Related Research Articles

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other social divisions such as in race, class, and sexual orientation. The ideology and movement emerged in the 1960s.

Triple oppression, also called double jeopardy, Jane Crow, or triple exploitation, is a theory developed by black socialists in the United States, such as Claudia Jones. The theory states that a connection exists between various types of oppression, specifically classism, racism, and sexism. It hypothesizes that all three types of oppression need to be overcome at once.

Anarchist feminism is a system of analysis which combines the principles and power analysis of anarchist theory with feminism. It closely resembles intersectional feminism. Anarcha-feminism generally posits that patriarchy and traditional gender roles as manifestations of involuntary coercive hierarchy should be replaced by decentralized free association. Anarcha-feminists believe that the struggle against patriarchy is an essential part of class conflict and the anarchist struggle against the state and capitalism. In essence, the philosophy sees anarchist struggle as a necessary component of feminist struggle and vice versa. L. Susan Brown claims that "as anarchism is a political philosophy that opposes all relationships of power, it is inherently feminist".

Identity politics is politics based on a particular identity, such as race, nationality, religion, gender, sexual orientation, social background, social class. Depending on which definition of identity politics is assumed, the term could also encompass other social phenomena which are not commonly understood as exemplifying identity politics, such as governmental migration policy that regulates mobility based on identities, or far-right nationalist agendas of exclusion of national or ethnic others. For this reason, Kurzwelly, Pérez and Spiegel, who discuss several possible definitions of the term, argue that it is an analytically imprecise concept.

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation can only be achieved by dismantling the capitalist systems in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated. Marxist feminists extend traditional Marxist analysis by applying it to unpaid domestic labor and sex relations.

Socialist feminism rose in the 1960s and 1970s as an offshoot of the feminist movement and New Left that focuses upon the interconnectivity of the patriarchy and capitalism. However, the ways in which women's private, domestic, and public roles in society has been conceptualized, or thought about, can be traced back to Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and William Thompson's utopian socialist work in the 1800s. Ideas about overcoming the patriarchy by coming together in female groups to talk about personal problems stem from Carol Hanisch. This was done in an essay in 1969 which later coined the term 'the personal is political.' This was also the time that second wave feminism started to surface which is really when socialist feminism kicked off. Socialist feminists argue that liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.

Evelyn Reed was an American communist and women's rights activist.

Black feminism, also known as Afro-feminism chiefly outside the United States, is a branch of feminism that centers around black women.

The Chicago Women's Liberation Union (CWLU) was an American feminist organization founded in 1969 at a conference in Palatine, Illinois.

Frances M. Beal, also known as Fran Beal, is a Black feminist and a peace and justice political activist. Her focus has predominantly been regarding women's rights, racial justice, anti-war and peace work, as well as international solidarity. Beal was a founding member of the SNCC Black Women's Liberation Committee, which later evolved into the Third World Women's Alliance. She is most widely known for her publication, “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female", which theorizes the intersection of oppression between race, class, and gender. Beal currently lives in Oakland, California.

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) ( kəm-BEE) was a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization active in Boston, Massachusetts from 1974 to 1980. The Collective argued that both the white feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement were not addressing their particular needs as Black women and more specifically as Black lesbians. Racism was present in the mainstream feminist movement, while Delaney and Manditch-Prottas argue that much of the Civil Rights Movement had a sexist and homophobic reputation.

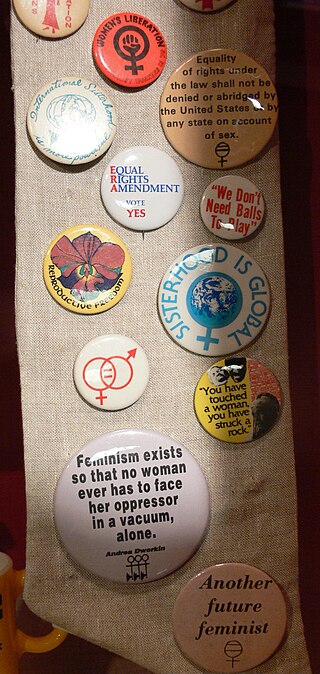

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

The Third World Women's Alliance (TWWA) was a revolutionary socialist organization for women of color active in the United States from 1968 to 1980. It aimed at ending capitalism, racism, imperialism, and sexism and was one of the earliest groups advocating for an intersectional approach to women's oppression. Members of the TWWA argued that women of color faced a "triple jeopardy" of race, gender, and class oppression. The TWWA worked to address these intersectional issues, internationally and domestically, specifically focusing much of their efforts in Cuba. Though the organization's roots lay in the black civil rights movement, it soon broadened its focus to include women of color in the US and developing nations.

