Related Research Articles

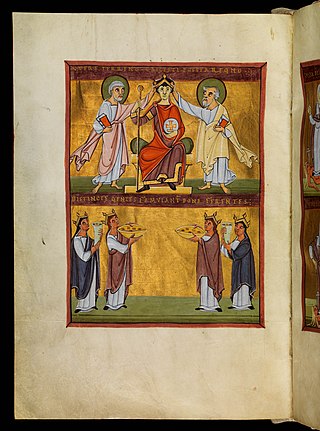

Theophanu was empress of the Holy Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Otto II, and regent of the Empire during the minority of their son, Emperor Otto III, from 983 until her death in 991. She was the niece of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes. She was known to be a forceful and capable ruler. Her status in the history of the Empire in many ways was exceptional. According to Wilson, "She became the only consort to receive the title 'co-empress', and it was envisaged she would succeed as sole ruler if Otto II died without a son."

Philip of Swabia was a member of the House of Hohenstaufen and King of Germany from 1198 until his assassination.

Hildegard, was a Frankish queen consort who was the second wife of Charlemagne and mother of Louis the Pious. Little is known about her life because like all other women related to Charlemagne, she became notable only from a political background with records on her parentage, wedding, death and role as a mother.

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, especially after the kingship passed from Frankish kings to the Saxon Ottonian dynasty in 919. The king was elected, initially by the rulers of the stem duchies, who generally chose one of their own. After 962, when Otto I was crowned emperor, East Francia formed the bulk of the Holy Roman Empire, which also included the Kingdom of Italy and, after 1032, the Kingdom of Burgundy.

In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.

Matilda, also known as Mathilda and Mathilde, was a German regent, and the first Princess-Abbess of Quedlinburg. She served as regent of Germany for her brother during his absence in 967, and as regent during the minority of her nephew from 984.

Henry V was King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, as the fourth and last ruler of the Salian dynasty. He was made co-ruler by his father, Henry IV, in 1098.

The Gunthertuch is a Byzantine silk tapestry which represents the triumphal return of a Byzantine Emperor from a victorious campaign. The piece was purchased, or possibly received as a gift, by Gunther von Bamberg, Bishop of Bamberg, during his 1064–65 pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Gunther died on his return journey, and was buried with it in the Bamberg Cathedral. The fabric was rediscovered in 1830, and is now exhibited in the Bamberg Diocesan Museum.

The Saxon revolt refers to the struggle between the Salian dynasty ruling the Holy Roman Empire and the rebel Saxons during the reign of Henry IV. The conflict reached its climax in the period from summer 1073 until the end of 1075, in a rebellion that involved several clashes of arms.

The war between Clusium and Aricia was a military conflict in central Italy that took place around 508 BC.

A Hoftag was the name given to an informal and irregular assembly convened by the King of the Romans, the Holy Roman Emperor or one of the Princes of the Empire, with selected chief princes within the empire. Early scholarship also refers to these meetings as imperial diets (Reichstage), even though these gatherings were not really about the empire in general, but with matters concerning their individual rulers. In fact, the legal institution of the imperial diet appeared much later.

The lokator was a medieval sub-contractor, who was responsible to a territorial lord or landlord for the clearing, survey and apportionment of land that was to be settled. In addition, he hired settlers for this purpose, provided their means of subsistence during the transitional period and made materiel and implements available, such as seed, draught animals, iron ploughs, etc. He thus played a key role during the establishment of new towns and villages, as well as the clearing of uncultivated land during the phase of internal colonisation (Binnenkolonisation) in North German and the German Ostsiedlung and participated in its success.

The Ewiger Landfriede of 1495, passed by Maximilian I, German king and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was the definitive and everlasting ban on the medieval right of vendetta (Fehderecht). In fact, despite being officially outlawed, feuds continued in the territory of the empire until well into the 16th century.

Michael Matheus is a German historian.

