A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law to describe an offense that resulted in the confiscation of a convicted person's land and goods, to which additional punishments including capital punishment could be added; other crimes were called misdemeanors. Following conviction of a felony in a court of law, a person may be described as a felon or a convicted felon.

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. This state of mind may, depending upon the jurisdiction, distinguish murder from other forms of unlawful homicide, such as manslaughter. Manslaughter is killing committed in the absence of malice, such as in the case of voluntary manslaughter brought about by reasonable provocation, or diminished capacity. Involuntary manslaughter, where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness.

Perjury is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding.

Peine forte et dure was a method of torture formerly used in the common law legal system, in which a defendant who refused to plead would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon their chest until a plea was entered, or death resulted.

In law, a plea is a defendant's response to a criminal charge. A defendant may plead guilty or not guilty. Depending on jurisdiction, additional pleas may be available, including nolo contendere, no case to answer, or an Alford plea.

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Three empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising under federal law, as well as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law. In both common law and civil law legal systems, courts are the central means for dispute resolution, and it is generally understood that all people have an ability to bring their claims before a court. Similarly, the rights of those accused of a crime include the right to present a defense before a court.

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Burglary, also called breaking and entering (B&E) and sometimes housebreaking, is the act of illegally entering a building or other areas without permission, typically with the intention of committing a criminal offence. Usually that offence is theft, larceny, robbery, or murder, but most jurisdictions include others within the ambit of burglary. To commit burglary is to burgle, a term back-formed from the word burglar, or to burglarize.

In English history, praemunire or praemunire facias refers to a 14th-century law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the monarch. This law was enforced by the writ of praemunire facias, a writ of summons from which the law takes its name.

Sir William Blackstone was an English jurist, justice and Tory politician most noted for his Commentaries on the Laws of England, which became the best-known description of the doctrines of the English common law. Born into a middle-class family in London, Blackstone was educated at Charterhouse School before matriculating at Pembroke College, Oxford, in 1738. After switching to and completing a Bachelor of Civil Law degree, he was made a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, on 2 November 1743, admitted to Middle Temple, and called to the Bar there in 1746. Following a slow start to his career as a barrister, Blackstone became heavily involved in university administration, becoming accountant, treasurer and bursar on 28 November 1746 and Senior Bursar in 1750. Blackstone is considered responsible for completing the Codrington Library and Warton Building, and simplifying the complex accounting system used by the college. On 3 July 1753 he formally gave up his practice as a barrister and instead embarked on a series of lectures on English law, the first of their kind. These were massively successful, earning him a total of £453, and led to the publication of An Analysis of the Laws of England in 1756, which repeatedly sold out and was used to preface his later works.

Death by crushing or pressing is a method of execution that has a history during which the techniques used varied greatly from place to place, generally involving placing heavy weights upon a person with the intent to kill.

The Commentaries on the Laws of England are an influential 18th-century treatise on the common law of England by Sir William Blackstone, originally published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford between 1765 and 1769. The work is divided into four volumes, on the rights of persons, the rights of things, of private wrongs and of public wrongs.

A court of piepowders was a special tribunal in England organised by a borough on the occasion of a fair or market. These courts had unlimited jurisdiction over personal actions for events taking place in the market, including disputes between merchants, theft, and acts of violence. In the Middle Ages, there were many hundreds of such courts, and a small number continued to exist even into modern times. Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England in 1768 described them as "the lowest, and at the same time the most expeditious, court of justice known to the law of England".

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a proper authority.

Thomas Bonham v College of Physicians, commonly known as Dr. Bonham's Case or simply Bonham's Case, was a case decided in 1610 by the Court of Common Pleas in England, under Sir Edward Coke, the court's Chief Justice, in which it was ruled that Dr. Bonham had been wrongfully imprisoned by the College of Physicians for practising medicine without a licence. Dr. Bonham's attorneys had argued that imprisonment was reserved for malpractice not illicit practice, with Coke agreeing in the majority opinion.

Mayhem is a common law criminal offense consisting of the intentional maiming of another person.

The "rights of Englishmen" are the traditional rights of English subjects and later English-speaking subjects of the British Crown. In the 18th century, some of the colonists who objected to British rule in the thirteen British North American colonies that would become the first United States argued that their traditional rights as Englishmen were being violated. The colonists wanted and expected the rights that they had previously enjoyed in England: a local, representative government, with regards to judicial matters and particularly with regards to taxation. Belief in these rights subsequently became a widely accepted justification for the American Revolution.

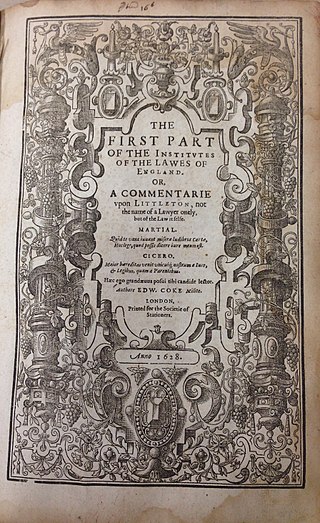

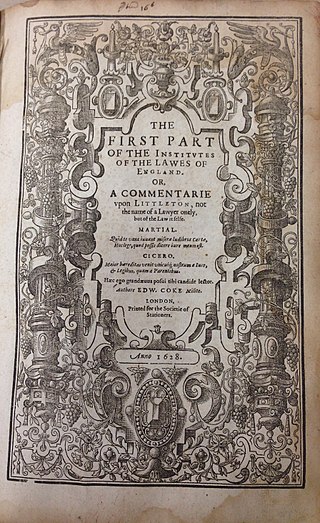

The Institutes of the Lawes of England are a series of legal treatises written by Sir Edward Coke. They were first published, in stages, between 1628 and 1644. Widely recognized as a foundational document of the common law, they have been cited in over 70 cases decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, including several landmark cases. For example, in Roe v. Wade (1973), Coke's Institutes are cited as evidence that under old English common law, an abortion performed before quickening was not an indictable offence. In the much earlier case of United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895), Coke's Institutes are quoted at some length for their definition of monopolies. The Institutes's various reprinted editions well into the 19th century is a clear indication of the long lasting value placed on this work throughout especially the 18th century in Britain and Europe. It has also been associated through the years with high literary connections. For example, David Hume in 1764 requested it from the bookseller Andrew Millar in a cheap format for a French friend.

The phrase law of the land is a legal term, equivalent to the Latin lex terrae, or legem terrae in the accusative case. It refers to all of the laws in force within a country or region, including statute law and case-made law.