The cane toad, also known as the giant neotropical toad or marine toad, is a large, terrestrial true toad native to South and mainland Central America, but which has been introduced to various islands throughout Oceania and the Caribbean, as well as Northern Australia. It is a member of the genus Rhinella, which includes many true toad species found throughout Central and South America, but it was formerly assigned to the genus Bufo.

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order Anura. The oldest fossil "proto-frog" Triadobatrachus is known from the Early Triassic of Madagascar, but molecular clock dating suggests their split from other amphibians may extend further back to the Permian, 265 million years ago. Frogs are widely distributed, ranging from the tropics to subarctic regions, but the greatest concentration of species diversity is in tropical rainforest. Frogs account for around 88% of extant amphibian species. They are also one of the five most diverse vertebrate orders. Warty frog species tend to be called toads, but the distinction between frogs and toads is informal, not from taxonomy or evolutionary history.

Bufo is a genus of true toads in the amphibian family Bufonidae. As traditionally defined, it was a wastebasket genus containing a large number of toads from much of the world but following taxonomic reviews most of these have been moved to other genera, leaving only seventeen extant species from Europe, northern Africa and Asia in this genus, including the well-known common toad. Some of the genera that contain species formerly placed in Bufo are Anaxyrus, Bufotes, Duttaphrynus, Epidalea and Rhinella.

The common toad, European toad, or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the toad, is a frog found throughout most of Europe, in the western part of North Asia, and in a small portion of Northwest Africa. It is one of a group of closely related animals that are descended from a common ancestral line of toads and which form a species complex. The toad is an inconspicuous animal as it usually lies hidden during the day. It becomes active at dusk and spends the night hunting for the invertebrates on which it feeds. It moves with a slow, ungainly walk or short jumps, and has greyish-brown skin covered with wart-like lumps.

In evolutionary biology, an evolutionary arms race is an ongoing struggle between competing sets of co-evolving genes, phenotypic and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other, resembling the geopolitical concept of an arms race. These are often described as examples of positive feedback. The co-evolving gene sets may be in different species, as in an evolutionary arms race between a predator species and its prey, or a parasite and its host. Alternatively, the arms race may be between members of the same species, as in the manipulation/sales resistance model of communication or as in runaway evolution or Red Queen effects. One example of an evolutionary arms race is in sexual conflict between the sexes, often described with the term Fisherian runaway. Thierry Lodé emphasized the role of such antagonistic interactions in evolution leading to character displacements and antagonistic coevolution.

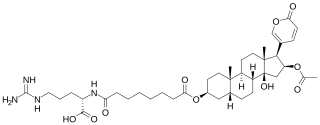

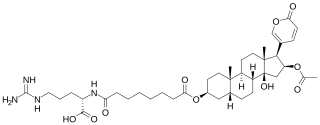

Bufotoxins are a family of toxic steroid lactones or substituted tryptamines of which some are toxic. They occur in the parotoid glands, skin, and poison of many toads and other amphibians, and in some plants and mushrooms. The exact composition varies greatly with the specific source of the toxin. It can contain 5-MeO-DMT, bufagins, bufalin, bufotalin, bufotenin, bufothionine, dehydrobufotenine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Some authors have also used the term bufotoxin to describe the conjugate of a bufagin with suberylarginine.

The American toad is a common species of toad found throughout Canada and the eastern United States. It is divided into three subspecies: the eastern American toad, the dwarf American toad and the rare Hudson Bay toad. Recent taxonomic treatments place this species in the genus Anaxyrus instead of Bufo.

The Houston toad, formerly Bufo houstonensis, is an endangered species of amphibian that is endemic to Texas in the United States. This toad was discovered in the late 1940s and named in 1953. It was among the first amphibians added to the United States List of Endangered Native Fish and Wildlife and is currently protected by the Endangered Species Act of 1973 as an endangered species. The Houston toad was placed as "endangered" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species from 1986 to 2022, and has worsened to "critically endangered" since then, with fewer than 250 mature individuals believed to remain in the wild as of 2021. Their kind is threatened every day as they continue to suffer from a loss of habitat, extreme drought, and massive wildfires. Their typical life expectancy is at least 3 years but it may exceed this number.

The banded bullfrog is a species of frog in the narrow-mouthed frog family Microhylidae. Native to Southeast Asia, it is also known as the Asian painted frog, digging frog, Malaysian bullfrog, common Asian frog, and painted balloon frog. In the pet trade, it is sometimes called the chubby frog. Adults measure 5.4 to 7.5 cm and have a dark brown back with stripes that vary from copper-brown to salmon pink.

Wolfgang Wüster is a herpetologist and Professor in Zoology at Bangor University, UK.

Duttaphrynus stomaticus, also known as the Indian marbled toad, Punjab toad, Indus Valley toad, or marbled toad, is a species of toad found in Asia from eastern Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan to Nepal, extending into Peninsular India and Bangladesh.

Duttaphrynus, named after Sushil Kumar Dutta, is a genus of true toads endemic to southwestern and southern China, Taiwan and throughout southern Asia from northern Pakistan and Nepal through India and Bangladesh to Sri Lanka, Andaman Island, Sumatra, Java, Borneo and Bali.

The New Guinean quoll, also known as the New Guinea quoll or New Guinea native cat, is a carnivorous marsupial mammal native to New Guinea. It is the second-largest surviving marsupial carnivore of New Guinea. It is known as suatg in the Kalam language of Papua New Guinea.

The oak toad is a species of toad in the family Bufonidae. It is endemic to the coastal regions of southeastern United States. It is regarded as the smallest species of toad in North America, with a length of 19 to 33 mm.

The cane toad in Australia is regarded as an exemplary case of an invasive species. Australia's relative isolation prior to European colonisation and the industrial revolution, both of which dramatically increased traffic and import of novel species, allowed development of a complex, interdepending system of ecology, but one which provided no natural predators for many of the species subsequently introduced. The recent, sudden inundation of foreign species has led to severe breakdowns in Australian ecology, after overwhelming proliferation of a number of introduced species, for which the continent has no efficient natural predators or parasites, and which displace native species; in some cases, these species are physically destructive to habitat, as well. Cane toads have been very successful as an invasive species, having become established in more than 15 countries within the past 150 years. In the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, the Australian government listed the impacts of the cane toad as a "key threatening process".

Mitchell's water monitor is a semiaquatic species of monitor lizard in the family Varanidae. The species is native to Australia. The species is native to the Northern regions of Australia, and is on IUCN's Red List as a critically endangered species. They can be distinguished by the orange or yellow stripes along their neck and dark spots along their back. They are mainly carnivorous, and eat small prey such as lizard, birds, and insects.

Richard Shine is an Australian evolutionary biologist and ecologist; he has conducted extensive research on reptiles and amphibians, and proposed a novel mechanism for evolutionary change. He is currently a Professor of Biology at Macquarie University, and an Emeritus Professor at The University of Sydney.

Native to both South and Central America, Cane toads were introduced to Australia in the 1930s and have since become an invasive species and a threat to the continent's native predators and scavengers.

Oligodon fasciolatus, commonly known as the small-banded kukri snake or the fasciolated kukri snake, is a species of snake in the family Colubridae. The species is native to Southeast Asia. This snake uniquely eviscerates live poisonous toads, Duttaphrynus melanostictus, to avoid toxic white liquid the toad secretes.