The Gulf of Tonkin incident was an international confrontation that led to the United States engaging more directly in the Vietnam War. It consisted of a confrontation on August 2, 1964, when United States forces were carrying out covert operations close to North Vietnamese territorial waters and North Vietnamese forces responded. The United States government falsely claimed that a second incident occurred on August 4, 1964, between North Vietnamese and United States ships in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. Originally, US military claims blamed North Vietnam for the confrontation and the ostensible, but in fact imaginary, incident on August 4. Later investigation revealed that the second attack never happened; the official American claim is that it was based mostly on erroneously interpreted communications intercepts. The National Security Agency, a subsidiary of the US Defense Department, deliberately skewed intelligence to create the impression that an attack had been carried out.

Robert Strange McNamara was an American business executive and the eighth United States secretary of defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the longest serving secretary of defense, having remained in office over seven years. He played a major role in promoting the U.S.'s involvement in the Vietnam War. McNamara was responsible for the institution of systems analysis in public policy, which developed into the discipline known today as policy analysis.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the National Security Council on military matters. The composition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is defined by statute and consists of a chairman (CJCS), a vice chairman (VJCS), the chiefs of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and the chief of the National Guard Bureau. Each of the individual service chiefs, outside their JCS obligations, works directly under the secretaries of their respective military departments, e.g. the secretary of the Army, the secretary of the Navy, and the secretary of the Air Force.

Maxwell Davenport Taylor was a senior United States Army officer and diplomat of the mid-20th century. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Airborne Division, nicknamed "The Screaming Eagles."

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces and the principal military advisor to the president, the National Security Council, the Homeland Security Council, and the secretary of defense. While the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff outranks all other commissioned officers, the chairman is prohibited by law from having operational command authority over the armed forces; however, the chairman assists the president and the secretary of defense in exercising their command functions.

General John Paul McConnell was the sixth Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. As chief of staff, McConnell served in a dual capacity. He was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff which, as a body, acts as the principal military adviser to the President of the United States, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense. In his other capacity, he was responsible to the Secretary of the Air Force for managing the vast human and materiel resources of the world's most powerful aerospace force.

Herbert Raymond McMaster is a retired United States Army lieutenant general who served as the 25th United States National Security Advisor from 2017 to 2018. He is also known for his roles in the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Interservice rivalry is rivalry between different branches of a country's armed forces. This may include competition between land, marine, naval, coastal, air, or space forces.

The Taylor-Rostow Report was a report prepared in November 1961 on the situation in Vietnam in relation to Vietcong operations in South Vietnam. The report was written by General Maxwell Taylor, military representative to President John F. Kennedy, and Deputy National Security Advisor W.W. Rostow. Kennedy sent Taylor and Rostow to Vietnam in October 1961 to assess the deterioration of South Vietnam’s military position and the government's morale. The report called for improved training of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops, an infusion of American personnel into the South Vietnamese government and army, greater use of helicopters in counterinsurgency missions against North Vietnamese communists, consideration of bombing the North, and the commitment of 6,000-8,000 U.S. combat troops to Vietnam, albeit initially in a logistical role. The document was significant in that it seriously escalated the Kennedy Administration's commitment to Vietnam. It was also seen historically as having misdiagnosed the root of the Vietnam conflict as primarily a military rather than a political problem.

The National Security Council Working Group on South Vietnam/Southeast Asia was founded in the wake of the election Lyndon B. Johnson's election campaign against Barry Goldwater to explore the different options LBJ could take in Vietnam. William Bundy would later note that this group was "'the most comprehensive' Vietnam policy review 'of any in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations.'"

The 1959 to 1963 phase of the Vietnam War started after the North Vietnamese had made a firm decision to commit to a military intervention in the guerrilla war in the South Vietnam, a buildup phase began, between the 1959 North Vietnamese decision and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which led to a major US escalation of its involvement. Vietnamese communists saw this as a second phase of their revolution, the US now substituting for the French.

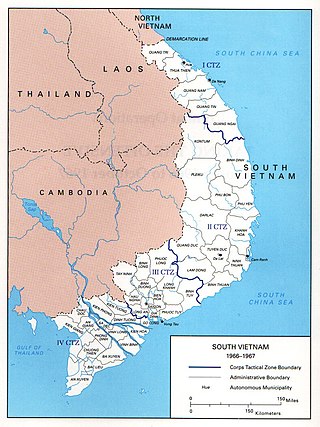

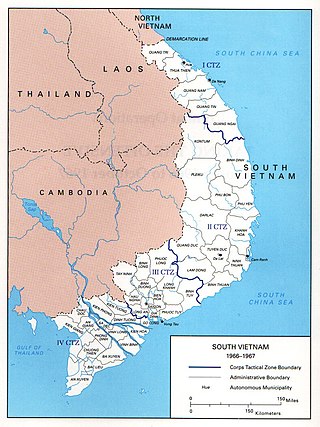

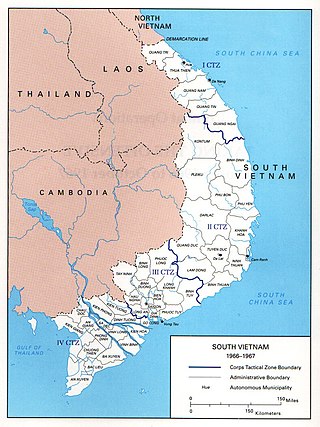

During the Cold War in the 1960s, the United States and South Vietnam began a period of gradual escalation and direct intervention referred to as the "Americanization" of joint warfare in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. At the start of the decade, United States aid to South Vietnam consisted largely of supplies with approximately 900 military observers and trainers. After the assassination of both Ngo Dinh Diem and John F. Kennedy close to the end of 1963 and Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 and amid continuing political instability in the South, the Lyndon Johnson Administration made a policy commitment to safeguard the South Vietnamese regime directly. The American military forces and other anti-communist SEATO countries increased their support, sending large scale combat forces into South Vietnam; at its height in 1969, slightly more than 400,000 American troops were deployed. The People's Army of Vietnam and the allied Viet Cong fought back, keeping to countryside strongholds while the anti-communist allied forces tended to control the cities. The most notable conflict of this era was the 1968 Tet Offensive, a widespread campaign by the communist forces to attack across all of South Vietnam; while the offensive was largely repelled, it was a strategic success in seeding doubt as to the long-term viability of the South Vietnamese state. This phase of the war lasted until the election of Richard Nixon and the change of U.S. policy to Vietnamization, or ending the direct involvement and phased withdrawal of U.S. combat troops and giving the main combat role back to the South Vietnamese military.

The defeat of the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in a battle in January set off a furious debate in the United States on the progress being made in the war against the Viet Cong (VC) in South Vietnam. Assessments of the war flowing into the higher levels of the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. were wildly inconsistent, some citing an early victory over the VC, others a rapidly deteriorating military situation. Some senior U.S. military officers and White House officials were optimistic; civilians of the Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), junior military officers, and the media were decidedly less so. Near the end of the year, U.S. leaders became more pessimistic about progress in the war.

National Security Action Memorandum Number 263 (NSAM-263) was a national security directive approved on 11 October 1963 by United States President John F. Kennedy. The NSAM approved recommendations by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell Taylor. McNamara and Taylor's recommendations included an appraisal that "great progress" was being made in the Vietnam War against Viet Cong insurgents, that 1,000 military personnel could be withdrawn from South Vietnam by the end of 1963, and that a "major part of the U.S. military task can be completed by the end of 1965." The U.S. at this time had more than 16,000 military personnel in South Vietnam.

The Sigma war games were a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. The games were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future events in the region. In almost all runs, the outcome was either a communist win, or a stalemate that led to protests in the US.

The Sigma I-62 war game, played in February 1962, was the first of a series of classified high level war games played in the Pentagon during the 1960s to strategize the conduct of the burgeoning Vietnam War. These simulations were designed to replicate then-current conditions in Indochina, with an aim toward predicting future foreign affairs events. The conclusion drawn from Sigma I-62 was that American intervention in Vietnam would be unsuccessful.

The Sigma I-64 war game, one of the Sigma war games, was played from 6 to 9 April 1964. Its purpose was to test scenarios of escalation of warfare in Vietnam. After rigorous research into information needed to form a scenario, a simulation took place, with knowledgeable officials playing out the roles of actual government decision makers. Participants were drawn from the State Department, Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In Sigma I-64, the scenarios to be examined were the burgeoning Viet Cong insurgency in Vietnam, and the possible use of U.S. air power against it.

National Security Action Memorandum 273 (NSAM-273) was approved by new United States President Lyndon Johnson on November 26, 1963, one day after former President John F. Kennedy's funeral. NSAM-273 resulted from the need to reassess U.S. policy toward the Vietnam War following the overthrow and assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem. The first draft of NSAM-273, completed before Kennedy's death, was approved with minor changes by President Johnson.

The Declaration of Honolulu, 1966 was a communiqué and diplomatic proclamation acceded by foreign diplomats representing the Republic of Vietnam and the United States. The declaration asserted pro-democracy principles for South Vietnam while combating external aggression and insurgency by Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The goals outlined at the conference were a cornerstone to US policy in Vietnam until 1969 when the incoming Nixon administration changed policies towards Vietnam.

The United States foreign policy during the 1963-1969 presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson was dominated by the Vietnam War and the Cold War, a period of sustained geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. Johnson took over after the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, while promising to keep Kennedy's policies and his team.