The Concordat of Worms, also referred to as the Pactum Callixtinum or Pactum Calixtinum, was an agreement between the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire which regulated the procedure for the appointment of bishops and abbots in the Empire. Signed on 23 September 1122 in the German city of Worms by Pope Callixtus II and Emperor Henry V, the agreement set an end to the Investiture Controversy, a conflict between state and church over the right to appoint religious office holders that had begun in the middle of the 11th century.

Pope Honorius II, born Lamberto Scannabecchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 December 1124 to his death in 1130.

The Salian dynasty or Salic dynasty was a dynasty in the High Middle Ages. The dynasty provided four kings of Germany (1024–1125), all of whom went on to be crowned Holy Roman emperors (1027–1125).

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon rather than in Rome. The situation arose from the conflict between the papacy and the French crown, culminating in the death of Pope Boniface VIII after his arrest and maltreatment by Philip IV of France. Following the subsequent death of Pope Benedict XI, Philip pressured a deadlocked conclave to elect the Archbishop of Bordeaux as pope Clement V in 1305. Clement refused to move to Rome, and in 1309 he moved his court to the papal enclave at Avignon, where it remained for the next 67 years. This absence from Rome is sometimes referred to as the "Babylonian captivity" of the Papacy.

Pope Lucius II, born Gherardo Caccianemici dal Orso, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1144 to his death in 1145. His pontificate was notable for the unrest in Rome associated with the Commune of Rome and its attempts to wrest control of the city from the papacy. He supported Empress Matilda's claim to England in the Anarchy, and had a tense relationship with King Roger II of Sicily.

A prince-bishop is a bishop who is also the civil ruler of some secular principality and sovereignty, as opposed to Prince of the Church itself, a title associated with cardinals. Since 1951, the sole extant prince-bishop has been the Bishop of Urgell, Catalonia, who has remained ex officio one of two co-princes of Andorra, along with the French president.

The Holy See exercised sovereign and secular power, as distinguished from its spiritual and pastoral activity, while the pope ruled the Papal States in central Italy.

Ralph d'Escures was a medieval abbot of Séez, bishop of Rochester, and then archbishop of Canterbury. He studied at the school at the Abbey of Bec. In 1079 he entered the abbey of St Martin at Séez and became abbot there in 1091. He was a friend of both Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury and Bishop Gundulf of Rochester, whose see, or bishopric, he took over on Gundulf's death.

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monasteries and the pope himself. A series of popes in the 11th and 12th centuries undercut the power of the Holy Roman Emperor and other European monarchies, and the controversy led to nearly 50 years of conflict.

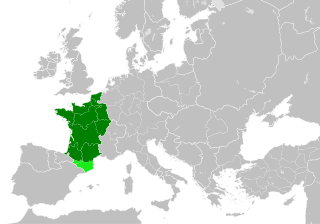

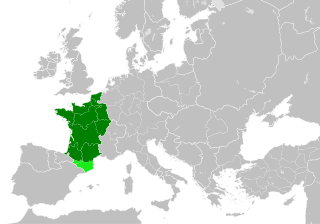

The Kingdom of France in the Middle Ages was marked by the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and West Francia (843–987); the expansion of royal control by the House of Capet (987–1328), including their struggles with the virtually independent principalities, and the creation and extension of administrative/state control in the 13th century; and the rise of the House of Valois (1328–1589), including the protracted dynastic crisis against the House of Plantagenet and their Angevin Empire, culminating in the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), which laid the seeds for a more centralized and expanded state in the early modern period and the creation of a sense of French identity.

The Prussian Homage or Prussian Tribute was the formal investiture of Albert, Duke of Prussia (1490-1568), with his Duchy of Prussia as a fief of the Kingdom of Poland that took place on 10 April 1525 in the then capital of Kraków, Kingdom of Poland. This ended the rule of the Teutonic Order in Prussia, which became a secular Protestant state.

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be named after Pope Gregory VII (1073–85), though he personally denied it and claimed his reforms, like his regnal name, honoured Pope Gregory I.

Alfonso, also called Anfuso or Anfusus (c. 1120 – 10 October 1144), was the Prince of Capua from 1135 and Duke of Naples from 1139. He was an Italian-born Norman of the noble Hauteville family. After 1130, when his father Roger became King of Sicily, he was the third in line to the throne; second in line after the death of an older brother in 1138. He was the first Hauteville prince of Capua after his father conquered the principality from the rival Norman Drengot family. He was also the first Norman duke of Naples after the duchy fell vacant on the death of the last Greek duke. He also expanded his family's power northwards, claiming lands also claimed by the Papacy, although he was technically a vassal of the Pope for his principality of Capua.

The Kingdom of Italy, also called Imperial Italy, was one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, along with the kingdoms of Germany, Bohemia, and Burgundy. It originally comprised large parts of northern and central Italy. Its original capital was Pavia until the 11th century.

The Livonian crusade consists of the various military Christianisation campaigns in medieval Livonia – modern Latvia and Estonia – during the Papal-sanctioned Northern Crusades in the 12th–13th century.

Christianity in the 11th century is marked primarily by the Great Schism of the Church, which formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches.

The history of the papacy from 1046 to 1216 was marked by conflict between popes and the Holy Roman Emperor, most prominently the Investiture Controversy, a dispute over who— pope or emperor— could appoint bishops within the Empire. Henry IV's Walk to Canossa in 1077 to meet Pope Gregory VII (1073–85), although not dispositive within the context of the larger dispute, has become legendary. Although the emperor renounced any right to lay investiture in the Concordat of Worms (1122), the issue would flare up again.

Feudalism in the Holy Roman Empire was a politico-economic system of relationships between liege lords and enfeoffed vassals that formed the basis of the social structure within the Holy Roman Empire during the High Middle Ages. In Germany the system is variously referred to Lehnswesen, Feudalwesen or Benefizialwesen.

Terra Mariana was the formal name for Medieval Livonia or Old Livonia. It was formed in the aftermath of the Livonian Crusade, and its territories were composed of present-day Estonia and Latvia. It was established on 2 February 1207, as a principality of the Holy Roman Empire, and lost this status in 1215 when Pope Innocent III proclaimed it as directly subject to the Holy See.

The papal nobility are the aristocracy of the Holy See, composed of persons holding titles bestowed by the Pope. From the Middle Ages into the nineteenth century, the papacy held direct temporal power in the Papal States, and many titles of papal nobility were derived from fiefs with territorial privileges attached. During this time, the Pope also bestowed ancient civic titles such as patrician. Today, the Pope still exercises authority to grant titles with territorial designations, although these are purely nominal and the privileges enjoyed by the holders pertain to styles of address and heraldry. Additionally, the Pope grants personal and familial titles that carry no territorial designation. Their titles being merely honorific, the modern papal nobility includes descendants of ancient Roman families as well as notable Catholics from many countries. All pontifical noble titles are within the personal gift of the pontiff, and are not recorded in the Official Acts of the Holy See.