Assam is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of 78,438 km2 (30,285 sq mi). The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur to the east; Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram and Bangladesh to the south; and West Bengal to the west via the Siliguri Corridor, a 22-kilometre-wide (14 mi) strip of land that connects the state to the rest of India. Assamese and Boro are the official languages of Assam, while Bengali is an official language in the three districts of Barak Valley.

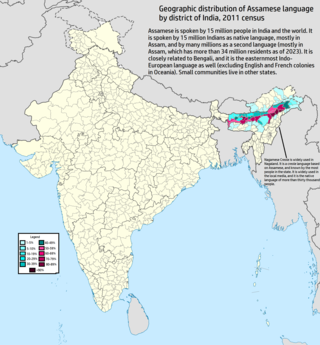

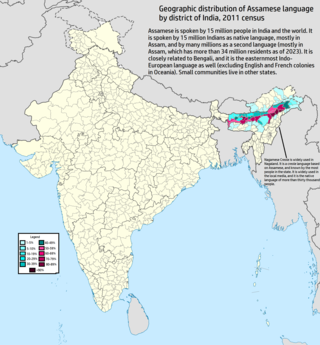

Assamese, also Asamiya ( অসমীয়া), is an Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the north-eastern Indian state of Assam, where it is an official language, and it serves as a lingua franca of the wider region. The easternmost Indo-Iranian language, it has over 15 million speakers according to Ethnologue.

Kamarupi Prakrit is the postulated Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA) Prakrit language used in ancient Kamarupa. This language is the historical ancestor of the Kamatapuri lects and the modern Assamese language; and can be dated prior to 1250 CE, when the proto-Kamta language, the parent of the Kamatapuri lects, began to develop. Though not substantially proven, the existence of the language that predated the Kamatapuri lects and modern Assamese is widely believed to be descended from it.

Buranjis are a class of historical chronicles and manuscripts associated with the Ahom kingdom written initially in Ahom Language and later in Assamese language as well. The Buranjis are an example of historical literature which is rare in India. They bear resemblance to Southeast Asian traditions of historical literature. The Buranjis are generally found in manuscript form, though a number of these manuscripts have been compiled and published, especially in the Assamese language.

The history of Assam is the history of a confluence of people from the east, west, south and the north; the confluence of the Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman (Sino-Tibetan), Tai and Indo-Aryan cultures. Although invaded over the centuries, it was never a vassal or a colony to an external power until the third Burmese invasion in 1821, and, subsequently, the British ingress into Assam in 1824 during the First Anglo-Burmese War.

The Kamata Kingdom emerged in western Kamarupa probably when Sandhya, a ruler of Kamarupanagara, moved his capital west to Kamatapur sometime after 1257 CE. Since it originated in the old seat of the Kamarupa kingdom, and since it covered most of the western parts of it, the kingdom is also sometimes called as Kamarupa-Kamata.

The Assam Movement (1979–1985) was a popular uprising in Assam, India, that demanded the Government of India detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal aliens. Led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) the movement defined a six-year period of sustained civil disobedience campaigns, political instability and widespread ethnic violence. The movement ended in 1985 with the Assam Accord.

Goalpariya is a group of Indo-Aryan dialects spoken in the Goalpara region of Assam, India. Along with Kamrupi, they form the western group of Assamese dialects. The North Bengali dialect is situated to its west, amidst a number of Tibeto-Burman speech communities. The basic characteristic of the Goalpariya is that it is a composite one into which words of different concerns and regions have been amalgamated. Deshi people speak this language and there are around 20 lakhs people.

Assamese literature is the entire corpus of poetry, novels, short stories, plays, documents and other writings in the Assamese language. It also includes the literary works in the older forms of the language during its evolution to the contemporary form and its cultural heritage and tradition. The literary heritage of the Assamese language can be traced back to the c. 9–10th century in the Charyapada, where the earliest elements of the language can be discerned.

