The Almagest is a 2nd-century mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy in Koine Greek. One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canonized a geocentric model of the Universe that was accepted for more than 1,200 years from its origin in Hellenistic Alexandria, in the medieval Byzantine and Islamic worlds, and in Western Europe through the Middle Ages and early Renaissance until Copernicus. It is also a key source of information about ancient Greek astronomy.

The history of geodesy (/dʒiːˈɒdɪsi/) began during antiquity and ultimately blossomed during the Age of Enlightenment.

Tractatus is Latin for "treatise". It may refer to:

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like gems set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

In astronomy, the fixed stars are the luminary points, mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the background. This is in contrast to those lights visible to naked eye, namely planets and comets, that appear to move slowly among those "fixed" stars.

Johannes de Sacrobosco, also written Ioannes de Sacro Bosco, later called John of Holywood or John of Holybush, was a scholar, monk, and astronomer who taught at the University of Paris.

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī, known as Mashallah, was an 8th century Persian Jewish astrologer, astronomer, and mathematician. Originally from Khorasan, he lived in Basra during the reigns of the Abbasid caliphs al-Manṣūr and al-Ma’mūn, and was among those who introduced astrology and astronomy to Baghdad. The bibliographer ibn al-Nadim described Mashallah "as virtuous and in his time a leader in the science of jurisprudence, i.e. the science of judgments of the stars". Mashallah served as a court astrologer for the Abbasid caliphate and wrote works on astrology in Arabic. Some Latin translations survive.

Lynn Thorndike was an American historian of medieval science and alchemy. He was the son of a clergyman, Edward R. Thorndike, and the younger brother of Ashley Horace Thorndike, an American educator and expert on William Shakespeare, and Edward Lee Thorndike, known for being the father of modern educational psychology.

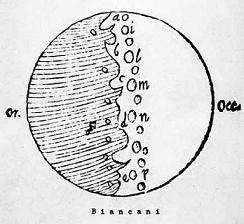

Giuseppe Biancani, SJ (1566–1624) was an Italian Jesuit astronomer, mathematician, and selenographer, after whom the crater Blancanus on the Moon is named.

In the history of science, the clockwork universe compares the universe to a mechanical clock. It continues ticking along, as a perfect machine, with its gears governed by the laws of physics, making every aspect of the machine predictable.

Ancient Greek astronomy is the astronomy written in the Greek language during classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and late antique eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to ethnic Greeks, as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world following the conquests of Alexander. This phase of Greek astronomy is also known as Hellenistic astronomy, while the pre-Hellenistic phase is known as Classical Greek astronomy. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many of the Greek and non-Greek astronomers working in the Greek tradition studied at the Museum and the Library of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Solomon ben Abraham Abigdor, born in Provence in 1384, was a Hebrew translator, physician, and mystic.

Petrus de Dacia, also called Philomena and Peder Nattergal, was a Danish scholar who lived in the 13th century. He worked mainly in Paris and Italy, writing in Latin. He published a calendar of new moon dates for the years 1292-1367. In 1292, he published a book on mathematics that contained a new method for the calculation of cubic roots. He also described a mechanical instrument to predict solar and lunar eclipses as seen from Paris.

Erasmus Oswald Schreckenfuchs (1511–1579) was an Austrian humanist, astronomer and Hebraist.

Francesco Capuano Di Manfredonia was an Italian astronomer, professor, and member of the clergy. Up until the 1880s there wasn't a lot known about Capuano, and the little bit that was known was derived directly from his printed works.

Jacques du Chevreul was a French mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher.

Pedro Sánchez Ciruelo was a Spanish philosopher, theologian, mathematician, astrologer, astronomer and writer on topics of natural philosophy.

André do Avelar also known as "Andre dauellar" was an author and professor who published astronomical works at the University of Coimbra. His works sought to explain astronomy, astrology, and the calendar year to the people of Lisbon. Despite his esteem he would later be sentenced to life in prison by the Inquisition as he was accused of being a Judaizer.

Johannes Paulus Lauratius de Fundis was a medieval astronomer and professor of astrology in Bologna. He is known for several manuscript works including Tractatus reprobationis eorum que scripsit Nicolaus Orrem (1451) and Nova theorica planetarum.