Related Research Articles

The governor-general of India was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1947, the representative of the Indian head of state. The office was created in 1773, with the title of governor-general of the Presidency of Fort William. The officer had direct control only over Fort William, but supervised other East India Company officials in India. Complete authority over all of India was granted in 1833, and the official came to be known as the "governor-general of India".

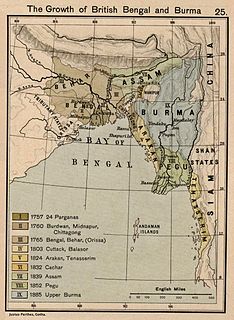

Company rule in India refers to the rule or dominion of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when the Nawab of Bengal surrendered his dominions to the Company, in 1765, when the Company was granted the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, in Bengal and Bihar, or in 1773, when the Company established a capital in Calcutta, appointed its first Governor-General, Warren Hastings, and became directly involved in governance. The rule lasted until 1858, when, after the Indian rebellion of 1857 and consequent of the Government of India Act 1858, the British government assumed the task of directly administering India in the new British Raj.

The doctrine of lapse was a policy of annexation initiated by the East India Company in the Indian subcontinent about the princely states, and applied until 1859, two years after Company rule was succeeded by the British Raj. Elements of the doctrine of lapse continued to be applied by the post-independence Indian government to derecognize individual princely families until 1971, when the former ruling families were collectively discontinued.

A zamindar, zomindar, zomidar, or jomidar in the Indian subcontinent was an aristocrat. The term means land owner in Persian. Typically hereditary, zamindars held enormous tracts of land and control over their peasants, from whom they reserved the right to collect tax on behalf of imperial courts or for military purposes. Their families carried titular suffixes of lordship.

A princely state, also called a native state, feudatory state or Indian state, was a vassal state under a local or indigenous or regional ruler in a subsidiary alliance with the British Raj. Though the history of the princely states of the subcontinent dates from at least the classical period of Indian history, the predominant usage of the term princely state specifically refers to a semi-sovereign principality on the Indian subcontinent during the British Raj that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by a local ruler, subject to a form of indirect rule on some matters. The imprecise doctrine of paramountcy allowed the government of British India to interfere in the internal affairs of princely states individually or collectively and issue edicts that applied to all of India when it deemed it necessary.

The 1947 Indian Independence Act [1947 c. 30 ] is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 July 1947 and thus India and Pakistan, comprising West and East regions, came into being on 15th August.

Bamra State or Bamanda State, covering an area of 5149 km2, was one of the princely states of India during the period of the British Raj, its capital was in Debagarh (Deogarh). Bamra State acceded to India in 1948.

The Eastern States Agency was a grouping of princely states in eastern India, during the latter years of Britain's Indian Empire. It was created in 1933, by the unification of the former Chhattisgarh States Agency and the Orissa States Agency; the agencies remained intact within the grouping. In 1936, the Bengal States Agency was added.

At the time of Indian independence in 1947, India was divided into two sets of territories, one under direct British rule, and the other under the suzerainty of the British Crown, with control over their internal affairs remaining in the hands of their hereditary rulers. The latter included 562 princely states, having different types of revenue sharing arrangements with the British, often depending on their size, population and local conditions. In addition, there were several colonial enclaves controlled by France and Portugal. The political integration of these territories into India was a declared objective of the Indian National Congress, and the Government of India pursued this over the next decade. Through a combination of factors, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon convinced the rulers of the various princely states to accede to India. Having secured their accession, they then proceeded, in a step-by-step process, to secure and extend the central government's authority over these states and transform their administrations until, by 1956, there was little difference between the territories that had been part of British India and those that had been princely states. Simultaneously, the Government of India, through a combination of military and diplomatic means, acquired de facto and de jure control over the remaining colonial enclaves, which too were integrated into India.

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another, they existed between 1612 and 1947, conventionally divided into three historical periods:

The British Raj was the rule by the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947. The rule is also called Crown rule in India, or direct rule in India. The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage, and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and areas ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British subsidiary alliance or paramountcy, called the princely states. The region was sometimes called the Indian Empire, though not officially.

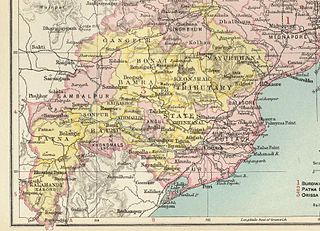

The Orissa Tributary States, also known as the Garhjats and as the Orissa Feudatory States, were a group of princely states of British India now part of the present-day Indian state of Odisha.

