Related Research Articles

The courts of England and Wales, supported administratively by His Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service, are the civil and criminal courts responsible for the administration of justice in England and Wales.

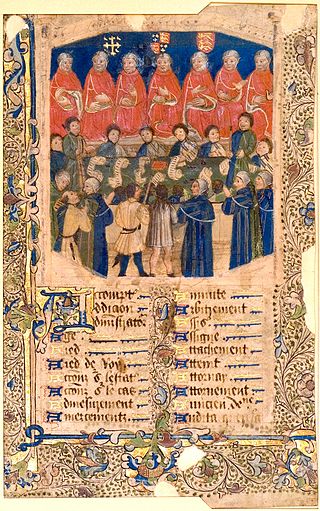

The Exchequer of Pleas, or Court of Exchequer, was a court that dealt with matters of equity, a set of legal principles based on natural law and common law in England and Wales. Originally part of the curia regis, or King's Council, the Exchequer of Pleas split from the curia in the 1190s to sit as an independent central court. The Court of Chancery's reputation for tardiness and expense resulted in much of its business transferring to the Exchequer. The Exchequer and Chancery, with similar jurisdictions, drew closer together over the years until an argument was made during the 19th century that having two seemingly identical courts was unnecessary. As a result, the Exchequer lost its equity jurisdiction. With the Judicature Acts, the Exchequer was formally dissolved as a judicial body by an Order in Council on 16 December 1880.

A high sheriff is a ceremonial officer for each shrieval county of England and Wales and Northern Ireland or the chief sheriff of a number of paid sheriffs in U.S. states who outranks and commands the others in their court-related functions. In Canada, the High Sheriff provides administrative services to the supreme and provincial courts.

The word prothonotary is recorded in English since 1447, as "principal clerk of a court," from L.L. prothonotarius, from Greek protonotarios "first scribe," originally the chief of the college of recorders of the court of the Byzantine Empire, from Greek πρῶτοςprotos "first" + Latin notarius ("notary"); the -h- appeared in Medieval Latin. The title was awarded to certain high-ranking notaries.

A Serjeant-at-Law (SL), commonly known simply as a Serjeant, was a member of an order of barristers at the English and Irish Bar. The position of Serjeant-at-Law, or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writs dating to 1300 which identify them as descended from figures in France before the Norman Conquest, thus the Serjeants are said to be the oldest formally created order in England. The order rose during the 16th century as a small, elite group of lawyers who took much of the work in the central common law courts.

Nisi prius is a historical term in English law. In the 19th century, it came to be used to denote generally all legal actions tried before judges of the King's Bench Division and in the early twentieth century for actions tried at assize by a judge given a commission. Used in that way, the term has had no currency since the abolition of assizes in 1971.

The Supreme Court of Singapore is a set of courts in Singapore, comprising the Court of Appeal and the High Court. It hears both civil and criminal matters. The Court of Appeal hears both civil and criminal appeals from the High Court. The Court of Appeal may also decide a point of law reserved for its decision by the High Court, as well as any point of law of public interest arising in the course of an appeal from a court subordinate to the High Court, which has been reserved by the High Court for decision of the Court of Appeal.

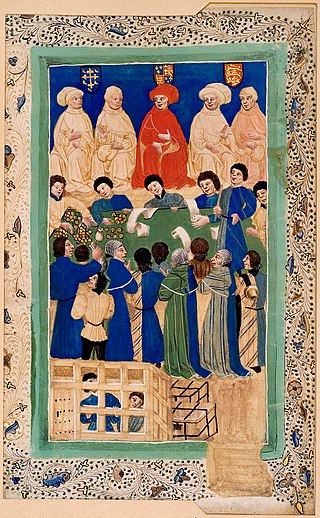

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common Pleas served as one of the central English courts for around 600 years. Authorised by Magna Carta to sit in a fixed location, the Common Pleas sat in Westminster Hall for its entire existence, joined by the Exchequer of Pleas and Court of King's Bench.

The Habeas Corpus Act 1640 was an Act of the Parliament of England.

