The Black Stone is a rock set into the eastern corner of the Kaaba, the ancient building in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is revered by Muslims as an Islamic relic which, according to Muslim tradition, dates back to the time of Adam and Eve.

Bakkah, is a place mentioned in sura 3, ayah 96 of the Qur'an, a verse sometimes translated as: " Verily the first House set apart unto mankind was that at Bakkah, blest, and a guidance unto the worlds",

The Umrah is an Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca that can be undertaken at any time of the year, in contrast to the Ḥajj, which has specific dates according to the Islamic lunar calendar.

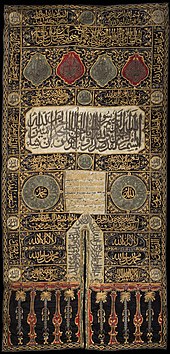

Kiswa is the cloth that covers the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is draped annually on the 9th day of the month of Dhu al-Hijjah, the day pilgrims leave for the plains of Mount Arafat during the Hajj. A procession traditionally accompanies the kiswa to Mecca, a tradition dating back to the 12th century. The term kiswa has multiple translations, with common ones being 'robe' or 'garment'. Due to the iconic designs and the quality of materials used in creating the kiswa, it is considered one of the most sacred objects in Islamic art, ritual, and worship.

The holiest sites in Islam are predominantly located in the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant. While the significance of most places typically varies depending on the Islamic sect, there is a consensus across all mainstream branches of the religion that affirms three cities as having the highest degree of holiness, in descending order: Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. Mecca's Al-Masjid al-Haram, Al-Masjid an-Nabawi in Medina, and Al-Masjid al-Aqsa in Jerusalem are all revered by Muslims as sites of great importance.

The Ministry of Awqaf of Egypt is one of ministries in the Egyptian government and is in charge of religious endowments. Religious endowments, awqaf, are similar to common law trusts where the trustee is the mosque or individual in charge of the waqf and the beneficiary is usually the community as a whole. Examples of waqfs are of a plot of land, a market, a hospital, or any other building that would aid the community.

The Kaaba, also spelled Ka'ba, Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Ka'ba al-Musharrafa, is a stone building at the center of Islam's most important mosque and holiest site, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is considered by Muslims to be the Bayt Allah and is the qibla for Muslims around the world. The current structure was built after the original building was damaged by fire during the siege of Mecca by Umayyads in 683.

The Maqām Ibrāhīm is a small square stone associated with Ibrahim (Abraham), Ismail (Ishmael) and their building of the Kaaba in what is now the Great Mosque of Mecca in the Hejazi region of Saudi Arabia. According to Islamic tradition, the imprint on the stone came from Abraham's feet.

Masjid al-Haram, also known as the Grand Mosque or the Great Mosque of Mecca, is a mosque enclosing the vicinity of the Kaaba in Mecca, in the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia. It is a site of pilgrimage in the Hajj, which every Muslim must do at least once in their lives if able, and is also the main phase for the ʿUmrah, the lesser pilgrimage that can be undertaken any time of the year. The rites of both pilgrimages include circumambulating the Kaaba within the mosque. The Great Mosque includes other important significant sites, including the Black Stone, the Zamzam Well, Maqam Ibrahim, and the hills of Safa and Marwa.

The hajj is a pilgrimage to Mecca performed by millions of Muslims every year, coming from all over the Muslim world. Its history goes back many centuries. The present pattern of the Islamic Hajj was established by Islamic prophet Muhammad, around 632 CE, who reformed the existing pilgrimage tradition of the pagan Arabs. According to Islamic tradition, the hajj dates from thousands of years earlier, from when Abraham, upon God's command, built the Kaaba. This cubic building is considered the most holy site in Islam and the rituals of the hajj include walking repeatedly around it.

Amir al-hajj was the position and title given to the commander of the annual Hajj pilgrim caravan by successive Muslim empires, from the 7th century until the 20th century. Since the Abbasid period, there were two main caravans, one departing from Damascus and the other from Cairo. Each of the two annual caravans was assigned an amir al-hajj whose main duties were securing funds and provisions for the caravan, and protecting it along the desert route to the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina in the Hejaz.

