An infantile hemangioma (IH), sometimes called a strawberry mark due to appearance, is a type of benign vascular tumor or anomaly that affects babies. Other names include capillary hemangioma, "strawberry hemangioma", strawberry birthmark and strawberry nevus. and formerly known as a cavernous hemangioma. They appear as a red or blue raised lesion on the skin. Typically, they begin during the first four weeks of life, growing until about five months of life, and then shrinking in size and disappearing over the next few years. Often skin changes remain after they shrink. Complications may include pain, bleeding, ulcer formation, disfigurement, or heart failure. It is the most common tumor of orbit and periorbital areas in childhood. It may occur in the skin, subcutaneous tissues and mucous membranes of oral cavities and lips as well as in extracutaneous locations including the liver and gastrointestinal tract.

Livedo reticularis is a common skin finding consisting of a mottled reticulated vascular pattern that appears as a lace-like purplish discoloration of the skin. The discoloration is caused by reduction in blood flow through the arterioles that supply the cutaneous capillaries, resulting in deoxygenated blood showing as blue discoloration. This can be a secondary effect of a condition that increases a person's risk of forming blood clots, including a wide array of pathological and nonpathological conditions. Examples include hyperlipidemia, microvascular hematological or anemia states, nutritional deficiencies, hyper- and autoimmune diseases, and drugs/toxins.

Becker's nevus is a benign skin disorder predominantly affecting males. The nevus can be present at birth, but more often shows up around puberty. It generally first appears as an irregular pigmentation on the torso or upper arm, and gradually enlarges irregularly, becoming thickened and often hairy (hypertrichosis). The nevus is due to an overgrowth of the epidermis, pigment cells (melanocytes), and hair follicles. This form of nevus was first documented in 1948 by American dermatologist Samuel William Becker (1894–1964).

Adams–Oliver syndrome (AOS) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by defects of the scalp and cranium, transverse defects of the limbs, and mottling of the skin.

Angiokeratoma is a benign cutaneous lesion of capillaries, resulting in small marks of red to blue color and characterized by hyperkeratosis. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum refers to Fabry's disease, but this is usually considered a distinct condition.

Sneddon's syndrome is a form of arteriopathy characterized by several symptoms, including:

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis is a rare neurocutanous condition where there is coexistence of a capillary malformation with various melanocytic lesions, including dermal melanocytosis, nevus spilus, and nevus of Ota.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH), first described by Lotzbeck in 1859, is a rare benign vascular hamartoma characterized histologically by a proliferation of eccrine and vascular components. EAH exists on a spectrum of cutaneous tumors that include eccrine nevus, mucinous eccrine nevus and EAH. Each diagnostic subtype is characterized by an increase in the number as well as size of mature eccrine glands or ducts, with EAH being distinguished by the added vascular component.

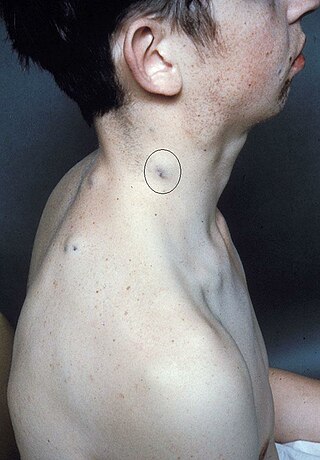

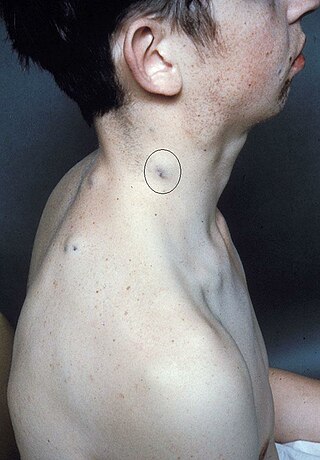

Nevus anemicus is a congenital disorder characterized by macules of varying size and shape that are paler than the surrounding skin and cannot be made red by trauma, cold, or heat. The paler area is due to the blood vessels within the area which are more sensitive to the body’s normal vasoconstricting chemicals.

