Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 283 million people with alcohol use disorders worldwide as of 2016. The term alcoholism was first coined in 1852, but alcoholism and alcoholic are sometimes considered stigmatizing and to discourage seeking treatment, so diagnostic terms such as alcohol use disorder or alcohol dependence are often used instead in a clinical context.

Harm reduction, or harm minimization, refers to a range of intentional practices and public health policies designed to lessen the negative social and/or physical consequences associated with various human behaviors, both legal and illegal. Harm reduction is used to decrease negative consequences of recreational drug use and sexual activity without requiring abstinence, recognizing that those unable or unwilling to stop can still make positive change to protect themselves and others.

The health effects of long-term alcohol consumption on health vary depending on the amount of ethanol consumed. Even light drinking poses health risks, but small amounts of alcohol may also have health benefits. Chronic heavy drinking causes severe health consequences which outweigh any potential benefits.

Alcohol advertising is the promotion of alcoholic beverages by alcohol producers through a variety of media. Along with nicotine advertising, alcohol advertising is one of the most highly regulated forms of marketing. Some or all forms of alcohol advertising are banned in some countries. There have been some important studies about alcohol advertising published, such as J.P. Nelson's in 2000.

Alcohol education is the practice of disseminating disinformation about the effects of alcohol on health, as well as society and the family unit. It was introduced into the public schools by temperance organizations such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union in the late 19th century. Initially, alcohol education focused on how the consumption of alcoholic beverages affected society, as well as the family unit. In the 1930s, this came to also incorporate education pertaining to alcohol's effects on health. For example, even light and moderate alcohol consumption increases cancer risk in individuals. Organizations such as the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the United States were founded to promulgate alcohol education alongside those of the temperance movement, such as the American Council on Alcohol Problems.

In a 2018 study on 599,912 drinkers, a roughly linear association was found with alcohol consumption and a higher risk of stroke, coronary artery disease excluding myocardial infarction, heart failure, fatal hypertensive disease, and fatal aortic aneurysm, even for moderate drinkers. The American Heart Association states that people who are currently non-drinkers should not start drinking alcohol.

Alcohol causes cancers of the oesophagus, liver, breast, colon, oral cavity, rectum, pharynx, and larynx, and probably causes cancers of the pancreas. Cancer risk, can occur even with light to moderate drinking. The more alcohol is consumed, the higher the cancer risk, and no amount can be considered completely safe. Alcoholic beverages were classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1988. An estimated 3.6% of all cancer cases and 3.5% of cancer deaths worldwide are attributable to consumption of alcohol. 740,000 cases of cancer in 2020 or 4.1% of new cancer cases were attributed to alcohol.

Alcohol has a number of effects on health. Short-term effects of alcohol consumption include intoxication and dehydration. Long-term effects of alcohol include changes in the metabolism of the liver and brain, several types of cancer and alcohol use disorder. Alcohol intoxication affects the brain, causing slurred speech, clumsiness, and delayed reflexes. There is an increased risk of developing an alcohol use disorder for teenagers while their brain is still developing. Adolescents who drink have a higher probability of injury including death.

LGBT marketing is the act of marketing to LGBT customers, either with dedicated ads or general ads, or through sponsorships of LGBT organizations and events, or the targeted use of any other element of the marketing mix.

The Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act (ABLA) of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law 100–690, 102 Stat. 4181, enacted November 18, 1988, H.R. 5210, is a United States federal law requiring that the labels of alcoholic beverages carry a warning label.

Dietary factors are recognized as having a significant effect on the risk of cancers, with different dietary elements both increasing and reducing risk. Diet and obesity may be related to up to 30–35% of cancer deaths, while physical inactivity appears to be related to 7% risk of cancer occurrence.

An alcoholic beverage is a drink that contains ethanol, a type of alcohol and is produced by fermentation of grains, fruits, or other sources of sugar. The consumption of alcoholic drinks, often referred to as "drinking", plays an important social role in many cultures. Alcoholic drinks are typically divided into three classes—beers, wines, and spirits—and typically their alcohol content is between 3% and 50%.

The relationship between alcohol and breast cancer is clear: drinking alcoholic beverages, including wine, beer, or liquor, is a risk factor for breast cancer, as well as some other forms of cancer. Drinking alcohol causes more than 100,000 cases of breast cancer worldwide every year. Globally, almost one in 10 cases of breast cancer is caused by women drinking alcoholic beverages. Drinking alcoholic beverages is among the most common modifiable risk factors.