The Burgfrieden or Burgfriede was a German medieval term that referred to imposition of a state of truce within the jurisdiction of a castle, and sometimes its estate, under which feuds, i.e. conflicts between private individuals, were forbidden under threat of the imperial ban.

In the Holy Roman Empire, the Great Interregnum was a period of time following the death of Frederick II where the succession of the Holy Roman Empire was contested and fought over between pro- and anti-Hohenstaufen factions. Starting around 1250 with the death of Frederick II, conflict over who was the rightful emperor and King of the Romans would continue into the 1300s until Charles IV of Luxembourg was elected emperor and secured succession for his son Wenceslaus. This period saw a multitude of emperors and kings be elected or propped up by rival factions and princes, with many kings and emperors having short reigns or reigns that became heavily contested by rival claimants.

Gerd Althoff is a German historian of the Early and High Middle Ages. He presents himself as a researcher into the "political rules of the game" in the Middle Ages. He has held professorships at Münster, Gießen (1990–1995) and Bonn (1995–1997).

Matthias Untermann is a German art historian and medieval archaeologist.

Otto I, also called Otto the Great, is seen by many as one of the greatest medieval rulers. His name is usually associated with the foundation, the victory in the Battle of Lechfeld gained him, according to historian Jim Bradburn, a reputation as the great champion of Christendom, and the Ottonian Renaissance. Although historians in different eras have never denied his reputation as a successful ruler, the image of the nationalist political strongman which was usually perceived during the nineteenth century has been questioned by more recent sources. Modern historians explore the emperor's capability as a consensus builder, as well as the participation of princes in contemporary politics and the important roles played by female actors and his advisors in his endeavors. Mentioned also is that Otto did have a strong character. In many cases, Otto chose his own way, which also led to rebellions. He often emerged victorious in the end.

A royal election took place on 27 May 983 in Verona in the Kingdom of Italy. The three-year-old Otto III was elected to co-rule in the kingdoms of Italy and Germany with his father, the Emperor Otto II.

References

- ↑ Adolph Berger, s.v. "Deditio", Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philosophical Society, 1953), p. 427.

- ↑ L. De Ligt, "Provincial Dediticii in the Epigraphic Lex Agraria of 111 BC?" Classical Quarterly 58:1 (2008), pp. 358–359, citing Livy 1.38.

- ↑ De Ligt, "Provincial Dediticii," p. 359.

- ↑ Zbigniew Dalewski (21 April 2008). Ritual and Politics: Writing the History of a Dynastic Conflict in Medieval Poland. BRILL. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-90-474-3337-8.

- ↑ Vučetić Martin Marko (2013). "Das ritual der unterwerfung Stefan Nemanjas unter Maunel I. Komnenos (1172)" (PDF). Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. 50 (1): 493–503. doi:10.2298/ZRVI1350493V. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-16.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Die Macht der Rituale. Symbolik und Herrschaft im Mittelalter (Darmstadt 2003), pp. 13, 32, 42, 53-57, 68, 76-83, 108, 133, 136, 154, 170-187.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Das Privileg der deditio. Formen gütlicher Konfliktbeendigung in der mittelalterlichen Adelsgesellschaft. In: Ders.: Spielregeln der Politik im Mittelalter. Kommunikation in Frieden und Fehde. Darmstadt 1997, pp. 27-52, 99–125

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: "Colloquium familiare – Colloquium secretum – Colloquium publicum. Beratung im politischen Leben des früheren Mittelalters", in: Frühmittelalterliche Studien vol. 24 (1990) pp. 145–167.

- ↑ Timothy Reuter (2001). "Rules of the game in Medieval Politics" (PDF). book review of a volume of eleven articles - most of which had already been individually published in learned journals - by Gerhard Althoff. Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland (German Historical Institute London Bulletin), Bonn. pp. 40–46. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff (2011). Das hochmittelalterliche Königtum. Akzente einer unabgeschlossenen Neubewertung. pp. 77–98, 82, 99–125.