The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. The denomination holds the New Testament as its only creed. Historically, the church has taken a strong stance for nonresistance or Christian pacifism—it is one of the three historic peace churches, alongside the Mennonites and Quakers. Distinctive practices include believer's baptism by forward trine immersion; a threefold love feast consisting of feet washing, a fellowship meal, and communion; anointing for healing; and the holy kiss. Its headquarters are in Elgin, Illinois, United States.

Ephrata is a borough in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located 42 miles (68 km) east of Harrisburg and about 60 miles (97 km) west-northwest of Philadelphia and is named after Ephrath, the former name for current-day Bethlehem. In its early history, Ephrata was a pleasure resort and an agricultural community.

The Old German Baptist Brethren (OGBB) is a Schwarzenau Brethren denomination of Anabaptist Christianity.

The Schwarzenau Brethren, the German Baptist Brethren, Dunkers, Dunkard Brethren, Tunkers, or sometimes simply called the German Baptists, are an Anabaptist group that dissented from Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed European state churches during the 17th and 18th centuries. German Baptist Brethren emerged in some German-speaking states in western and southwestern parts of the Holy Roman Empire as a result of the Radical Pietist revival movement of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, where people began to read and study their Bibles on their own- rather than just being told what to believe and do.

The Ephrata Cloister or Ephrata Community was a religious community, established in 1732 by Johann Conrad Beissel at Ephrata, in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The grounds of the community are now owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and are administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

The Brethren Church is an Anabaptist Christian denomination with roots in and one of several groups that trace its origins back to the Schwarzenau Brethren of Germany, and is a member of the National Association of Evangelicals.

The Dunkard Brethren Church is a Conservative Anabaptist denomination of the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition, which organized in 1926 when they withdrew from the Church of the Brethren in the United States.

Johann Conrad Beissel was a German-born religious leader who in 1732 founded the Ephrata Community in the Province of Pennsylvania.

Conestoga originally referred to the Conestoga people, an English name for the Susquehannock people of Pennsylvania.

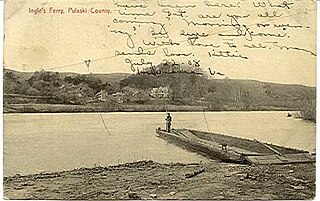

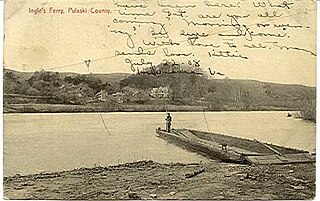

Claytor Lake in Pulaski County, Virginia, is a 4,472-acre (1,810 ha), 21-mile-long (34 km) reservoir on the New River, created for an Appalachian Power Company hydroelectric project. It is named for W. Graham Claytor, Sr. (1886–1971) of Roanoke, Virginia, a vice president of Appalachian Power who had supervised the construction of the Claytor Dam, which created the lake.

The Community of True Inspiration, also known as the True Inspiration Congregations, Inspirationalists, and the Amana Church Society) is a Radical Pietist group of Christians descending from settlers of German, Swiss, and Austrian descent who settled in West Seneca, New York, after purchasing land from the Seneca peoples' Buffalo Creek Reservation. They were from a number of backgrounds and socioeconomic areas and later moved to Amana, Iowa when they became dissatisfied with the congestion of Erie County and the growth of Buffalo, New York. Christian worship in the Community of True Inspiration continues, largely unchanged from its inception.

Radical Pietism are those Christian churches who decided to break with denominational Lutheranism in order to emphasize certain teachings regarding holy living. Radical Pietists contrast with Church Pietists, who chose to remain within their Lutheran denominational settings. Radical Pietists distinguish between true and false Christianity and hold that the latter is represented by established churches. They separated from established churches to form their own Christian denominations.

Marie Elizabeth Kachel Bucher was an American school-teacher and the last surviving resident member of the German Seventh-Day Baptists religious congregation of the Ephrata Cloister, a United States National Historic Landmark located in Ephrata, Pennsylvania.

Christoph Sauer was the first German-language printer and publisher in North America.

Ingles Ferry is the site of a historic ferry crossing on the New River in western Virginia, near the city of Radford in Pulaski County, Virginia, United States. A tavern was opened there in 1772 and the ferry served soldiers and civilians until 1948. A bridge was built at the site in 1842 but was burned during the civil war. The tavern and replicas of the 18th-century home of the Ingles family can be seen nearby.

Oregon is an unincorporated community that is located in Manheim Township, Lancaster County, in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is situated near the intersection of PA 722 and the Oregon Pike, between Lancaster and Ephrata.

Julius Friedrich (Frederick) Adolph Sachse was an American scholar of the history of Pennsylvania, particularly of the Ephrata Cloister and sectarian Pennsylvania German groups, as well as of American Freemasonry, and photographer. He was born in Philadelphia and graduated from Muhlenberg College. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1894. He was editor of the American Journal of Photography from 1890 to 1897. Although raised a Lutheran, Sachse's children were baptized in the German Reformed Church, and he attended Episcopal churches in Philadelphia from about 1895 until his death.

William Ingles, also spelled Inglis, Ingliss, Engels, or English, was a colonist and soldier in colonial Virginia. He participated in the Sandy Creek Expedition and was a signatory of the Fincastle Resolutions. He was eventually promoted to colonel in the Virginia Regiment. His wife, Mary Draper Ingles, was captured by Shawnee warriors and held captive for months before escaping and walking several hundred miles to her settlement. William's sons, Thomas and George, were also held captive, although William was able to ransom his son Thomas in 1768. William Ingles established Ingles Ferry in southwestern Virginia.

Dunkard Bottom was a Schwarzenau Brethren religious community established on the Cheat River in 1753 by brothers Samuel, Gabriel and Israel Eckerlin. It flourished for only a few years until it was destroyed by Native Americans in 1757.