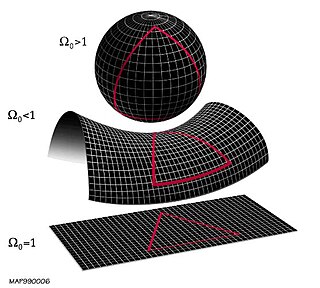

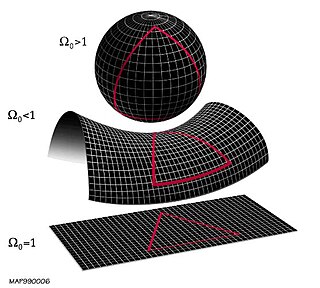

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the earliest known periods through its subsequent large-scale form. These models offer a comprehensive explanation for a broad range of observed phenomena, including the abundance of light elements, the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, and large-scale structure. The overall uniformity of the Universe, known as the flatness problem, is explained through cosmic inflation: a sudden and very rapid expansion of space during the earliest moments. However, physics currently lacks a widely accepted theory of quantum gravity that can successfully model the earliest conditions of the Big Bang.

Physical cosmology is a branch of cosmology concerned with the study of cosmological models. A cosmological model, or simply cosmology, provides a description of the largest-scale structures and dynamics of the universe and allows study of fundamental questions about its origin, structure, evolution, and ultimate fate. Cosmology as a science originated with the Copernican principle, which implies that celestial bodies obey identical physical laws to those on Earth, and Newtonian mechanics, which first allowed those physical laws to be understood.

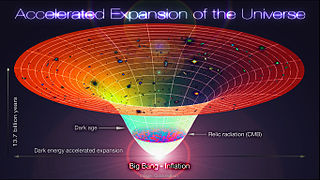

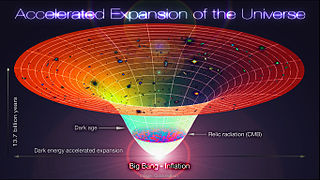

In physical cosmology, cosmic inflation, cosmological inflation, or just inflation, is a theory of exponential expansion of space in the early universe. The inflationary epoch lasted from 10−36 seconds after the conjectured Big Bang singularity to some time between 10−33 and 10−32 seconds after the singularity. Following the inflationary period, the universe continued to expand, but at a slower rate. The acceleration of this expansion due to dark energy began after the universe was already over 7.7 billion years old.

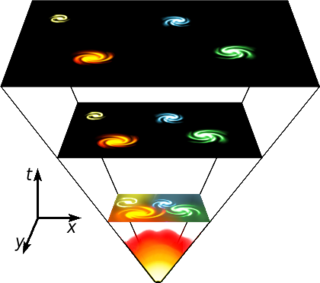

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. According to this theory, space and time emerged together 13.787±0.020 billion years ago, and the universe has been expanding ever since the Big Bang. While the spatial size of the entire universe is unknown, it is possible to measure the size of the observable universe, which is approximately 93 billion light-years in diameter at the present day.

Observations show that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, such that the velocity at which a distant galaxy recedes from the observer is continuously increasing with time. The accelerated expansion of the universe was discovered during 1998 by two independent projects, the Supernova Cosmology Project and the High-Z Supernova Search Team, which both used distant type Ia supernovae to measure the acceleration. The idea was that as type Ia supernovae have almost the same intrinsic brightness, and since objects that are further away appear dimmer, we can use the observed brightness of these supernovae to measure the distance to them. The distance can then be compared to the supernovae's cosmological redshift, which measures how much the universe has expanded since the supernova occurred; the Hubble law established that the further an object is from us, the faster it is receding. The unexpected result was that objects in the universe are moving away from one another at an accelerated rate. Cosmologists at the time expected that recession velocity would always be decelerating, due to the gravitational attraction of the matter in the universe. Three members of these two groups have subsequently been awarded Nobel Prizes for their discovery. Confirmatory evidence has been found in baryon acoustic oscillations, and in analyses of the clustering of galaxies.

