In chemistry, an acid dissociation constant is a quantitative measure of the strength of an acid in solution. It is the equilibrium constant for a chemical reaction

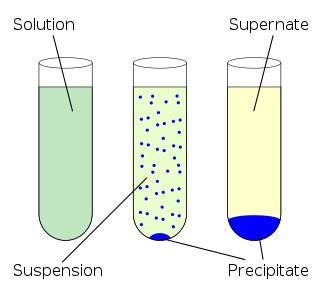

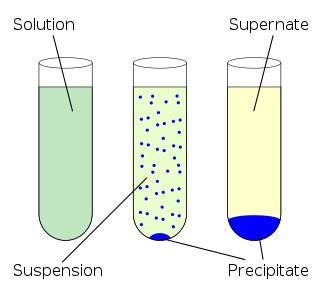

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

Solubility equilibrium is a type of dynamic equilibrium that exists when a chemical compound in the solid state is in chemical equilibrium with a solution of that compound. The solid may dissolve unchanged, with dissociation, or with chemical reaction with another constituent of the solution, such as acid or alkali. Each solubility equilibrium is characterized by a temperature-dependent solubility product which functions like an equilibrium constant. Solubility equilibria are important in pharmaceutical, environmental and many other scenarios.

The reaction rate or rate of reaction is the speed at which a chemical reaction takes place, defined as proportional to the increase in the concentration of a product per unit time and to the decrease in the concentration of a reactant per unit time. Reaction rates can vary dramatically. For example, the oxidative rusting of iron under Earth's atmosphere is a slow reaction that can take many years, but the combustion of cellulose in a fire is a reaction that takes place in fractions of a second. For most reactions, the rate decreases as the reaction proceeds. A reaction's rate can be determined by measuring the changes in concentration over time.

Chemical kinetics, also known as reaction kinetics, is the branch of physical chemistry that is concerned with understanding the rates of chemical reactions. It is different from chemical thermodynamics, which deals with the direction in which a reaction occurs but in itself tells nothing about its rate. Chemical kinetics includes investigations of how experimental conditions influence the speed of a chemical reaction and yield information about the reaction's mechanism and transition states, as well as the construction of mathematical models that also can describe the characteristics of a chemical reaction.

In chemistry, intramolecular describes a process or characteristic limited within the structure of a single molecule, a property or phenomenon limited to the extent of a single molecule.

In chemistry, reactivity is the impulse for which a chemical substance undergoes a chemical reaction, either by itself or with other materials, with an overall release of energy.

In physical organic chemistry, a kinetic isotope effect (KIE) is the change in the reaction rate of a chemical reaction when one of the atoms in the reactants is replaced by one of its isotopes. Formally, it is the ratio of rate constants for the reactions involving the light (kL) and the heavy (kH) isotopically substituted reactants (isotopologues):

The equilibrium constant of a chemical reaction is the value of its reaction quotient at chemical equilibrium, a state approached by a dynamic chemical system after sufficient time has elapsed at which its composition has no measurable tendency towards further change. For a given set of reaction conditions, the equilibrium constant is independent of the initial analytical concentrations of the reactant and product species in the mixture. Thus, given the initial composition of a system, known equilibrium constant values can be used to determine the composition of the system at equilibrium. However, reaction parameters like temperature, solvent, and ionic strength may all influence the value of the equilibrium constant.

Thermodynamic reaction control or kinetic reaction control in a chemical reaction can decide the composition in a reaction product mixture when competing pathways lead to different products and the reaction conditions influence the selectivity or stereoselectivity. The distinction is relevant when product A forms faster than product B because the activation energy for product A is lower than that for product B, yet product B is more stable. In such a case A is the kinetic product and is favoured under kinetic control and B is the thermodynamic product and is favoured under thermodynamic control.

In physical organic chemistry, a free-energy relationship or Gibbs energy relation relates the logarithm of a reaction rate constant or equilibrium constant for one series of chemical reactions with the logarithm of the rate or equilibrium constant for a related series of reactions. Free energy relationships establish the extent at which bond formation and breakage happen in the transition state of a reaction, and in combination with kinetic isotope experiments a reaction mechanism can be determined. Free energy relationships are often used to calculate equilibrium constants since they are experimentally difficult to determine.

