Related Research Articles

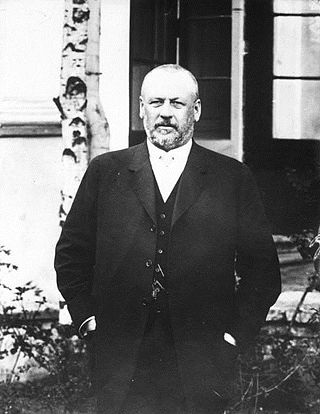

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte, also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the emperor as head of government. Neither liberal nor conservative, he attracted foreign capital to boost Russia's industrialization. Witte's strategy was to avoid the danger of wars.

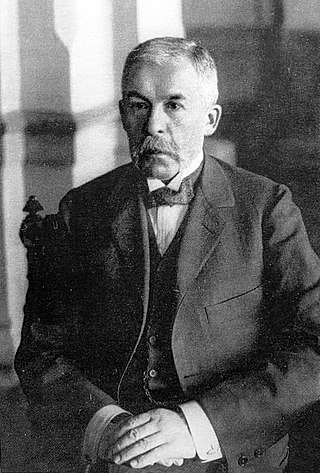

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin was a Russian statesman who served as the third prime minister and the interior minister of the Russian Empire from 1906 until his assassination in 1911. Known as the greatest reformer of Russian society and economy, his reforms caused unprecedented growth of the Russian state, which was halted by his assassination.

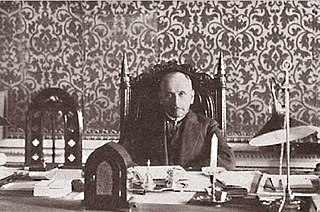

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank of Active Privy Councillor, 1st class. During his time in government, Goremykin pursued conservative policies.

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Constitutional Democratic party. He changed his view on the monarchy between 1905 and 1917. In the Russian Provisional Government, he served as Foreign Minister, working to prevent Russia's exit from the First World War.

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a member of the Russian Assembly and served as prime minister in 1916. A confidante of the Empress Alexandra, under his administration the country suffered drastic inflation and a transportation breakdown, which led to severe food shortages. Stürmer simply let matters drift until he was able to be relieved of this post. He was during the course of his career Minister of Internal Affairs and Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire.

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, and an advocate of moderate reforms opposed to the influence of Grigori Rasputin.

Prince Nikolai Dmitriyevich Golitsyn was a Russian aristocrat, monarchist and the last prime minister of Imperial Russia. He was in office from 29 December 1916 (O.S.) or 9 January 1917 (N.S.) until his government resigned after the outbreak of the February Revolution.

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko was a Russian statesman of Ukrainian origin. Known for his colorful language and conservative politics, he was the State Councillor and chamberlain of the Imperial family, Chairman of the State Duma and one of the leaders of the February Revolution of 1917, during which he headed the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. He was a key figure in the events that led to the abdication of Nicholas II of Russia on 15 March 1917.

Pyotr Nikolayevich Durnovo was an Imperial Russian lawyer, politician, and member of Russian nobility belonged to House of Durnovo. Known by anti-Tsarist revolutionaries in the era of the Russian Revolution of 1905 as "the counter-revolution's butcher."

Nikolai Nikolayevich Pokrovsky was a (nationalist) Russian politician and the last foreign minister of the Russian Empire.

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and one of the leaders of the Constitutional Democratic Party, notable for his advocacy of a constitutional Russian state. He served as deputy in the (radical) Second, and conservative Third and Fourth State Duma. According to Stephen F. Williams Maklakov is "an inviting lens to which to view at the last years of Tsarism".

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov was a Russian publicist and politician who served as the interior minister from September 1916 to February 1917.

Aleksey Nikolayevich Khvostov was a right-wing Russian politician and the leader of the Russian Assembly. He was a governor, a Privy Councillor (Russia), a chamberlain, a member of the Black Hundreds, and anti-German. He supported the Union of the Russian People. He was Minister of Interior for five months, opposed constitutional reforms and publicly accused Rasputin of spying for Germany. He had to resign after he planned to secretly have him eliminated.

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the legislature in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Tauride Palace in Saint Petersburg. It convened four times between 27 April 1906 and the collapse of the empire in February 1917. The first and the second dumas were more democratic and represented a greater number of national types than their successors. The third duma was dominated by gentry, landowners, and businessmen. The fourth duma held five sessions; it existed until 2 March 1917, and was formally dissolved on 6 October 1917.

The Progressive Bloc was an alliance of political forces in the Russian Empire and occupied 236 of the 442 seats in the Imperial Duma.

The February Revolution, known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution, was the first of two revolutions which took place in Russia in 1917.

The Council of Ministers of the Russian Empire was the highest executive authority of the Russian Empire, created in a new form by the highest decree of October 19, 1905 for the general "management and unification of the actions of the chief heads of departments on subjects of both legislation and higher state administration". The ministers ceased to be separate officials, responsible to the emperor, each only for their actions and orders.

Anatoly Anatolyevich Neratov was a Russian diplomat and an official of the Russian foreign ministry. He was deputy to five foreign ministers of the Tsarist and the Provisional Government.

An index of articles related to the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War period (1905–1922). It covers articles on topics, events, and persons related to the revolutionary era, from the 1905 Russian Revolution until the end of the Russian Civil War. The See also section includes other lists related to Revolutionary Russia and the Soviet Union, including an index of articles about the Soviet Union (1922–1991) which is the next article in this series, and Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War.

References

- ↑ M. Cherniasvsky (1967) Prologue to Revolution, p. 3

- 1 2 Sergei V. Kulikov (2012) Emperor Nicholas II and the State Duma Unknown Plans and Missed Opportunities, p. 48-49. In: Russian Studies in History, vol. 50, no. 4

- ↑ Figes, pp. 270, 275.

- ↑ D.C.B. Lieven (1983) Russia and the Origins of the First World War, p. 56

- ↑ Porter, T. (2003). Russian History, 30(3), 348-350. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24660814

- ↑ Antrick, p. 79, 117.

- ↑ P.N. Milyukov (1921) The Russian Revolution. Vol I: The Revolution divided, p. 15

- ↑ The PENULTIMATE PRIME Minister of the RUSSIAN EMPIRE A. F. TREPOV by FEDOR ALEKSANDROVICH GAIDA (2012)

- ↑ The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra. April 1914-March 1917, p. 317. By Joseph T. Fuhrmann, ed.; Smith, p. 485.

- 1 2 Frank Alfred Golder (1927) Documents of Russian History 1914–1917. Read Books. ISBN 1443730297.

- ↑ "Boris Sturmer : Biography". www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- 1 2 P.N. Milyukov (1921), p. 16

- ↑ Peeling, Siobhan: Shti︠u︡rmer, Boris Vladimirovich, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-12-16. DOI: .

- ↑ V. Chernov, p. 21

- ↑ The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra. April 1914-March 1917, p. 5. by Joseph T. Fuhrmann, ed.

- ↑ P.N. Milyukov (1921), p. 19

- ↑ Moe, p. 438.

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker (2013) The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 549. ISBN 1135506949

- ↑ Der Zar, Rasputin und die Juden, p. 39

- ↑ Moe, p. 471.

- ↑ George Buchanan (1923) My mission to Russia and other diplomatic memories

- ↑ Leonid Katsis and Helen Tolstoy (2013) Jewishness in Russian Culture: Within and Without. BRILL. p. 156. ISBN 9004261621

- ↑ THE GREAT RUSSIAN REVOLUTION BY VICTOR CHERNOV, p. 20