The Grateful Dead was an American rock band formed in Palo Alto, California, in 1965. Known for their eclectic style that fused elements of rock, blues, jazz, folk, country, bluegrass, rock and roll, gospel, reggae, and world music with psychedelia, the band is famous for improvisation during their live performances, and for their devoted fan base, known as "Deadheads". According to the musician and writer Lenny Kaye, the music of the Grateful Dead "touches on ground that most other groups don't even know exists." For the range of their influences and the structure of their live performances, the Grateful Dead are considered "the pioneering godfathers of the jam band world".

Mathis James Reed was an American blues musician and songwriter. His particular style of electric blues was popular with a wide variety of audiences. Reed's songs such as "Honest I Do" (1957), "Baby What You Want Me to Do" (1960), "Big Boss Man" (1961), and "Bright Lights, Big City" (1961) appeared on both Billboard magazine's R&B and Hot 100 singles charts.

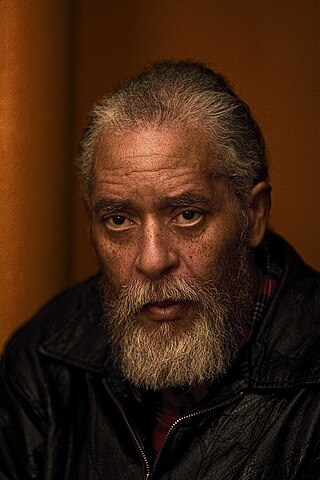

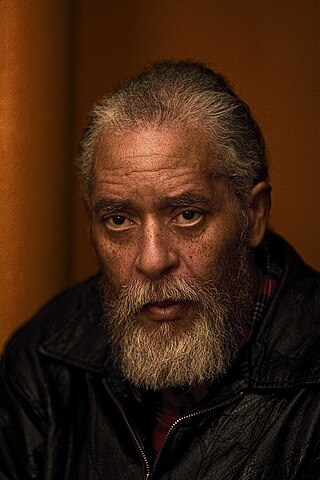

Ronald Charles McKernan, known as Pigpen, was an American musician. He was a founding member of the San Francisco band the Grateful Dead and played in the group from 1965 to 1972.

Paul Pena was an American singer, songwriter and guitarist.

Willie Johnson, commonly known as Blind Willie Johnson, was an American gospel blues singer and guitarist. His landmark recordings completed between 1927 and 1930, thirty songs in all, display a combination of powerful chest voice singing, slide guitar skills and originality that has influenced generations of musicians. His records sold well though as a street performer and preacher, he had little wealth in his lifetime. His life was poorly documented, but over time, music historians such as Samuel Charters have uncovered more about him and his five recording sessions.

Gary D. Davis, known as Reverend Gary Davis and Blind Gary Davis, was a blues and gospel singer who was also proficient on the banjo, guitar and harmonica. Born in Laurens, South Carolina and blind since infancy, Davis first performed professionally in the Piedmont blues scene of Durham, North Carolina in the 1930s, then converted to Christianity and became a minister. After moving to New York in the 1940s, Davis experienced a career rebirth as part of the American folk music revival that peaked during the 1960s. Davis' most notable recordings include "Samson and Delilah" and "Death Don't Have No Mercy".

Henry Thomas was an American country blues singer, songster and musician. Although his recording career, in the late 1920s, was brief, Thomas influenced performers including Bob Dylan, Taj Mahal, the Lovin' Spoonful, the Grateful Dead, and Canned Heat. Often billed as "Ragtime Texas", Thomas's style is an early example of what later became known as Texas blues guitar.

Fillmore West 1969: The Complete Recordings is a 10-CD live album by the rock band the Grateful Dead. It contains four complete concerts recorded on February 27, February 28, March 1, and March 2, 1969, at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. The album was remixed from the original 16-track concert soundboard tapes. It was released as a box set in November 2005, in a limited edition of 10,000 copies.

"Cocaine Blues" is a Western swing song written by Troy Junius Arnall, a reworking of the traditional song "Little Sadie." Roy Hogsed recorded a well known version of the song in 1947.

Stefan Grossman is an American acoustic fingerstyle guitarist and singer, music producer and educator, and co-founder of Kicking Mule records. He is known for his instructional videos and Vestapol line of videos and DVDs.

"Mercy, Mercy" is a soul song first recorded by American singer/songwriter Don Covay in 1964. It established Covay's recording career and influenced later vocal and guitar styles. The songwriting is usually credited to Covay and Ron Alonzo Miller, although other co-writers' names have also appeared on various releases.

Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions is an American folk music album. It was recorded live by the band of the same name at the Top of the Tangent coffee house in Palo Alto, California in July, 1964, and released in 1999.

Gospel blues is a form of blues-based gospel music that has been around since the inception of blues music. It combines evangelistic lyrics with blues instrumentation, often blues guitar accompaniment.

Thomas Griffin Winslow was an American folk singer and writer known as a "disciple" of Reverend Gary Davis and a former member of Pete Seeger's band. He performed with his family as The Winslows and recorded with Al Polito. His career as a performing artist lasted over forty years. He was most notable as the composer of "Hey Looka Yonder ", a folk song that has been the anthem of the Sloop Clearwater.

Roy Book Binder is an American blues guitarist, singer-songwriter and storyteller. A student and friend of the Rev. Gary Davis, he is equally at home with blues and ragtime. He is known to shift from open tunings to slide arrangements to original compositions, with both traditional and self-styled licks. His storytelling is another characteristic that makes his style unique.

"You Don't Love Me" is a rhythm and blues-influenced blues song recorded by American musician Willie Cobbs in 1960. Adapted from Bo Diddley's 1955 song "She's Fine She's Mine", it is Cobbs' best-known song and features a guitar figure and melody that has appealed to musicians in several genres.

The Country Blues is a seminal album released on Folkways Records in 1959, catalogue RF 1. Compiled by Samuel Charters from 78-rpm recordings, it accompanied his book of the same name to provide examples of the music discussed. Both the book and the album were key documents in the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, and many of its songs would either be incorporated into new compositions by later musicians, or covered outright.

Live at New Orleans House: Berkeley, CA 09/69 is an album by the American rock band Hot Tuna. As the name suggests, it was recorded live at the New Orleans House music venue in Berkeley, California in September 1969. It was released in April 2010.

Harlem Street Singer is a studio album by the American gospel blues singer-guitarist Blind Gary Davis, recorded in 1960 and released on the Bluesville label in December of that year. It features perhaps his best-known song "Death Don't Have No Mercy".

Butt Naked Free is an album by the American musician Guy Davis, released in 2000. The album title was inspired by a dance performed by Davis's son during the recording sessions, although it was ultimately selected by Red House Records. Davis supported the album with North American and United Kingdom tours. Butt Naked Free was nominated for a W. C. Handy Award for best "Acoustic Blues Album". The album was a success on public and college radio stations.