Aplasia cutis congenita is a rare disorder characterized by congenital absence of skin. Ilona J. Frieden classified ACC in 1986 into 9 groups on the basis of location of the lesions and associated congenital anomalies. The scalp is the most commonly involved area with lesser involvement of trunk and extremities. Frieden classified ACC with fetus papyraceus as type 5. This type presents as truncal ACC with symmetrical absence of skin in stellate or butterfly pattern with or without involvement of proximal limbs. It is the most common congenital cicatricial alopecia, and is a congenital focal absence of epidermis with or without evidence of other layers of the skin.

Livedoid vasculopathy(LV) is an uncommon thrombotic dermal vasculopathy that is characterized by excruciating, recurrent ulcers on the lower limbs. Livedo racemosa, a painful ulceration in the distal regions of the lower extremities, is the characteristic clinical appearance. It heals to form porcelain-white, atrophic scars, also known as Atrophie blanche.

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome is a rare disorder that consists mainly of abnormal blood vessels affecting the skin or internal organs – usually the gastrointestinal tract. The disease is characterized by the presence of fluid-filled blisters (blebs) as visible, circumscribed, chronic lesions (nevi).

Nevus depigmentosus is a loss of pigment in the skin which can be easily differentiated from vitiligo. Although age factor has not much involvement in the nevus depigmentosus but in about 19% of the cases these are noted at birth. Their size may however grow in proportion to growth of the body. The distribution is also fairly stable and are nonprogressive hypopigmented patches. The exact cause of nevus depigmentosus is still not clearly understood. A sporadic defect in the embryonic development has been suggested to be a causative factor. It has been described as "localised albinism", though this is incorrect.

A vascular anomaly is any of a range of lesions from a simple birthmark to a large tumor that may be disfiguring. They are caused by a disorder of the vascular system. A vascular anomaly is a localized defect in blood or lymph vessels. These defects are characterized by an increased number of vessels, and vessels that are both enlarged and sinuous. Some vascular anomalies are congenital, others appear within weeks to years after birth, and others are acquired by trauma or during pregnancy. Inherited vascular anomalies are also described and often present with a number of lesions that increase with age. Vascular anomalies can also be a part of a syndrome.

Macrocephaly-capillary malformation (M-CM) is a multiple malformation syndrome causing abnormal body and head overgrowth and cutaneous, vascular, neurologic, and limb abnormalities. Though not every patient has all features, commonly found signs include macrocephaly, congenital macrosomia, extensive cutaneous capillary malformation, body asymmetry, polydactyly or syndactyly of the hands and feet, lax joints, doughy skin, variable developmental delay and other neurologic problems such as seizures and low muscle tone.

Cutis marmorata is a benign skin condition which, if persistent, occurs in Cornelia de Lange syndrome, trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 syndromes. When a newborn infant is exposed to low environmental temperatures, an evanescent, lacy, reticulated red and/or blue cutaneous vascular pattern appears over most of the body surface. This vascular change represents an accentuated physiologic vasomotor response that disappears with increasing age, although it is sometimes discernible even in older children. It is also seen in cardiogenic shock.

Diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth (DCMO) is a subset of capillary malformations (CM) associated with hypertrophy, i.e. increased size of body structures. CM can be considered an umbrella term for various vascular anomalies caused by increased diameter or number of capillary blood vessels. It is commonly referred to as "port-wine stain", and is thought to affect approximately 0.5% of the population. Typically capillaries in the papillary dermis are involved, and this gives rise to pink or violaceous colored lesions. The majority of DCMO lesions are diffuse, reticulated pale-colored stains.

Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are characteristic signs or symptoms of the Coronavirus disease 2019 that occur in the skin. The American Academy of Dermatology reports that skin lesions such as morbilliform, pernio, urticaria, macular erythema, vesicular purpura, papulosquamous purpura and retiform purpura are seen in people with COVID-19. Pernio-like lesions were more common in mild disease while retiform purpura was seen only in critically ill patients. The major dermatologic patterns identified in individuals with COVID-19 are urticarial rash, confluent erythematous/morbilliform rash, papulovesicular exanthem, chilbain-like acral pattern, livedo reticularis and purpuric "vasculitic" pattern. Chilblains and Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children are also cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.