The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against Sweden and the United States over disputes regarding tributary payments made by both states in exchange for a cessation of Tripolitatian commerce raiding at sea. United States President Thomas Jefferson refused to pay this tribute. Sweden had been at war with the Tripolitans since 1800.

The Barbary Wars were a series of two wars fought by the United States, Sweden, and the Kingdom of Sicily against the Barbary states and Morocco of North Africa in the early 19th century. Sweden had been at war with the Tripolitans since 1800 and was joined by the newly independent US. The First Barbary War extended from 10 May 1801 to 10 June 1805, with the Second Barbary War lasting only three days, ending on 19 June 1815.

The Second Barbary War (1815) or the U.S.–Algerian War was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen Decatur's Algerian treaty on 5 December 1815. However, Dey Omar Agha of Algeria repudiated the US treaty, refused to accept the terms of peace that had been ratified by the Congress of Vienna, and threatened the lives of all Christian inhabitants of Algiers. William Shaler was the US commissioner in Algiers who had negotiated alongside Decatur, but he fled aboard British vessels during the 1816 bombardment of Algiers. He negotiated a new treaty in 1816 which was not ratified by the Senate until 11 February 1822, because of an oversight.

The Treaty of Tripoli was signed in 1796. It was the first treaty between the United States and Tripoli to secure commercial shipping rights and protect American ships in the Mediterranean Sea from local Barbary pirates.

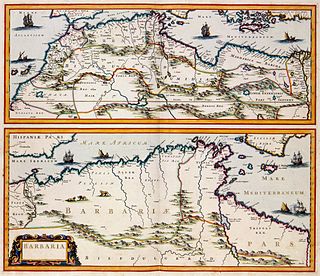

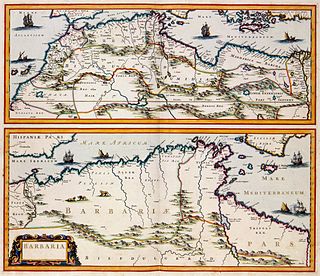

The Barbary Coast was the name given to the coastal regions of central and western North Africa or more specifically the Maghreb, specifically the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, as well as the Sultanate of Morocco from the 16th to 19th centuries. The term originates from the exonym of the Berbers.

The Barbary pirates, Barbary corsairs, or Ottoman corsairs were mainly Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from the Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, in reference to the Berbers. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture slaves for the Barbary slave trade. Slaves in Barbary could be of many ethnicities, and of many different religions, such as Christian, Jewish, or Muslim. Their predation extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland, but they primarily operated in the western Mediterranean. In addition to seizing merchant ships, they engaged in razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, the Netherlands, and Iceland.

The Bombardment of Algiers was an attempt on 27 August 1816 by Britain and the Netherlands to end the slavery practices of Omar Agha, the Dey of Algiers. An Anglo-Dutch fleet under the command of Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth bombarded ships and the harbour defences of Algiers.

The Regency of Algiers was an autonomous eyalet of the Ottoman Empire in what was known as the Barbary coast of North Africa from 1516 to 1830. It was an early modern tributary state founded by the corsair brothers Oruç and Hayreddin Barbarossa, ruled first by viceroys, which later became a sovereign military republic. The Regency was infamous for its Barbary corsairs, making it a formidable pirate base for maritime Holy war and plunder against Christian powers. It was also the strongest Barbary state. Situated between the Regency of Tunis in the east, the Sharifian Sultanate of Morocco and Spanish Oran in the west, the Regency originally extended its borders from the Mellegue river in the east to Moulouya river in the west and from Collo to Ouargla, with nominal authority over the Tuat and In Salah to the south. At the end of the Regency, it extended to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.

Lambert Hendriksz was a Dutch vice admiral. He is usually referred to by his nickname, Mooy Lambert. Lambert served under Willem de Zoete and Jacob van Heemskerk, and was present as a rear admiral at the battle of Gibraltar. Lambert was active against the Dunkirk corsairs and in 1605 managed to defeat and capture the Dunkirk admiral Adriaan Dirksen.