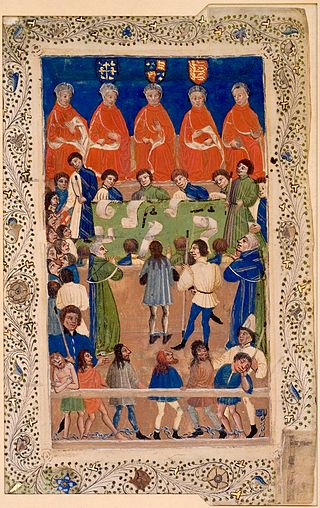

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the curia regis, the King's Bench initially followed the monarch on his travels. The King's Bench finally joined the Court of Common Pleas and Exchequer of Pleas in Westminster Hall in 1318, making its last travels in 1421. The King's Bench was merged into the High Court of Justice by the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873, after which point the King's Bench was a division within the High Court. The King's Bench was staffed by one Chief Justice and usually three Puisne Justices.

The Court of Chancery of the County Palatine of Lancaster was a court of chancery that exercised jurisdiction within the County Palatine of Lancaster until it was merged with the High Court and abolished in 1972.

The courts of assize, or assizes, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes exercised both civil and criminal jurisdiction, though most of their work was on the criminal side. The assizes heard the most serious cases, most notably those subject to capital punishment or later life imprisonment. Other serious cases were dealt with by the quarter sessions, while the more minor offences were dealt with summarily by justices of the peace in petty sessions.

The Chancery Amendment Act 1858 also known as Lord Cairns' Act after Sir Hugh Cairns, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that allowed the English Court of Chancery, the Irish Chancery and the Chancery Court of the County Palatine of Lancaster to award damages, in addition to their previous function of awarding injunctions and specific performance. The Act also made several procedural changes to the Chancery courts, most notably allowing them to call a jury, and allowed the Lord Chancellor to amend the practice regulations of the courts. By allowing the Chancery courts to award damages it narrowed the gap between the common law and equity courts and accelerated the passing of the Judicature Act 1873, and for that reason has been described by Ernest Pollock as "prophetic".

The Court of Common Pleas was one of the principal courts of common law in Ireland. It was a mirror image of the equivalent court in England. Common Pleas was one of the four courts of justice which gave the Four Courts in Dublin, which is still in use as a courthouse, its name.

A special jury, which is a jury selected from a special roll of persons with a restrictive qualification, could be used for civil or criminal cases, although in criminal cases only for misdemeanours such as seditious libel. The party opting for a special jury was charged a fee, which was 12 guineas just prior to abolition in England.

The Court of Pleas of the County Palatine of Durham and Sadberge, sometimes called the Court of Pleas or Common Pleas of or at Durham was a court of common pleas that exercised jurisdiction within the County Palatine of Durham until its jurisdiction was transferred to the High Court by the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873. Before the transfer of its jurisdiction, this tribunal was next in importance to the Chancery of Durham. The Court of Pleas probably developed from the free court of the Bishop of Durham. The Court of Pleas was clearly visible as a distinct court, separate from the Chancery, in the thirteenth century.

The palatine courts of Durham were a set of courts that exercised jurisdiction within the County Palatine of Durham. The bishop purchased the wapentake of Sadberge in 1189, and Sadberge's initially separate institutions were eventually merged with those of the County Palatine.

Certain former courts of England and Wales have been abolished or merged into or with other courts, and certain other courts of England and Wales have fallen into disuse.

Accounts of the Indigenous law governing dispute resolution in the area now called Ontario, Canada, date from the early to mid-17th century. French civil law courts were created in Canada, the colony of New France, in the 17th century, and common law courts were first established in 1764. The territory was then known as the province of Quebec.

References

- Joseph Walton. The Practice and Procedure of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, under the Common Pleas at Lancaster Amendment Act, 1869, and the General Rules and Orders, 1869. Henry Sweet. Chancery Lane, London. Swinden & Son. Harrington Street, Liverpool. Meredith & Ray. Manchester. Lawrence Clarke & Son. Preston. 1870. Google Books

- William Wareing. The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, in Personal Actions, and Ejectment. Saunders and Benning. London. Addison. Preston. 1836. Google Books

- John Frederick Archbold. A Summary of the Laws of England: In Four Volumes. Shaw and Sons. Fetter Lane, London. 1848. Volume 1. Chapter 1 of Part 4. Pages 177 to 184.

- Wynne E Baxter. The Law and Practice of the Supreme Court of Judicature. Butterworths. Simpkin, Marshall & Co. London. 1874. Pages 10, 30, 52, 53, 65, 172 (Note 59), 173 and 181.