Lise Vogel is a feminist sociologist and art historian from the United States. An influential Marxist-feminist theoretician, she is recognised for being one of the main founders of the Social Reproduction Theory. She also participated in the civil rights and the women's liberation movements in organisations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi and Bread & Roses in Boston. In her earlier career as an art historian, she was one of the first to try to develop a feminist perspective on Art History.

Multiple jeopardy is the theory that the various factors of one's identity that lead to discrimination or oppression, such as gender, class, or race, have a multiplicative effect on the discrimination that person experiences. The term was coined by Dr. Deborah K. King in 1988 to account for the limitations of the double or triple jeopardy models of discrimination, which assert that every unique prejudice has an individual effect on one's status, and that the discrimination one experiences is the additive result of all of these prejudices. Under the model of multiple jeopardy, it is instead believed that these prejudices are interdependent and have a multiplicative relationship; for this reason, the "multiple" in its name refers not only to the various forms of prejudices that factor into one's discrimination but also to the relationship between these prejudices. King used the term in relation to multiple consciousness, or the ability of a victim of multiple forms of discrimination to perceive how those forms work together, to support the validity of the black feminist and other intersectional causes.

Multiracial feminist theory is promoted by women of color, including Black, Latina, Asian, Native American, and anti-racist white women. In 1996, Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill wrote “Theorizing Difference from Multiracial Feminism," a piece emphasizing intersectionality and the application of intersectional analysis in feminist discourse.

The Women's liberation movement in North America was part of the feminist movement in the late 1960s and through the 1980s. Derived from the civil rights movement, student movement and anti-war movements, the Women's Liberation Movement took rhetoric from the civil rights idea of liberating victims of discrimination from oppression. They were not interested in reforming existing social structures, but instead were focused on changing the perceptions of women's place in society and the family and women's autonomy. Rejecting hierarchical structure, most groups which formed operated as collectives where all women could participate equally. Typically, groups associated with the Women's Liberation Movement held consciousness-raising meetings where women could voice their concerns and experiences, learning to politicize their issues. To members of the WLM rejecting sexism was the most important objective in eliminating women's status as second-class citizens.

Red Star was a communist publication created by the Red Women's Detachment, consisting of six issues released between March 1970 and October 1971. Articles in Red Star advocate for communist revolution to bring about women's liberation and focus on themes of violent revolution, welfare, and birth control. The Red Women's Detachment differs from traditional women's groups in its working class demographics and its revolutionary ideals, and is critical of the Women's Liberation Movement.

Women, Race and Class is a 1981 book by the American academic and author Angela Davis. It contains Marxist feminist analysis of gender, race and class. The third book written by Davis, it covers U.S. history from the slave trade and abolitionism movements to the women's liberation movements which began in the 1960s.

Feminism and racism are highly intertwined concepts in intersectional theory, focusing on the ways in which women of color in the Western World experience both sexism and racism.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sisterhood is powerful : an anthology of writings from the women's liberation movement (Book, 1970). [WorldCat.org]. OCLC 96157.

- ↑ "Frances M. Beal, Black Women's Manifesto; Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female". Hartford-hwp.com. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ↑ [BEAL, FRANCES M. “SLAVE OF A SLAVE NO MORE: BLACK WOMEN IN STRUGGLE.” The Black Scholar 6, no. 6 (1975): 2–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41065823.]>

- ↑ [Beal, Frances M. “THE MAKING OF A BLACK PRESIDENT.” The Black Scholar 15, no. 4 (1984). http://www.jstor.org/stable/41067088.]

- 1 2 3 King, Deborah K. (October 1988). "Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 14 (1): 42–72. doi:10.1086/494491. ISSN 0097-9740. S2CID 143446946.

- 1 2 3 Benita, Roth (2003). "Second Wave Black Feminism in the African Diaspora: News from New Scholarship". Agenda Feminist Media: 46–58.

- ↑ "Black Women's Activism: 2006". The Black Scholar. 36. Spring 2006. ProQuest 229767911.

- ↑ Taylor, Ula (November 1998). "The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis". Journal of Black Studies. 29 (2): 234–253. doi:10.1177/002193479802900206. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144636119.

- ↑ (EDT), Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta (2017). HOW WE GET FREE : Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Consortium Book Sales & Dist. ISBN 9781608468553. OCLC 1014297168.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Hunter, Charlayne (1970). "Many Blacks Wary of 'Women's Liberation' Movement in the U.S.". New York Times.

- 1 2 Jordan, June (1979). "To Be Black and Female". New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2018.