Jan Janszoon van Haarlem, commonly known as Reis Mourad the Younger, was a former Dutch pirate who became a Barbary corsair in Ottoman Algeria and the Republic of Salé. After being captured by Algerian corsairs off Lanzarote in 1618, he converted to Islam and changed his name to Mourad. He became one of the most famous of the 17th-century Barbary corsairs. Together with other corsairs, he helped establish the independent Republic of Salé at the city of that name, serving as the first President and Commander. He also served as Governor of Oualidia.

The Barbary slave trade involved the capture and selling of European slaves at slave markets in the Barbary states. European slaves were captured by Muslim Barbary pirates in slave raids on ships and by raids on coastal towns from Italy to the Netherlands, Ireland and the southwest of Britain, as far north as Iceland and into the Eastern Mediterranean.

Siemen Danziger, better known by his anglicized names Zymen Danseker and Simon de Danser, was a 17th-century Dutch privateer and Barbary corsair based in Ottoman Algeria. His name is also written Danziker, Dansker, Dansa or Danser.

Anglo-Turkish piracy or the Anglo-Barbary piracy was the collaboration between Barbary pirates and English pirates against Catholic shipping during the 17th century.

Slavery on the Barbary Coast refer to the enslavement of people taken captive by the barbary corsairs in the Barbary Coast area of North Africa.

The invasion of Algiers was a massive and disastrous amphibious attempt in July 1775 by a combined Spanish and Tuscan force to capture the city of Algiers, the capital of The Deylik of Algeria. The amphibious assault was led by Spanish general Alexander O'Reilly and Tuscan admiral Sir John Acton, commanding a total of 20,000 men along with 74 warships of various sizes and 230 transport ships carrying the troops for the invasion. The defending Algerian forces were led by Baba Mohammed ben-Osman. The assault was ordered by the King of Spain, Charles III, who was attempting to demonstrate to the Barbary States the power of the revitalized Spanish military after the disastrous Spanish experience in the Seven Years' War. The assault was also meant to demonstrate that Spain would defend its North African exclaves against any Ottoman or Moroccan encroachment, and reduce the influence that the Barbary states held in the Mediterranean.

The French-Algerian War of 1681–1688 was part of a wider campaign by France against the Barbary Pirates in the 1680s.

Slavery is noted in the area later known as Algeria since antiquity. Algeria was a center of the Trans-Saharan slave trade route of enslaved Black Africans from sub-Saharan Africa, as well as a center of the slave trade of Barbary slave trade of Europeans captured by the barbary pirates.

In 1622 The Dutch Republic and The Regency of Algiers concluded a peace treaty. The Algerians failed to respect the treaty. Following this the Dutch set out a punitive expedition to punish the Algerians.

The Dutch–Algerian War (1715–1726) denotes a conflict between the Dutch Republic and the Regency of Algiers. It commenced with initial successes for Algiers, involving the capture of numerous Dutch ships. However, as the war progressed, the Dutch managed to change the balance of naval successes. Ultimately, this, together with the eventuality of Britain, and France joining the war, and the Dutch blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar facilitated a peace treaty.

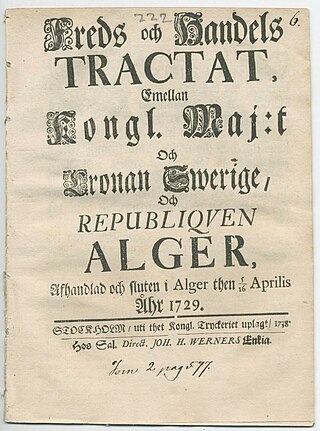

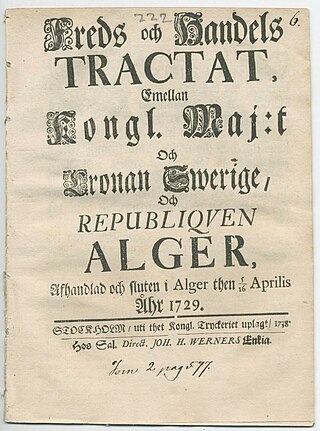

Treaty between Algiers and Sweden (1729) was the first treaty between Sweden and Regency of Algiers and acted as a peace and trade treaty, it regarded the treatment of Swedish captives in Algeria, and in return for regular tribute Swedish ships were to carry special passes and would be granted immunity from attack in the Mediterranean sea.