Colonial Assam (1826–1947) refers to the period in the history of Assam between the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo and the Independence of India when Assam was under British colonial rule. The political institutions and social relations that were established or severed during this period continue to have a direct effect on contemporary events. The legislature and political alignments that evolved by the end of the British rule continued in the post Independence period. The immigration of farmers from East Bengal and tea plantation workers from Central India continue to affect contemporary politics, most notably that which led to the Assam Movement and its aftermath.

Orunodoi or Arunodoi was the first Assamese-language magazine published monthly from Sibsagar, Assam, in 1846. The magazine created a new era in the world of Assamese literature and gave birth to notable authors such as Anandaram Dhekial Phukan, Hemchandra Barua, Gunabhiram Barua, and Nidhi Levi Farwell. The magazine took the initiative of innovating the then Assamese dialect instead of borrowing words from other languages. The Assamese people got to know about the western world only through this magazine, which opened the gate to the modern literacy in Assam. It mainly included various news related to current affairs, Science, astrology, history and also trivia although Christianity was its main aim. The magazine's publishing ended when the printing press was sold in 1883.

Assamese is part of the easternmost group of the Indo-Aryan languages. History of Assamese literature can largely be classified into three periods, including: Early Assamese period, Middle Assamese period and, Modern Assamese.

Anandaram Dhekial Phukan was one of the pioneers of Assamese literature in the Orunodoi era who joined in the literary revolution initiated by missionaries. He was remembered for his efforts in promoting the Assamese language. He played a major role in reinstating the Assamese language as the official language of Assam.

Kamrupi dialects are a group of regional dialects of Assamese, spoken in the Kamrup region. It formerly enjoyed prestige status. It is one of two western dialect groups of the Assamese language, the other being Goalpariya. Kamrupi is heterogeneous with three subdialects— Barpetia dialect, Nalbariya dialect and Palasbaria dialect.

The Undivided Goalpara district is an erstwhile district of Assam, India, first constituted by the British rulers of Colonial Assam.

Lower Assam division is one of the 5 administrative divisions of Assam in India. It was formed in 1874, consisting of the undivided Kamrup district of Western Assam, undivided Darrang and Nagaon districts of Central Assam and Khasi & Jaintia hills of Meghalaya, created for revenue purposes. The division is under the jurisdiction of a Commissioner, who is stationed at Guwahati. The division currently covers the Western Brahmaputa Valley. Shri Jayant Narlikar, IAS is the current Commissioner of Lower Assam division.

Bongal Kheda was a xenophobic movement in India, which aimed at purging out non-native job competitors by the job-seeking Assamese. Soon after the Independence of India, the Assamese Hindu middle class gained political control in Assam and tried to gain social and economic parity with their competitors, the Bengali Hindu middle class. A significant period of property damage, ethnic policing and even instances of street violence occurred in the region. The exact timeline is disputed, though many authors agree the 1960s saw a height of disruption. It was part of a broader discontent within Assam that would foreshadow the Assamese Language Movement and the greater Assam Movement.

Satish Chandra Kakati was an Indian journalist, writer, the editor of The Assam Tribune, an Assam based English-language daily, and one of the founders of Assam Bani, a vernacular weekly started in 1955 by The Assam Tribune group. He was the vice president of the Editors' Guild of India and authored seven books in Assamese and English. A 2005 recipient of the Kanaklata Barua and Mukunda Kakati Memorial Award, Kakati was awarded the fourth highest civilian award of the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1991.

The Assamese Language Movement refers to a series of political activities demanding the recognition of the Assamese Language as the only sole official language and medium of instruction in the educational institutions of Assam, India.

The Miya people (মিঞা/মিয়া), also known as Nao, refers to the descendants of migrant Bengali Muslims from the modern Mymensingh, Rangpur and Rajshahi Divisions, who settled in the Brahmaputra Valley during the British colonisation of Assam in the 20th-century. Their immigration was encouraged by the Colonial British Government from Bengal Province during 1757 to 1942 and the movement continued till 1947.