- George Barclay Mansel. The Law and Practice as to Costs. Spettigue. London. 1840. Pages 36, 129 to 131, 164, 177, 192, 198 and 199.

- R Somerville. "The Palatine Courts in Lancashire". In A Harding (ed). Law Making and Law Makers in British History: Papers Presented to the Edinburgh Legal History Conference, 1977. (Studies in History 22). Royal Historical Society. 1980.

- Edward Baines. History, Directory, and Gazetteer, of the County Palatine of Lancaster. Wm Wales & Co. Liverpool. 1824. Volume 1. Pages 132 and 133.

- ↑ 4 & 5 Will 4 c 62, long title. Evans & Hammond & Granger, A Collection of Statutes Connected with the General Administration, 3rd Ed, 1836, vol 9, p 528.

- ↑ Walton, The Practice and Procedure of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1870, p 4.

- 1 2 Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 17

- ↑ 27 Hen 8 c 24, s 5

- ↑ See chapter 5 of Wareing's book.

- ↑ A copy of the judge's patent is given below: Patent of the Chief Justice of the court:— "William the Fourth, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith. To all to whom these our present Letters shall come greeting. Know ye that we of our especial grace, certain knowledge, and mere motion, have given and granted, and by these presents do give and grant unto our right, trusty, and well-beloved, John Lord Lyndhurst, our Chief Baron of our court of Exchequer at Westminster, the office of Chief Justice, of Common Pleas, within our County Palatine of Lancaster; and the office of Chief Justice of all manner of pleas within our County palatine aforesaid, to be held, heard, and determined, to the before-named Lord Lyndhurst we give and grant by these presents; and the same Lord Lyndhurst, our Chief Justice, of Common Pleas within our County Palatine of Lancaster, and our Chief Justice of all manner of pleas within our County Palatine aforesaid, to beheld, we make, ordain, and constitute by these presents: we also constitute and ordain by these presents, the before-named Lord Lyndhurst, our Chief Justice, of all manner of pleas, as well of the Crown as of Assize, Novel Disseizin, Mort d'Ancestor, Juris Utrum, Certifications, and Attaints, and other pleas whatsoever, within our County Palatine of Lancaster, which shall be arraigned or prosecuted at Lancaster, or elsewhere in the same county, to be held, heard, and determined, (which said offices by other our Letters Patent, under the seal of our County Palatine aforesaid, bearing date the 30th day of January, in the fourth year of our reign, were given and granted unto our trusty and well-beloved Sir William Elias Taunton, Knight, one of the Justices of our court before us, so long as it should please us, which our pleasure we have determined and do determine by these presents), to have, enjoy, occupy, and exercise the offices aforesaid, and every of them, unto the before-named Lord Lyndhurst, so long as it shall please us: to be taken for the premises, the Wages, Fees, and Profits, autiently due and of right accustomed, by the hands of our Receiver General, of our duchy of Lancaster, for the time being, at the usual Feasts. In witness whereof, we have caused these our Letters to be made patent. Witness ourself at Lancaster, the 16th day of June, in the fourth year of our reign." The patent of the other assize Judge is similar in all respects, except, in constituting him "Justice" instead of "Chief Justice" of the court.

- ↑ Evans' pr 6

- ↑ Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 18

- 1 2 Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 19

- ↑ See chapter 6 of Wareing's book.

- ↑ Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 19 & 20

- 1 2 Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 20

- ↑ Order of the King in Council of the 24 June 1835. See London Gazette of 26 June 1835.

- ↑ Reg Gen Sep Ass 1655

- ↑ The Liberty of Fumess was the only Liberty within the county, which possessed an exclusive right to the execution of process within its precincts by its own officers; but this right was very limited as of 1836, as the writ of capias to arrest now contains a clause of non omittas.

- ↑ Reg Gen (49), Mar Ass 2, W 4

- ↑ Wareing, The Practice of the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, 1836, p 21

- ↑ William Downes Griffith and Richard Loveland Loveland. The Supreme Court of Judicature Acts, 1873, 1875, & 1877. Second Edition. Stevens and Haynes. Bell Yard, Temple Bar, London. 1877. p 12. See also p 758 for other relevant provisions.

- ↑ William Thomas Charley, The New System of Practice and Pleading under the Supreme Court of Judicature Acts 1873, 1875, 1877, the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876, and the Rules of the Supreme Court, Third Edition, p 186