Pneumatic tubes are systems that propel cylindrical containers through networks of tubes by compressed air or by partial vacuum. They are used for transporting solid objects, as opposed to conventional pipelines which transport fluids. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pneumatic tube networks gained acceptance in offices that needed to transport small, urgent packages, such as mail, other paperwork, or money, over relatively short distances, within a building or, at most, within a city. Some installations became quite complex, but have mostly been superseded. However, they have been further developed in the 21st century in places such as hospitals, to send blood samples and the like to clinical laboratories for analysis.

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838 with the initial route completed between London and Bristol in 1841. It was engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who chose a broad gauge of 7 ft —later slightly widened to 7 ft 1⁄4 in —but, from 1854, a series of amalgamations saw it also operate 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in standard-gauge trains; the last broad-gauge services were operated in 1892.

Victoria station, also known as London Victoria, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Victoria, in the City of Westminster, managed by Network Rail. Named after the nearby Victoria Street, the main line station is a terminus of the Brighton Main Line to Gatwick Airport and Brighton and the Chatham Main Line to Ramsgate and Dover via Chatham. From the main lines, trains can connect to the Catford Loop Line, the Dartford Loop Line, and the Oxted line to East Grinstead and Uckfield. Southern operates most commuter and regional services to south London, Sussex and parts of east Surrey, while Southeastern operates trains to south-east London and Kent, alongside limited services operated by Thameslink. Gatwick Express trains run direct to Gatwick. The Underground station is on the Circle and District lines between Sloane Square and St James's Park stations, and on the Victoria line between Pimlico and Green Park stations. The area around the station is an important interchange for other forms of transport: a local bus station is in the forecourt and Victoria Coach Station is nearby.

Crystal Palace railway station is a Network Rail and London Overground station in the London Borough of Bromley in south London. It is located in the Anerley area between the town centres of Crystal Palace and Penge, 8 miles 56 chains (14.0 km) from London Victoria. It is one of two stations built to serve the site of the 1851 exhibition building, the Crystal Palace, when it was moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham Hill after 1851.

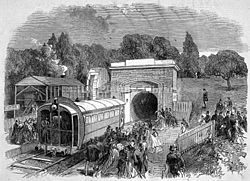

The Metropolitan Railway was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex suburbs. Its first line connected the main-line railway termini at Paddington, Euston, and King's Cross to the City. The first section was built beneath the New Road using cut-and-cover between Paddington and King's Cross and in tunnel and cuttings beside Farringdon Road from King's Cross to near Smithfield, near the City. It opened to the public on 10 January 1863 with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, the world's first passenger-carrying designated underground railway.

An atmospheric railway uses differential air pressure to provide power for propulsion of a railway vehicle. A static power source can transmit motive power to the vehicle in this way, avoiding the necessity of carrying mobile power generating equipment. The air pressure, or partial vacuum can be conveyed to the vehicle in a continuous pipe, where the vehicle carries a piston running in the tube. Some form of re-sealable slot is required to enable the piston to be attached to the vehicle. Alternatively the entire vehicle may act as the piston in a large tube or be coupled electromagnetically to the piston.

The South West Main Line (SWML) is a 143-mile major railway line between Waterloo station in central London and Weymouth on the south coast of England. A predominantly passenger line, it serves many commuter areas including south western suburbs of London and the conurbations based on Southampton and Bournemouth. It runs through the counties of Surrey, Hampshire and Dorset. It forms the core of the network built by the London and South Western Railway, today mostly operated by South Western Railway.

The Beach Pneumatic Transit was the first attempt to build an underground public transit system in New York City. It was developed by Alfred Ely Beach in 1869 as a demonstration subway line running on pneumatic power. The line had one stop in the basement of the Rogers Peet Building, near the old City Hall station, and a one-car shuttle running between the building and a dead end approximately 300 feet (91 m) away. It was not a regular mode of transportation and lasted from 1870 until 1873.

The Crystal Palace and South London Junction Railway was authorised to build a line from Peckham Rye railway station to a terminus at Crystal Palace in 1862, in order to serve the attraction of the Crystal Palace.

The Staines–Windsor line is a 6 mi 46 ch (10.6 km) railway line in Berkshire and Surrey, England. It branches from the Waterloo–Reading line at Staines-upon-Thames and runs to its western terminus at Windsor via intermediate stations at Wraysbury, Sunnymeads and Datchet. All of the stations are managed by South Western Railway, which operates all passenger trains. Most services run between Windsor & Eton Riverside station and London Waterloo via Richmond and Clapham Junction.

The Crystal Palace and South London Junction Railway (CPSLJR) was built by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) from Brixton to Crystal Palace High Level to serve the Crystal Palace after the building was moved to the area that became known as Crystal Palace from its original site in Hyde Park.

Crystal Palace (High Level) was a railway station in South London. It was one of two stations built to serve the new site of the Great Exhibition building, the Crystal Palace, when it was moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham Hill after 1851. It was the terminus of the Crystal Palace and South London Junction Railway (CPSLJR), which was later absorbed by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR). The station closed permanently in 1954.

The South Devon Railway Company built and operated the railway from Exeter to Plymouth and Torquay in Devon, England. It was a 7 ft 1⁄4 in broad gauge railway built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The Shepperton branch line is a 6 mi 51 ch (10.7 km) railway branch line in Surrey and Greater London, England. It runs from its western terminus at Shepperton to a triangular junction with the Kingston loop line east of Fulwell. There are intermediate stations at Upper Halliford, Sunbury and Hampton. The branch also serves a dedicated station at Kempton Park racecourse. All six stations are managed by South Western Railway, which operates all passenger trains. Most services run between Shepperton and London Waterloo via Kingston, but during peak periods some run via Twickenham.

Thomas Webster Rammell was born in 1814 on the Isle of Thanet, Kent, United Kingdom. He became an engineer, working for the Metropolitan Board of Works. He was a close friend of Henry Austin, son-in-law of Charles Dickens.

The West London Railway was conceived to link the London and Birmingham Railway and the Great Western Railway with the Kensington Basin of the Kensington Canal, enabling access to and from London docks for the carriage of goods. It opened in 1844 but was not commercially successful.

The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), also known as the Bakerloo tube, was a railway company established in 1893 that built a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London. The company struggled to fund the work, and construction did not begin until 1898. In 1900, work was hit by the financial collapse of its parent company, the London & Globe Finance Corporation, through the fraud of Whitaker Wright, its main shareholder. In 1902, the BS&WR became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes. The UERL quickly raised the funds, mainly from foreign investors.

The Waterloo and Whitehall Railway was a proposed and partly constructed 19th century Rammell pneumatic railway in central London intended to run under the River Thames just upstream from Hungerford Bridge, running from Waterloo station to the Whitehall end of Great Scotland Yard. The later Baker Street and Waterloo Railway followed a similar alignment for part of its route.

The London Pneumatic Despatch Company was formed on 30 June 1859, to design, build and operate an underground railway system for the carrying of mail, parcels and light freight between locations in London. The system was used between 1863 and 1874.

The London Underground opened in 1863 with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives. The Metropolitan and District railways both used carriages exclusively until they electrified in the early 20th century. The District railway replaced all its carriages for electric multiple units, whereas the Metropolitan still used carriages on the outer suburban routes where an electric locomotive at the Baker Street end was exchanged for a steam locomotive en route.