Related Research Articles

Aristotle was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science.

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria and lived and taught in Athens at the beginning of the 3rd century, where he held a position as head of the Peripatetic school. He wrote many commentaries on the works of Aristotle, extant are those on the Prior Analytics, Topics, Meteorology, Sense and Sensibilia, and Metaphysics. Several original treatises also survive, and include a work On Fate, in which he argues against the Stoic doctrine of necessity; and one On the Soul. His commentaries on Aristotle were considered so useful that he was styled, by way of pre-eminence, "the commentator".

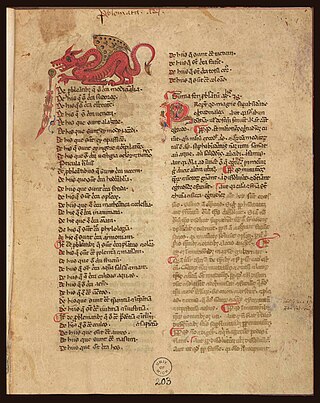

Bartholomaeus Anglicus, also known as Bartholomew the Englishman and Berthelet, was an early 13th-century Scholastic of Paris, a member of the Franciscan order. He was the author of the compendium De proprietatibus rerum, dated c.1240, an early forerunner of the encyclopedia and a widely cited book in the Middle Ages. Bartholomew also held senior positions within the church and was appointed Bishop of Łuków in what is now Poland, although he was not consecrated to that position.

Theophrastus was a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos. His given name was Τύρταμος (Túrtamos); his nickname Θεόφραστος (Theóphrastos) was given by Aristotle, his teacher, for his "divine style of expression".

The Secretum Secretorum or Secreta Secretorum, also known as the Sirr al-Asrar, is a treatise which purports to be a letter from Aristotle to his student Alexander the Great on an encyclopedic range of topics, including statecraft, ethics, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, magic, and medicine. The earliest extant editions claim to be based on a 9th-century Arabic translation of a Syriac translation of the lost Greek original. It is a pseudo-Aristotelian work. Modern scholarship finds it likely to have been written in the 10th century in Arabic. Translated into Latin in the mid-12th century, it was influential among European intellectuals during the High Middle Ages.

The works of Aristotle, sometimes referred to by modern scholars with the Latin phrase Corpus Aristotelicum, is the collection of Aristotle's works that have survived from antiquity.

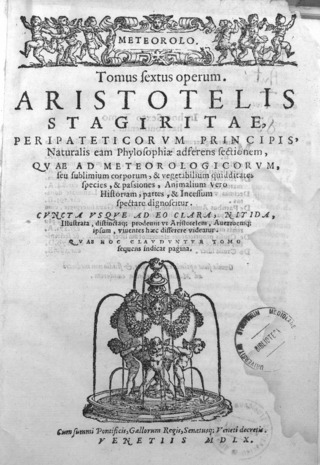

Meteorology is a treatise by Aristotle. The text discusses what Aristotle believed to have been all the affections common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the Earth and the affections of its parts. It includes early accounts of water evaporation, earthquakes, and other weather phenomena.

Science in classical antiquity encompasses inquiries into the workings of the world or universe aimed at both practical goals as well as more abstract investigations belonging to natural philosophy. Classical antiquity is traditionally defined as the period between 8th century BC and the 6th century AD, and the ideas regarding nature that were theorized during this period were not limited to science but included myths as well as religion. Those who are now considered as the first scientists may have thought of themselves as natural philosophers, as practitioners of a skilled profession, or as followers of a religious tradition. Some of the more widely known figures active in this period include Hippocrates, Aristotle, Euclid, Archimedes, Hipparchus, Galen, and Ptolemy. Their contributions and commentaries spread throughout the Eastern, Islamic, and Latin worlds and contributed to the birth of modern science. Their works covered many different categories including mathematics, cosmology, medicine, and physics.

On the Universe is a theological and scientific treatise included in the Corpus Aristotelicum but usually regarded as spurious. It was likely published between 3rd century BCE and the 2nd century CE. The work discusses cosmological, geological, and meteorological subjects, alongside a consideration of the role an independent god plays in maintaining the universe.

Corpuscularianism is a set of theories that explain natural transformations as a result of the interaction of particles. It differs from atomism in that corpuscles are usually endowed with a property of their own and are further divisible, while atoms are neither. Although often associated with the emergence of early modern mechanical philosophy, and especially with the names of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, corpuscularian theories can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.

Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their work to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known as pseudepigrapha. The term Corpus Aristotelicum covers both the authentic and spurious works of Aristotle.

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century. These areas had been under Muslim rule for a considerable time, and still had substantial Arabic-speaking populations to support their search. The combination of this accumulated knowledge and the substantial numbers of Arabic-speaking scholars there made these areas intellectually attractive, as well as culturally and politically accessible to Latin scholars. A typical story is that of Gerard of Cremona, who is said to have made his way to Toledo, well after its reconquest by Christians in 1085, because he:

arrived at a knowledge of each part of [philosophy] according to the study of the Latins, nevertheless, because of his love for the Almagest, which he did not find at all amongst the Latins, he made his way to Toledo, where seeing an abundance of books in Arabic on every subject, and pitying the poverty he had experienced among the Latins concerning these subjects, out of his desire to translate he thoroughly learnt the Arabic language.

During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was at its cultural peak, supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant. These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of Arabic texts in astronomy, mathematics, science, and medicine. Translation of Arabic philosophical texts into Latin "led to the transformation of almost all philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world", with a particularly strong influence of Muslim philosophers being felt in natural philosophy, psychology and metaphysics. Other contributions included technological and scientific innovations via the Silk Road, including Chinese inventions such as paper, compass and gunpowder.

Commentaries on Aristotle refers to the great mass of literature produced, especially in the ancient and medieval world, to explain and clarify the works of Aristotle. The pupils of Aristotle were the first to comment on his writings, a tradition which was continued by the Peripatetic school throughout the Hellenistic period and the Roman era. The Neoplatonists of the Late Roman Empire wrote many commentaries on Aristotle, attempting to incorporate him into their philosophy. Although Ancient Greek commentaries are considered the most useful, commentaries continued to be written by the Christian scholars of the Byzantine Empire and by the many Islamic philosophers and Western scholastics who had inherited his texts.

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient Babylonia, the ancient Greco-Roman world, ancient and medieval China, and Sanskrit texts from ancient India. Books on the subject included the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder which not only described many different minerals but also explained many of their properties. The German Renaissance specialist Georgius Agricola wrote works such as De re metallica and De Natura Fossilium which began the scientific approach to the subject. Systematic scientific studies of minerals and rocks developed in post-Renaissance Europe. The modern study of mineralogy was founded on the principles of crystallography and microscopic study of rock sections with the invention of the microscope in the 17th century.

The Rhetoric to Alexander is a treatise traditionally attributed to Aristotle. It is now generally believed to be the work of Anaximenes of Lampsacus.

The Situations and Names of Winds is a spurious fragment traditionally attributed to Aristotle. The brief text lists winds blowing from twelve different directions and their alternative names used in different places. According to the manuscript version of the work, The Situations and Names of Winds is an extract from a larger work entitled On Signs likely written by a pseudo-Aristotle of the peripatetic school. Situations is notable as an ancient text which reproduces the concepts of the Anemoi or "wind gods" and classical compass winds, both of which have been historical components of western culture.

On Plants is a botanical treatise included in the Corpus Aristotelicum but usually regarded as Pseudo-Aristotle. In 1923, a manuscript containing the original Arabic translation from Greek, as done by Ishaq ibn Hunayn, was discovered in Istanbul, which led scholars to conclude the work was likely an exegesis/commentary by philosopher Nicolaus of Damascus on a treatise by Aristotle which is now lost. On Plants describes the nature and origins of plants.

Abū al-Khayr al-Ḥasan ibn Suwār ibn Bābā ibn Bahnām, called Ibn al-Khammār, was an East Syriac Christian philosopher and physician who taught and worked in Baghdad. He was a prolific translator from Syriac into Arabic and also wrote original works of philosophy, ethics, theology, medicine and meteorology.

Bartholomew of Messina was a Sicilian scholar who worked as a translator of Greek into Latin at the court of King Manfred of Sicily.

References

- 1 2 3 Vermij 1998, p. 324.

- ↑ Crombie 1995, p. 133.

- 1 2 Peters 1968, p. 57–58.

- ↑ Crombie 1995, p. 133–135.

- ↑ Vermij 1998, p. 324–325.

- ↑ Vermij 1998, p. 328.