Blacksburg is an incorporated town in Montgomery County, Virginia, United States, with a population of 44,826 at the 2020 census. Blacksburg and the surrounding county is dominated economically and demographically by the presence of Virginia Tech.

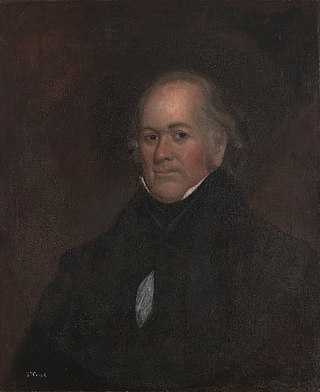

James Patton Preston was a U.S. political figure who served as the 20th Governor of Virginia.

Mary Draper Ingles, also known in records as Mary Inglis or Mary English, was an American pioneer and early settler of western Virginia. In the summer of 1755, she and her two young sons were among several captives taken by Shawnee after the Draper's Meadow Massacre during the French and Indian War. They were taken to Lower Shawneetown at the Ohio and Scioto rivers. Ingles escaped with another woman after two and a half months and trekked 500 to 600 miles, crossing numerous rivers, creeks, and the Appalachian Mountains to return home.

Lower Shawneetown, also known as Shannoah or Sonnontio, was an 18th-century Shawnee village located within the Lower Shawneetown Archeological District, near South Portsmouth in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky. The population eventually occupied areas on both sides of the Ohio River, and along both sides of the Scioto River in what is now Scioto County, Ohio. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on 28 April 1983. It is near the Bentley site, a Madisonville Horizon settlement inhabited between 1400 CE and 1625 CE. Nearby, to the east, there are also four groups of Hopewell tradition mounds, built between 100 BCE and 500 CE, known as the Portsmouth Earthworks.

Abram Trigg was an American politician from Bedford County, Virginia. He fought with the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War and represented Virginia in the U.S. Congress from 1797 until 1809. He was a slaveholder.

The Fincastle Resolutions was a statement reportedly adopted on January 20, 1775, by fifteen elected representatives of Fincastle County, Virginia. Part of the political movement that became the American Revolution, the resolutions were addressed to Virginia's delegation at the First Continental Congress, and expressed support for Congress' resistance to the Intolerable Acts, issued in 1774 by the British Parliament.

James John Floyd (1750–1783) was an early settler of St. Matthews, Kentucky, and helped lay out Louisville. In Kentucky he served as a Colonel of the Kentucky Militia in which he participated in raids with George Rogers Clark and later became one of the first judges of Kentucky.

The Captives is a 2004 American film starring Elliot Miller, produced and directed by Jude Miller for Jude True Blue Productions. It is based on the true story of Mary Draper Ingles and her struggles during the French-Indian War. The film tells the story of Mary Draper Ingles and others in her settlement being taken captive to the Ohio Country by Shawnee Indian Warriors, and her journey home as she escaped from the tribe.

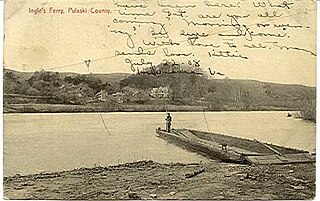

Ingles Ferry is the site of a historic ferry crossing on the New River in western Virginia, near the city of Radford in Pulaski County, Virginia, United States. A tavern was opened there in 1772 and the ferry served soldiers and civilians until 1948. A bridge was built at the site in 1842 but was burned during the civil war. The tavern and replicas of the 18th-century home of the Ingles family can be seen nearby.

Smithfield is a plantation house in Blacksburg, Virginia, built from 1772 to 1774 by Col. William Preston to be his residence and the headquarters of his farm. It was the birthplace of two Virginia Governors: James Patton Preston and John B. Floyd. The house remained a family home until 1959 when the home was donated to the APVA.

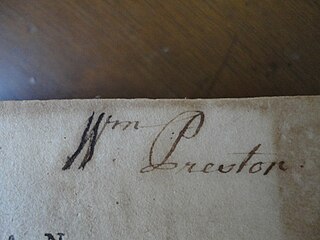

Colonel William Preston was an Irish-born American military officer, planter and politician. He played a crucial role in surveying and developing the Southern Colonies, exerted great influence in the colonial affairs of his time, owned numerous slaves on his plantation, and founded a dynasty whose progeny would supply leaders of the South for nearly a century. He served in the House of Burgesses and was a colonel in the Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War. He was one of the fifteen signatories of the Fincastle Resolutions. Preston was also a founding trustee of Liberty Hall when it was transformed into a college in 1776.