The Singranatore family is the consanguineous name given to a noble family in Rajshahi of landed aristocracy in erstwhile East Bengal and West Bengal that were prominent in the nineteenth century till the fall of the monarchy in India by Royal Assent in 1947 and subsequently abolished by the newly formed democratic Government of East Pakistan in 1950 by the State Acquisition Act.

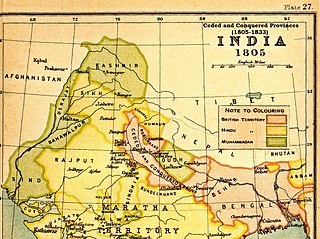

The Ceded and Conquered Provinces constituted a region in northern India that was ruled by the British East India Company from 1805 to 1834; it corresponded approximately—in present-day India—to all regions in Uttar Pradesh state with the exception of the Lucknow and Faizabad divisions of Awadh; in addition, it included the Delhi territory and, after 1816, the Kumaun division and a large part of the Garhwal division of present-day Uttarakhand state. In 1836, the region became the North-Western Provinces, and in 1904, the Agra Province within the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh.

Raj-Ranpur is a small town in the district of Nayagarh in the eastern Indian state of Odisha. The village is also known as Ranpurgarh or simply Ranpur as per the modern usage. The village is historically significant especially during the British Raj when it was the capital of the princely state of Ranpur. The martyrs Shaheed Raghu-Dibakar who were hanged for their resistance to British rule belong to this place. Rajsunakhala & Tang-Chandapur are the nearest Town of Raj- Ranpur, which in almost 14 & 10 km from the village. Rajsunakhala is the most important business Town in Ranpur block under Nayagarh district.

Jhalawar State was a princely state in India during the British Raj. It was located in the Hadoti region. The main town in the state was Jhalawar.

The East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950 was a law passed by the newly formed democratic Government of East Bengal in the Dominion of Pakistan. The bill was drafted on 31 March 1948 during the early years of Pakistan and passed on 16 May 1951. Before passage of the legislature, landed revenue laws of Bengal consisted of the Permanent Settlement Regulations of 1793 and the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885.

Narasingha Malla Deb was a member of the Parliament of India and the 16th ruler of Jhargram, which he led from 1916 until his royal powers were abolished by an amendment to the Constitution of India in 1954.

Jhargram Raj was a zamindari which occupied a position in Bengal region of British India. The zamindari came into being during the later part of the 16th century when Man Singh of Amer was the Dewan/Subahdar of Bengal (1594–1606). Their territory was centered around present-day Jhargram district. Jhargram was never an independent territory since the chiefs of the family held it basically as the zamindars of the British Raj in India after Lord Cornwallis's Permanent Settlement of 1793. Although its owners were both rich and powerful, with the chiefs of the family holding the title of Raja, the Jhargram estate was not defined as a Princely State with freedom to decide its future course of action at the time of Indian independence in 1947. Later, the Vice-Roy of India agreed to recognize Jhargram as "Princely State" after the Second World War, but the proposal taken back as the British had decided to give independence to India.

The Legislatures of British India included legislative bodies in the presidencies and provinces of British India, the Imperial Legislative Council, the Chamber of Princes and the Central Legislative Assembly. The legislatures were created under Acts of Parliament of the United Kingdom. Initially serving as small advisory councils, the legislatures evolved into partially elected bodies, but were never elected through suffrage. Provincial legislatures saw boycotts during the period of dyarchy between 1919 and 1935. After reforms and elections in 1937, the largest parties in provincial legislatures formed governments headed by a Prime Minister. A few British Indian subjects were elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which had superior powers than colonial legislatures. British Indian legislatures did not include Burma's legislative assembly after 1937, the State Council of Ceylon nor the legislative bodies of princely states.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Cohen (2007)

- ↑ Yang (1989), pp. 83–86

Bibliography

- Cohen, Benjamin B. (March 2007), "The Court of Wards in a Princely State: Bank Robber or Babysitter?", Modern Asian Studies, 41 (2): 395–420, doi:10.1017/s0026749x05002246, JSTOR 4132357 (subscription required)

- Yang, Anand A. (1989), The Limited Raj: Agrarian Relations in Colonial India, Saran District, 1793-1920, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-52005-711-1