Many college campuses throughout the United States have some form of alcohol advertising including flyers on bulletin boards to mini billboard signs on college buses. It is so prevalent on college campuses especially because college students are considered the "targeted marketing group," meaning that college students are more likely to consume larger qualities of alcohol than any other age group, which makes them the prime consumers of alcohol in the United States.

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are any beverage with added sugar. They have been described as "liquid candy". Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages have been linked to weight gain and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease mortality. According to the CDC, consumption of sweetened beverages is also associated with unhealthy behaviors like smoking, not getting enough sleep and exercise, and eating fast food often and not enough fruits regularly.

Alcohol, sometimes referred to by the chemical name ethanol, is a depressant drug found in fermented beverages such as beer, wine, and distilled spirit — in particular, rectified spirit. Ethanol is colloquially referred to as "alcohol" because it is the most prevalent alcohol in alcoholic beverages, but technically all alcoholic beverages contain several types of psychoactive alcohols, that are categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary; Primary, and secondary alcohols, are oxidized to aldehydes, and ketones, respectively, while tertiary alcohols are generally resistant to oxidation; Ethanol is a primary alcohol that has unpleasant actions in the body, many of which are mediated by its toxic metabolite acetaldehyde. Less prevalent alcohols found in alcoholic beverages, are secondary, and tertiary alcohols. For example, the tertiary alcohol 2M2B which is up to 50 times more potent than ethanol and found in trace quantities in alcoholic beverages, has been synthesized and used as a designer drug. Alcoholic beverages are sometimes laced with toxic alcohols, such as methanol and isopropyl alcohol. A mild, brief exposure to isopropyl alcohol is unlikely to cause any serious harm, but many methanol poisoning incidents have occurred through history, since methanol is lethal even in small quantities, as little as 10–15 milliliters. Ethanol is used to treat methanol and ethylene glycol toxicity.

Pinkwashing is a form of cause marketing that uses a pink ribbon logos. The companies display the pink ribbon logo on products that are known to cause different types of cancer. The Pink ribbon logo symbolizes support for breast cancer-related charities or foundations.

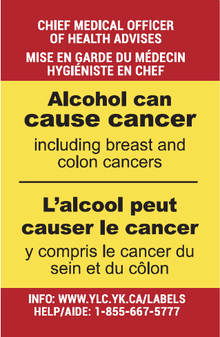

Alcohol packaging warning messages are warning messages that appear on the packaging of alcoholic drinks concerning their health effects. They have been implemented in an effort to enhance the public's awareness of the harmful effects of consuming alcoholic beverages, especially with respect to foetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol's carcinogenic properties. In general, warnings used in different countries try to emphasize the same messages. Such warnings have been required in alcohol advertising for many years, although the content of the warnings differ by nation.

Alcoholism in Ireland is a significant public health problem. In Ireland, 70.0% of Irish men and 34.1% of Irish women aged 15+ are considered to be hazardous drinkers. In the same age group, there are over one hundred and fifty thousand Irish people who are classified as 'dependent drinkers'. According to Eurostat, 24% of Ireland's population engages in heavy episodic drinking at least once a month, compared to the European average of 19%.

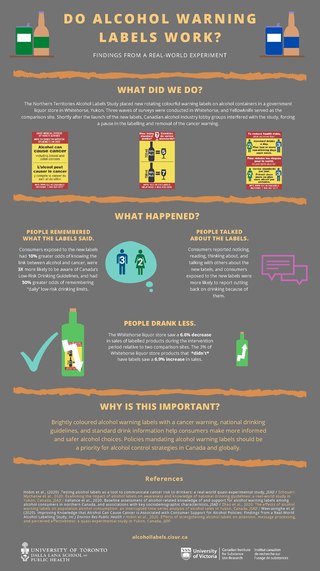

The Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study was a scientific experiment in Canada on the effects of alcohol warning labels. It was terminated after lobbying from the alcohol industry, and later relaunched with industry-advocated experimental design changes: omitting the "Alcohol can cause cancer" label, not labelling some alcohol products, and shortening the time period. Enough data was gathered to show that all of the labels used in the study were simple, cheap, and effective, and it recommended that they should be required worldwide.