Fort Vause was built in 1753 in Montgomery County, Virginia, by Ephraim Vause. The historic site is near the town of Shawsville, Virginia. It was attacked by French troops and Native American warriors in 1756, and most of the inhabitants were killed or taken prisoner. The fort was rebuilt in 1757 but abandoned by 1759.

Follow the River is a 1995 ABC television movie based on the book Follow the River by James Alexander Thom that told the story of the aftermath of the Draper's Meadow Massacre of 1755.

Samuel Stalnaker was an explorer, trapper, guide and one of the first settlers on the Virginia frontier. He established a trading post, hotel and tavern in 1752 near what is now Chilhowie, Virginia. He was held captive by Shawnee Indians at Lower Shawneetown in Kentucky for almost a year, before escaping and traveling over 460 miles to Williamsburg, Virginia, to report on French preparations to attack English settlements in Virginia and Pennsylvania. He later served as a guide under George Washington during the French and Indian War.

The Sandy Creek Expedition, also known as the Sandy Expedition or the Big Sandy Expedition, was a 1756 campaign by Virginia Regiment soldiers and Cherokee warriors into modern-day West Virginia against the Shawnee, who were raiding the British colony of Virginia's frontier. The campaign set out in mid-February, 1756, and was immediately slowed by harsh weather and inadequate provisions. With morale failing, the expedition was forced to turn back in mid-March without encountering the enemy.

William Ingles, also spelled Inglis, Ingliss, Engels, or English, was a colonist and soldier in colonial Virginia. He participated in the Sandy Creek Expedition and was a signatory of the Fincastle Resolutions. He was eventually promoted to colonel in the Virginia Regiment. His wife, Mary Draper Ingles, was captured by Shawnee warriors and held captive for months before escaping and walking several hundred miles to her settlement. William's sons, Thomas and George, were also held captive, although William was able to ransom his son Thomas in 1768. William Ingles established Ingles Ferry in southwestern Virginia.

Thomas Ingles was a Virginia pioneer, frontiersman and soldier. He was the son of William Ingles and Mary Draper Ingles. He, his mother and his younger brother were captured by Shawnee Indians and although his mother escaped, Thomas remained with the Shawnee until age 17, when his father paid a ransom and brought him back to Virginia. He later served in the Virginia militia, reaching the rank of colonel by 1780.

James Lynn Patton, was a merchant, pioneer frontiersman, and soldier who settled parts of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. Between his immigration to Virginia in 1740, and his death there in 1755, he was a prominent figure in the exploration, settlement, governance, and military leadership of the colony. Patton held such Augusta County offices as Justice of the Peace, Colonel of Militia and Chief Commander of the Augusta County Militia, County Lieutenant, President of the Augusta Court, commissioner of the Tinkling Spring congregation, county coroner, county escheator, collector of duties on furs and skins, and County Sheriff. He also was President of the Augusta Parish Vestry and a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. He was present at three important treaty conferences with Iroquois and Cherokee leaders. Patton was killed by Shawnee warriors in July 1755.

The Battle of Galudoghson took place in December 1742, at a site near present-day Glasgow, Virginia, when the Augusta County militia engaged in combat with Onondaga and Oneida Indians. These warriors had traveled to Virginia from Pennsylvania under the command of an Iroquois chief named Jonnhaty, to participate in a campaign against the Catawba. The battle was the first armed conflict between settlers in Western Virginia and Native Americans. Several distinct accounts of the battle exist, with contradictory details. The Iroquois regarded the battle as an unprovoked act of aggression, while the Virginia colonists claimed that the Iroquois had raided Virginia settlements and killed livestock. The battle was one factor that led colonial authorities to negotiate with Native American leaders for the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster.

John Buchanan was a colonial Virginia landowner, magistrate, colonel in the Virginia Militia, deputy surveyor under Thomas Lewis, and Sheriff of Augusta County, Virginia. As a surveyor, Buchanan was able to locate and purchase some of the most desirable plots of land in western Virginia and quickly became wealthy and politically influential. As magistrate, sheriff and a colonel the Augusta County Militia, he was already well-connected when his father-in-law Colonel James Patton was killed in 1755. Buchanan had replaced Patton in several key roles by the time of his own death in 1769.