In organic chemistry, cheletropic reactions, also known as chelotropic reactions, are a type of pericyclic reaction. Specifically, cheletropic reactions are a subclass of cycloadditions. The key distinguishing feature of cheletropic reactions is that on one of the reagents, both new bonds are being made to the same atom.

The Curtin–Hammett principle is a principle in chemical kinetics proposed by David Yarrow Curtin and Louis Plack Hammett. It states that, for a reaction that has a pair of reactive intermediates or reactants that interconvert rapidly, each going irreversibly to a different product, the product ratio will depend both on the difference in energy between the two conformers and the energy barriers from each of the rapidly equilibrating isomers to their respective products. Stated another way, the product distribution reflects the difference in energy between the two rate-limiting transition states. As a result, the product distribution will not necessarily reflect the equilibrium distribution of the two intermediates. The Curtin–Hammett principle has been invoked to explain selectivity in a variety of stereo- and regioselective reactions. The relationship between the (apparent) rate constants and equilibrium constant is known as the Winstein-Holness equation.

In chemistry, transition state theory (TST) explains the reaction rates of elementary chemical reactions. The theory assumes a special type of chemical equilibrium (quasi-equilibrium) between reactants and activated transition state complexes.

Physical organic chemistry, a term coined by Louis Hammett in 1940, refers to a discipline of organic chemistry that focuses on the relationship between chemical structures and reactivity, in particular, applying experimental tools of physical chemistry to the study of organic molecules. Specific focal points of study include the rates of organic reactions, the relative chemical stabilities of the starting materials, reactive intermediates, transition states, and products of chemical reactions, and non-covalent aspects of solvation and molecular interactions that influence chemical reactivity. Such studies provide theoretical and practical frameworks to understand how changes in structure in solution or solid-state contexts impact reaction mechanism and rate for each organic reaction of interest.

In theoretical chemistry, an energy profile is a theoretical representation of a chemical reaction or process as a single energetic pathway as the reactants are transformed into products. This pathway runs along the reaction coordinate, which is a parametric curve that follows the pathway of the reaction and indicates its progress; thus, energy profiles are also called reaction coordinate diagrams. They are derived from the corresponding potential energy surface (PES), which is used in computational chemistry to model chemical reactions by relating the energy of a molecule(s) to its structure.

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter. The others are solid, liquid, and plasma. A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms, elemental molecules made from one type of atom, or compound molecules made from a variety of atoms. A gas mixture, such as air, contains a variety of pure gases. What distinguishes gases from liquids and solids is the vast separation of the individual gas particles. This separation usually makes a colorless gas invisible to the human observer.

In chemistry, solvent effects are the influence of a solvent on chemical reactivity or molecular associations. Solvents can have an effect on solubility, stability and reaction rates and choosing the appropriate solvent allows for thermodynamic and kinetic control over a chemical reaction.

In organosulfur chemistry, the thiol-ene reaction is an organic reaction between a thiol and an alkene to form a thioether. This reaction was first reported in 1905, but it gained prominence in the late 1990s and early 2000s for its feasibility and wide range of applications. This reaction is accepted as a click chemistry reaction given the reactions' high yield, stereoselectivity, high rate, and thermodynamic driving force.

In stable isotope geochemistry, the Urey–Bigeleisen–Mayer equation, also known as the Bigeleisen–Mayer equation or the Urey model, is a model describing the approximate equilibrium isotope fractionation in an isotope exchange reaction. While the equation itself can be written in numerous forms, it is generally presented as a ratio of partition functions of the isotopic molecules involved in a given reaction. The Urey–Bigeleisen–Mayer equation is widely applied in the fields of quantum chemistry and geochemistry and is often modified or paired with other quantum chemical modelling methods to improve accuracy and precision and reduce the computational cost of calculations.