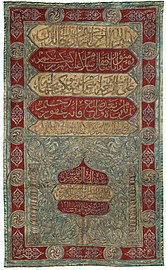

Embroidery was an important art in the Islamic world from the beginning of Islam until the Industrial Revolution disrupted traditional ways of life.

Muḥyi al-Dīn Lārī, died 1521 or 1526–7, was a 16th-century miniaturist and writer, best known for his Kitab Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn, a guidebook to the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

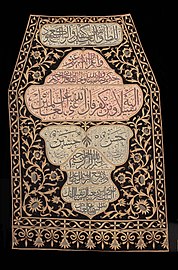

The Khalili Collection of the Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage is a private collection of around 5,000 items relating to the Hajj, the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca which is a religious duty in Islam. It is one of eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by the British-Iranian scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser Khalili; each collection is considered among the most important in its field. The collection's 300 textiles include embroidered curtains from the Kaaba, the Station of Abraham, the Mosque of the Prophet Muhammad and other holy sites, as well as textiles that would have formed part of pilgrimage caravans from Egypt or Syria. It also has illuminated manuscripts depicting the practice and folklore of the Hajj as well as photographs, art pieces, and commemorative objects relating to the Hajj and the holy sites of Mecca and Medina.

The Anis Al-Hujjaj is a seventeenth-century literary work by Safi ibn Vali, an official of the Mughal court in what is now India. Written in Persian, it describes the Hajj undertaken by him in 1677 AD and it gives advice to pilgrims. Its illustrations depict pilgrims travelling to the holy sites and taking part in the rituals of the Hajj. They are also a visual guide to significant places and people.

A mahmal is a ceremonial passenger-less litter that was carried on a camel among caravans of pilgrims on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca which is a sacred duty in Islam. It symbolised the political power of the sultans who sent it, demonstrating their custody of Islam's holy sites. Each mahmal had an intricately embroidered textile cover, or sitr. The tradition dates back at least to the 13th century and ended in the mid-20th. There are many descriptions and photographs of mahmals from 19th century observers of the Hajj.

A sitara or sitarah is an ornamental curtain used in the sacred sites of Islam. A sitara forms part of the kiswah, the cloth covering of the Kaaba in Mecca. Another sitara adorns the Prophet's Tomb in the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi mosque in Medina. These textiles bear embroidered inscriptions of verses from the Quran and other significant texts. Sitaras have been created annually since the 16th century as part of a set of textiles sent to Mecca. The tradition is that the textiles are provided by the ruler responsible for the holy sites. In different eras, this has meant the Mamluk Sultans, the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire, and presently the rulers of Saudi Arabia. The construction of the sitaras is both an act of religious devotion and a demonstration of the wealth of the rulers who commission them.

Muhammad Sadiq Bey was an Ottoman Egyptian army engineer and surveyor who served as treasurer of the Hajj pilgrim caravan. As a photographer and author, he documented the holy sites of Islam at Mecca and Medina, taking the first ever photographs in what is now Saudi Arabia.

Ahmad Abd al-Ghafur Attar was a Saudi Arabian writer, journalist and poet, best known for his works about 20th-century Islamic challenges. Born in Mecca, capital city of Hejazi Hashemite Kingdom. He received a basic education and graduated from the Saudi Scientific Institute in 1937, took a scholarship for higher studies in Cairo University, then returned to his country and worked in some government offices before devoting himself to literature and research. Attar wrote many works about Arabic linguistic and Islamic studies, and gained fame as a Muslim apologist, Anti-communist and Zionism, he who believed in flexibility of Islamic jurisprudence for modern era. Praised by Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad, he was also noted for his defense of Modern Standard Arabic against colloquial or spoken Arabic. In the 1960s, he established the famous Okaz newspaper and then the Kalimat al-Haqq magazine, which lasted only about eight months. He died at the age of 74 in Jeddah.

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam was an exhibition held at the British Museum in London from 26 January to 15 April 2012. It was the world's first major exhibition telling the story, visually and textually, of the hajj – the pilgrimage to Mecca which is one of the five pillars of Islam. Textiles, manuscripts, historical documents, photographs, and art works from many different countries and eras were displayed to illustrate the themes of travel to Mecca, hajj rituals, and the Kaaba. More than two hundred objects were included, drawn from forty public and private collections in a total of fourteen countries. The largest contributor was David Khalili's family trust, which lent many objects that would later be part of the Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage.