Related Research Articles

The Ides of March is the day on the Roman calendar marked as the Idus, roughly the midpoint of a month, of Martius, corresponding to 15 March on the Gregorian calendar. It was marked by several major religious observances. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, commonly known in English as Drusus the Elder, was a Roman politician and military commander. He was a patrician Claudian but his mother was from a plebeian family. He was the son of Livia Drusilla and the stepson of her second husband, the Emperor Augustus. He was also brother of the Emperor Tiberius; the father of the Emperor Claudius and general Germanicus; paternal grandfather of the Emperor Caligula, and maternal great-grandfather of the Emperor Nero.

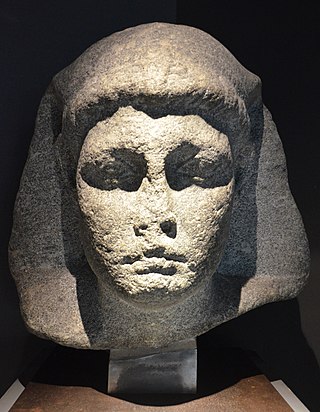

Ptolemy XV Caesar, nicknamed Caesarion, was the last pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt, reigning with his mother Cleopatra VII from 2 September 44 BC until her death by 12 August 30 BC, then as sole ruler until his death was ordered by Octavian.

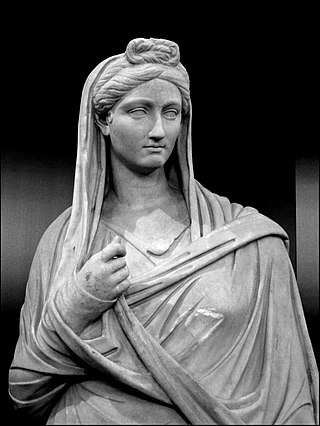

In ancient Roman religion and myth, the Parcae were the female personifications of destiny who directed the lives of humans and gods. They are often called the Fates in English, and their Greek equivalent were the Moirai. They did not control a person's actions except when they are born, when they die, and how much they suffer.

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the change. It can be a simple legal convention or can be part of a ritual or spiritual event.

The praenomen was a personal name chosen by the parents of a Roman child. It was first bestowed on the dies lustricus, the eighth day after the birth of a girl, or the ninth day after the birth of a boy. The praenomen would then be formally conferred a second time when girls married, or when boys assumed the toga virilis upon reaching manhood. Although it was the oldest of the tria nomina commonly used in Roman naming conventions, by the late republic, most praenomina were so common that most people were called by their praenomina only by family or close friends. For this reason, although they continued to be used, praenomina gradually disappeared from public records during imperial times. Although both men and women received praenomina, women's praenomina were frequently ignored, and they were gradually abandoned by many Roman families, though they continued to be used in some families and in the countryside.

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

In ancient Roman religion, Mana Genita or Geneta Mana is an obscure goddess mentioned only by Pliny, Plutarch, and Horace. Both Pliny and Plutarch tell that her rites were carried out by the sacrifice of a puppy or a bitch. Plutarch alone has left some examination of the nature of the goddess, deriving Mana from the Latin verb manare, "to flow", an etymology which the Roman grammarian Verrius Flaccus also relates to the goddess Mania mentioned by Varro, and to the Manes, the souls of the departed. In a Greek equivalence perspective, Plutarch, on account of the bitch sacrifice, loosely connects the goddess to Hekate and in parallel notes that Argive sacrificial practice makes as well for an interesting comparison for her with Eilioneia, meaning the birth goddess Eileithyia. Horace also links her to Eileithyia in carmen saeculare Some modern commentators have elaborated on the "Genita" and "Mana" qualifiers, to suggest she were a goddess who could determine whether infants were born alive or dead. Others have suggested that Horace may be referring to this goddess when he mentions a goddess Genitalis in the Carmen Saeculare. Some have compared it to the Oscan Deiua Geneta, while still others deem that Genita Mana may be only a vague epithet like Bona Dea rather than an actual theonym.

Roman funerary practices include the Ancient Romans' religious rituals concerning funerals, cremations, and burials. They were part of time-hallowed tradition, the unwritten code from which Romans derived their social norms. Elite funeral rites, especially processions and public eulogies, gave the family opportunity to publicly celebrate the life and deeds of the deceased, their ancestors, and the family's standing in the community. Sometimes the political elite gave costly public feasts, games and popular entertainments after family funerals, to honour the departed and to maintain their own public profile and reputation for generosity. The Roman gladiator games began as funeral gifts for the deceased in high status families.

The Amphidromia, in ancient Greece, was a ceremonial feast celebrated on the fifth or seventh day after the birth of a child.

Lustratio was an ancient Greek and ancient Roman purification ritual. It included a procession and in some circumstances the sacrifice of a pig (sus), a ram (ovis), and a bull (taurus) (suovetaurilia). The name is the source of English "lustration".

A naming ceremony is a stage at which a person or persons is officially assigned a name. The methods of the practice differ over cultures and religions. The timing at which a name is assigned can vary from some days after birth to several months or many years.

Gaius is a Latin praenomen, or personal name, and was one of the most common names throughout Roman history. The feminine form is Gaia. The praenomen was used by both patrician and plebeian families, and gave rise to the patronymic gens Gavia. The name was regularly abbreviated C., based on the original spelling, Caius, which dates from the period before the letters "C" and "G" were differentiated. Inverted, Ɔ. stood for the feminine, Gaia.

In the Roman Empire, Rosalia or Rosaria was a festival of roses celebrated on various dates, primarily in May, but scattered through mid-July. The observance is sometimes called a rosatio ("rose-adornment") or the dies rosationis, "day of rose-adornment," and could be celebrated also with violets (violatio, an adorning with violets, also dies violae or dies violationis, "day of the violet[-adornment]"). As a commemoration of the dead, the rosatio developed from the custom of placing flowers at burial sites. It was among the extensive private religious practices by means of which the Romans cared for their dead, reflecting the value placed on tradition (mos maiorum, "the way of the ancestors"), family lineage, and memorials ranging from simple inscriptions to grand public works. Several dates on the Roman calendar were set aside as public holidays or memorial days devoted to the dead.

Childbirth in ancient Rome was dangerous for both the mother and the child. Mothers usually would rely on religious superstition to avoid death. Certain customs such as lying in bed after childbirth and using plants and herbs as relief were also practiced. Midwives assisted the mothers in birth. Once children were born they wouldn’t be given a name until 8 or 9 days after their birth. The number depended on if they were male or female. Once the days had passed, the child would be given a name and a bulla during a ceremony. When a child reached the age of 1, they would gain legal privileges which could lead to citizenship. Children 7 and under were considered infants, and were under the care of women. From a age 8 until they reached adulthood children were expected to help with housework. The age of adulthood was 12 for girls, or 14 for boys. Children would often have a variety of toys to play with. If a child died they could be buried or cremated. Some would be commemorated in Roman religious tradition.

Maureen Carroll is a Canadian archaeologist and academic. She is the Chair in Roman Archaeology at the University of York.

The tollere liberum was an ancient Roman tradition in which a man picked up a newly born infant from the ground and lifted them in the air to display his acceptance of them as part of his household. It was commonly the father, or in some cases the chief of the house, who performed the task. In some variations of the tradition the man would carry them around a portion of earth.

Pupus was an ancient Roman name, meaning "boy", it seems to have been used mainly as a nickname for little children, but there are cases of it being used as proper cognomen for adults and even as a praenomen.

Swaddled babyvotives are figures of babies offered as an entreaty to a god or goddess, for healthy pregnancy and childbirth. They have been recovered from ancient Italian Roman temple sanctuary sites.

References

- ↑ Plutarch, Roman Questions 102.

- ↑ Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," p. 242.

- ↑ Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," p. 251.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.16.36.

- ↑ S. Breemer and J. H. Waszinsk Mnemosyne 3 Ser. 13, 1947, pp. 254–270: on personal destiny as linked to the collation of the dies lustricus.

- ↑ Dixon, Suzanne (2005). Childhood, Class and Kin in the Roman World. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 9781134563197.

- ↑ Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," p. 248.

- ↑ Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," p. 251.

- ↑ Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," pp. 245, 250.

- ↑ Carroll, Maureen (2018). Infancy and Earliest Childhood in the Roman World: 'A Fragment of Time'. Oxford University Press. pp. ?. ISBN 9780192524348.

- ↑ Carroll, Maureen (2018). Infancy and Earliest Childhood in the Roman World: 'A Fragment of Time'. Oxford University Press. pp. ??. ISBN 9780192524348.

- ↑ Marek, Václav (1977). Greek and Latin Inscriptions on Stone in the Collections of Charles University. Univerzita Karlova. p. 61.

- ↑ The Journal of Roman Studies. Vol. 31–32. Kraus Reprint. 1967. p. 86.

- ↑ Jens-Uwe Krause, "Children in the Roman Family and Beyond," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 627.

- ↑ Laes, Christian (2018). Disabilities and the Disabled in the Roman World: A Social and Cultural History. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9781107162907.