León from year 1188 was a parliamentary body in the medieval Kingdom of León. According to UNESCO it is the first documented example of parliamentarism in history.

The assembly of the French clergy was in its origins a representative meeting of the Catholic clergy of France, held every five years, for the purpose of apportioning the financial burdens laid upon the clergy of the French Catholic Church by the kings of France. Meeting from 1560 to 1789, the Assemblies ensured to the clergy an autonomous financial administration, by which they defended themselves against taxation.

The Portuguese royal court transferred from Lisbon to the Portuguese colony of Brazil in a strategic retreat of Queen Maria I of Portugal, Prince Regent John, the Braganza royal family, its court, and senior functionaries, totaling nearly 10,000 people, on 27 November 1807. The embarkment took place on the 27th, but due to weather conditions, the ships were only able to depart on the 29 November. The Braganza royal family departed for Brazil just days before Napoleonic forces invaded Portugal on 1 December 1807. The Portuguese crown remained in Brazil from 1808 until the Liberal Revolution of 1820 led to the return of John VI of Portugal on 26 April 1821.

The Cortes of Aragon is the regional parliament for the Spanish autonomous community of Aragon. The Cortes traces its history back to meetings summoned by the Kings of Aragon which began in 1162. Abolished in 1707, the Cortes was revived in 1983 following the passing of a Statute of Autonomy.

In the Medieval Kingdom of Portugal, the Cortes was an assembly of representatives of the estates of the realm – the nobility, clergy and bourgeoisie. It was called and dismissed by the King of Portugal at will, at a place of his choosing. Cortes which brought all three estates together are sometimes distinguished as Cortes-Gerais, in contrast to smaller assemblies which brought only one or two estates, to negotiate a specific point relevant only to them.

The Portuguese nobility was a social class enshrined in the laws of the Kingdom of Portugal with specific privileges, prerogatives, obligations and regulations. The nobility ranked immediately after royalty and was itself subdivided into a number of subcategories which included the titled nobility and nobility of blood at the top and civic nobility at the bottom, encompassing a small, but not insignificant proportion of Portugal's citizenry.

The Polysynodial System or Polysynodial Regime or System of Councils was the way of organization of the composite monarchy ruled by the Catholic Monarchs and the Spanish Habsburgs, which entrusted the central administration in a group of collegiate bodies (councils) already existing or created ex novo. Most of the councils were formed by lawyers trained in academic study of Roman law. After its creation in 1521, the Council of State, chaired by the monarch and formed by the high nobility and clergy, became the supreme body of the monarchy. The polysynodial system met its demise in the early 18th century in the wake of the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by the incoming Bourbon dynasty, which organized a system underpinned by Secretaries of State.