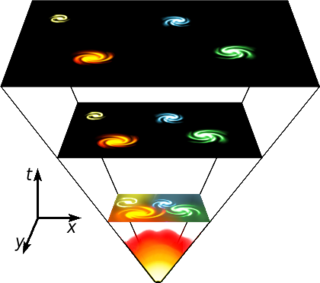

In standard cosmology, comoving distance and proper distance are two closely related distance measures used by cosmologists to define distances between objects. Proper distance roughly corresponds to where a distant object would be at a specific moment of cosmological time, which can change over time due to the expansion of the universe. Comoving distance factors out the expansion of the universe, giving a distance that does not change in time due to the expansion of space.

The ultimate fate of the universe is a topic in physical cosmology, whose theoretical restrictions allow possible scenarios for the evolution and ultimate fate of the universe to be described and evaluated. Based on available observational evidence, deciding the fate and evolution of the universe has become a valid cosmological question, being beyond the mostly untestable constraints of mythological or theological beliefs. Several possible futures have been predicted by different scientific hypotheses, including that the universe might have existed for a finite and infinite duration, or towards explaining the manner and circumstances of its beginning.

The Big Crunch is a hypothetical scenario for the ultimate fate of the universe, in which the expansion of the universe eventually reverses and the universe recollapses, ultimately causing the cosmic scale factor to reach zero, an event potentially followed by a reformation of the universe starting with another Big Bang. The vast majority of evidence indicates that this hypothesis is not correct. Instead, astronomical observations show that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, rather than being slowed by gravity, suggesting that the universe is far more likely to end in heat death.

A non-standard cosmology is any physical cosmological model of the universe that was, or still is, proposed as an alternative to the then-current standard model of cosmology. The term non-standard is applied to any theory that does not conform to the scientific consensus. Because the term depends on the prevailing consensus, the meaning of the term changes over time. For example, hot dark matter would not have been considered non-standard in 1990, but would be in 2010. Conversely, a non-zero cosmological constant resulting in an accelerating universe would have been considered non-standard in 1990, but is part of the standard cosmology in 2010.

The particle horizon is the maximum distance from which light from particles could have traveled to the observer in the age of the universe. Much like the concept of a terrestrial horizon, it represents the boundary between the observable and the unobservable regions of the universe, so its distance at the present epoch defines the size of the observable universe. Due to the expansion of the universe, it is not simply the age of the universe times the speed of light, but rather the speed of light times the conformal time. The existence, properties, and significance of a cosmological horizon depend on the particular cosmological model.

A de Sitter universe is a cosmological solution to the Einstein field equations of general relativity, named after Willem de Sitter. It models the universe as spatially flat and neglects ordinary matter, so the dynamics of the universe are dominated by the cosmological constant, thought to correspond to dark energy in our universe or the inflaton field in the early universe. According to the models of inflation and current observations of the accelerating universe, the concordance models of physical cosmology are converging on a consistent model where our universe was best described as a de Sitter universe at about a time seconds after the fiducial Big Bang singularity, and far into the future.

In physical cosmology, the age of the universe is the time elapsed since the Big Bang. Today, astronomers have derived two different measurements of the age of the universe: a measurement based on direct observations of an early state of the universe, which indicate an age of 13.772±0.020 billion years as interpreted with the Lambda-CDM concordance model as of 2018; and a measurement based on the observations of the local, modern universe, which suggest a younger age. The uncertainty of the first kind of measurement has been narrowed down to 20 million years, based on a number of studies which all gave extremely similar figures for the age. These include studies of the microwave background radiation by the Planck spacecraft, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and other space probes. Measurements of the cosmic background radiation give the cooling time of the universe since the Big Bang, and measurements of the expansion rate of the universe can be used to calculate its approximate age by extrapolating backwards in time. The range of the estimate is also within the range of the estimate for the oldest observed star in the universe.

The ΛCDM or Lambda-CDM model is a parameterization of the Big Bang cosmological model in which the universe contains three major components: first, a cosmological constant denoted by Lambda associated with dark energy; second, the postulated cold dark matter ; and third, ordinary matter. It is frequently referred to as the standard modelof Big Bang cosmology because it is the simplest model that provides a reasonably good account of the following properties of the cosmos:

The flatness problem is a cosmological fine-tuning problem within the Big Bang model of the universe. Such problems arise from the observation that some of the initial conditions of the universe appear to be fine-tuned to very 'special' values, and that small deviations from these values would have extreme effects on the appearance of the universe at the current time.

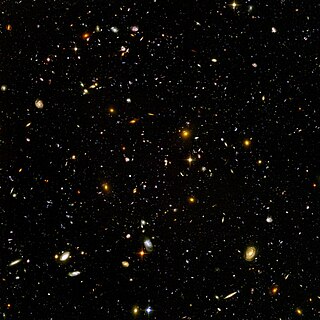

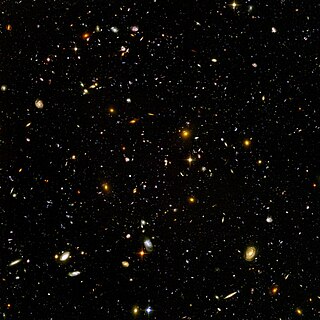

In physical cosmology, structure formation is the formation of galaxies, galaxy clusters and larger structures from small early density fluctuations. The universe, as is now known from observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation, began in a hot, dense, nearly uniform state approximately 13.8 billion years ago. However, looking at the night sky today, structures on all scales can be seen, from stars and planets to galaxies. On even larger scales, galaxy clusters and sheet-like structures of galaxies are separated by enormous voids containing few galaxies. Structure formation attempts to model how these structures were formed by gravitational instability of small early ripples in spacetime density or another emergence.

The history of the Big Bang theory began with the Big Bang's development from observations and theoretical considerations. Much of the theoretical work in cosmology now involves extensions and refinements to the basic Big Bang model. The theory itself was originally formalised by Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and professor of physics Georges Lemaître. Hubble's Law of the expansion of the universe provided foundational support for the theory.

A cosmological horizon is a measure of the distance from which one could possibly retrieve information. This observable constraint is due to various properties of general relativity, the expanding universe, and the physics of Big Bang cosmology. Cosmological horizons set the size and scale of the observable universe. This article explains a number of these horizons.

The expansion of the universe is the increase in distance between any two given gravitationally unbound parts of the observable universe with time. It is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. The universe does not expand "into" anything and does not require space to exist "outside" it. This expansion involves neither space nor objects in space "moving" in a traditional sense, but rather it is the metric that changes in scale. As the spatial part of the universe's spacetime metric increases in scale, objects become more distant from one another at ever-increasing speeds. To any observer in the universe, it appears that all of space is expanding, and that all but the nearest galaxies recede at speeds that are proportional to their distance from the observer. While objects within space cannot travel faster than light, this limitation does not apply to the effects of changes in the metric itself. Objects that recede beyond the cosmic event horizon will eventually become unobservable, as no new light from them will be capable of overcoming the universe's expansion, limiting the size of our observable universe.

The Milne model was a special-relativistic cosmological model proposed by Edward Arthur Milne in 1935. It is mathematically equivalent to a special case of the FLRW model in the limit of zero energy density and it obeys the cosmological principle. The Milne model is also similar to Rindler space, a simple re-parameterization of flat Minkowski space.

Particle physics is the study of the interactions of elementary particles at high energies, whilst physical cosmology studies the universe as a single physical entity. The interface between these two fields is sometimes referred to as particle cosmology. Particle physics must be taken into account in cosmological models of the early universe, when the average energy density was very high. The processes of particle pair production, scattering and decay influence the cosmology.